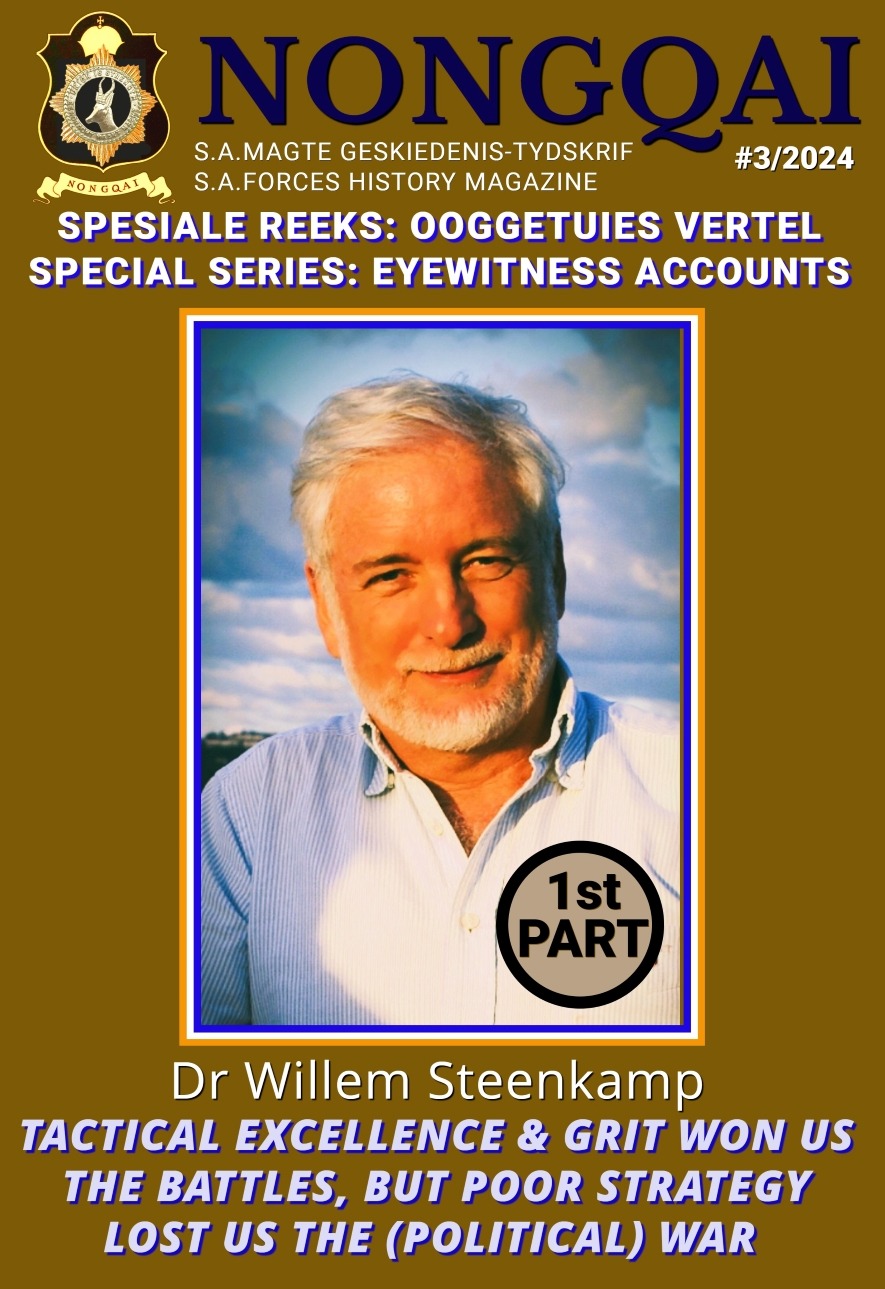

ABSTRACT: Dr Willem Steenkamp, son of former SAP-SB CO Maj-Gen Frans Steenkamp, and himself a former NIS officer who did his doctoral thesis on the intelligence function, as well as being a novelist, ambassador, attorney, entrepreneur and polyglot with wide experience of living abroad, and currently the co-editor and business manager of Nongqai magazine, shares his experiences and insights into South Africa’s transition. He gives his personal view on why and how the political war was lost, despite the “armed struggle” battles having been won, explaining that it had always been a political rather than a military conflict, with the “armed struggle” having been just one part of the propaganda war, which latter the former South African government decisively lost due to poor strategic and policy choices.

FOCUS KEYWORD: Nongqai Series The Men Speak Dr Willem Steenkamp

KEYWORDS: South Africa, Apartheid, SACP/ANC, “armed struggle”, Genl Jan Smuts, Dr HF Verwoerd, Adv John Vorster, Mr PW Botha, Pres FW de Klerk, Pres Nelson Mandela, Min Pik Botha, Genl HJ (Lang Hendrik) van den Bergh, Dr Eschel Rhoodie, Dr LD (Niël) Barnard, Israel, USSR, BfSS/NIS, SAP-SB, SADF

AUTHOR: Dr Willem Steenkamp

TACTICAL EXCELLENCE & GRIT WON US THE BATTLES, BUT POOR STRATEGY LOST US THE (POLITICAL) WAR

NOTE FROM THE EDITORS: WE’VE LEARNT FROM OUR READERS’ FEEDBACK TO OUR NEW SERIES “THE MEN SPEAK”. IT IS TRUE THAT THESE CONTRIBUTIONS ARE BY THEIR VERY NATURE QUITE LONG. THEREFORE, WE ARE NOW SPLITTING THEM INTO PARTS, SO THAT YOU CAN STOP AND RESUME READING WITH EASE IF YOU DO NOT HAVE TIME TO FINISH ALL IN ONE SITTING. (THIS CONTRIBUTION WILL SOON ALSO BE MADE AVAILABLE IN AFRIKAANS)

VOORWOORD: Brig HB Heymans

Ter wille van ons Afrikaanse lesers, ‘n kort voorwoord in Afrikaans.

Dr Willem Steenkamp is die seun genl.maj. Frans Steenkamp ‘n voormalige nasionale BO van die SAP-Veiligheidstak. Dok Willem (soos ons hom hier by Nongqai noem) is self ‘n voormalige NI-beampte met ‘n doktorale proefskrif oor die intelligensiefunksie. As ‘n romanskrywer, ambassadeur, prokureur, entrepreneur en ‘n veeltalige persoon met wye ervaring, wat Suid-Afrika vanuit die buiteland kan takseer (en tans die mederedakteur en sakebestuurder van die tydskrif Nongqai is) is ons bevoorreg om sy besondere ervarings en insigte oor Suid-Afrika se oorgang kennis te neem.

Dit louter plesier om die eerstehandse verloop van ons geskiedenis – as het ware ‘n ooggetuieverslag van vele gebeure – vanuit ‘n NI-lid cum ambassadeur cum entrepreneur se perspektief, waar te kan neem. So veel jare het verloop en ons het almal tyd gehad om te besin en om die verlede te ontleed.

Ek skat NI het maar ‘n minimale fraksie gevorm van die totale getalsterkte van die Suid-Afrikaanse veiligheidsmagte en inligtingsgemeenskap. So ook ons ambassadeurskorps oorsee. Ons is dus bevoorreg om te lees wat hierdie klein Gideonsbende wat NI en Buitelandse Sake verteenwoordig, na soveel jare vanuit die binnekring waargeneem het – die hoekoms en waaroms.

Dr Steenkamp se vertelling is heel te maal op ‘n ander vlak as die van dr Niel Barnard en ons ander kollegas soos menere Johan Mostert en wyle Maritz Spaarwater. Elke amptenaar het sy eie pligstaat gehad en het jaloers op sy eie werkterrein (“turf”) gewerk en het soms – om sy bronne te beskerm – in isolasie gewerk. Dr Steenkamp, daarenteen, het op sy persoonlike “seilskip” onder verskeie professionele en departementele vaandels laat vaar, na baie hawens. Bo vanuit sy eie “kraaines” het hy ‘n breë uitsig gehad en kon hy sleutel-oomblikke vanuit sy persoonlike perspektief waarneem, om dit nou, jare later, met ons te deel.

As skerpsinnige ooggetuie gee hy sy siening oor waarom en op watter wyse die politieke oorlog verloor is, ten spyte van die “gewapende stryd” se gevegte wat die veiligheidsmagte almal gewen het. Hy verduidelik dat dit altyd ‘n politieke oorlog eerder as ‘n militêre konflik was, met die “gewapende stryd” wat slegs ‘n deel van die magstryd was. Die som totaal van alles het deel van die propaganda-oorlog gevorm. Die NP-regering het die politieke oorlog beslissend verloor weens swak strategiese en beleidskeuses. “Ons het die oorlog gewen, maar die vrede en die politiek verloor”.

Ek dink terug na wat my professor in nasionale strategiese studies vir ons gesê het: “Al is jou skermutselings hoe glansryk – dit beteken eintlik niks as dit nie tot die uiteindelike oorwinning kon bydra nie”. Dit bewys ons was goeie en uitmuntende vegters maar ons het nie almal altyd strategies gedink nie! Takties was ons goed! Strategies hopeloos!

Dr Steenkamp was in die gunstige posisie dat hy reeds as student (in onder andere Politieke Wetenskap en die Regte), met insig by sy vader kon leer. (Net soos ek met my polisieman-vader geredeneer het en by my vader my basiese lesse geleer het oor polisiewerk.)

Dok Willem kyk dus met simpatie en begrip, maar bowenal met die objektiewe, soms ongerieflike eerlikheid van die analis, na ons geskiedenis – hoe het ons gekom waar ons vandag is, van waar ons was?

Ons sien reikhalsend uit na DELE 2 & 3 (die hele reeks sal ook in Afrikaans beskikbaar gemaak word).

PART 1: SOME HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, AND THE QUESTIONS I’LL TRY TO ANSWER

- WHY I’M WRITING THIS, AND – WHY ME?

1.1. Why am I writing this, and for whom?

This contribution is part of Nongqai magazine’s new series: “The Men Speak”. These articles consist of eyewitness accounts and insights about our national security history, provided by those of us who were actually there: in the Forces, the intelligence services and/or the diplomatic corps. Our own truth, as we lived it, and how we then understood it. Plus – above all – how we now reflect upon it. Of course, doing so now with the wisdom of hindsight, maturity, and often more information than what we possessed back then, when everything was subject to a lot of “spin”.

I will not be boring you with a full chronological account of my life’s “exploits”. This is a “fireside chat”. It does not pretend to be an autobiography.

What I hope to do, rather, is to try and answer some fundamental questions about the twists and turns of our history. The “why’s and wherefores” that I believe most of us (and our friends and family) are keen to have answers to. It is around these questions and answers that my tale and the events that I’ve selected to tell you about, will be structured. I’ll be the first to admit that it is, therefore, partial and a very personal view – sharing my interpretations and conclusions, as best I’ve been able to figure these complex things out for myself. To my mind, you are absolutely entitled to differ from me, to have your own opinions – but then, so am I, not so?

I will not be writing this in a formal, academic manner. Therefore, no footnotes or stacks of references. Rather, I’ll try and keep to a less formal style, as if discussing with family and friends around a Bushveld campfire. But always sticking to what I believe to be the truth, as I know it from my own experience. Supplemented by what I’ve since reliably learnt about so much that have not been generally known back then and which often remains so to this day).

South Africa still face great challenges. It is, therefore, critically important that we learn the lessons that our history can teach us. That is why I’m sharing this – for the sake of learning for the past. From the answers (as I see them) to the questions about what brought us to where we are today.

1.2 The fundamental question I will try to answer:

Most of us who, during those years of tumult, were personally involved with intelligence and the security forces, have been confronted with one fundamental set of questions. Coming most often from family and friends. Questions that most of us have, ourselves, pondered – over and over – these past three decades.

Fundamentally, it boils down to this: “How come? How could the once mighty South Africa go from where it was in the mid-nineties, with all the hope then, to where it is now?”

Typically, we are told (often a bit accusingly) something along these lines: Back then, the JSE was among the ten largest bourses on earth. Eskom was rated one of the top utilities in the world, delivering the cheapest electricity on the planet. Baragwanath was a world-leading hospital, to which foreign medical doctors streamed for post-grad study. Homes were secure, even unfenced, with criminals fearing and respecting the efficient police and courts.

A South African matric was still internationally recognised and our universities were highly regarded. South Africans could travel to the West without visas. Flying abroad on our own national airline…

By the late eighties, the security forces had effectively neutralised the ANC’s MK, pushing their nearest bases to Uganda. The SADF was the most combat-efficient military on the content, with a functioning Navy, Air Force and Armoured Corps. South Africa was a nuclear power, with RSA3 ballistic missiles that could target the Northern Hemisphere.

At that stage, you guys had even turned the USSR around! Despite UN sanctions and the arms embargo. So that, by the end of the eighties, your aeronautical engineers and theirs were working side-by-side in Moscow (in Brezhnev’s old dacha, of all places) successfully re-designing the MIG-29 jet engine. You fitted this into SAAF Mirages as a powerful upgrade, which flew great! Then ANC president Oliver Tambo could no longer get appointments with the USSR’s Michail Gorbachev, but the Soviet boss shifted a politburo meeting to be able to see the DG of the NIS, there inside the Kremlin!

You guys prevented that a Marxist People’s Republic be established in South Africa. National Intelligence and the Security Forces were pivotal in convincing both sides to the conflict that they had to stop shooting and rather settle through negotiation. The security forces provided the stable environment that enabled those settlement talks and then the transition to unfold. The world was thrilled and supportive, backing President Mandela’s vision of a “rainbow nation”. Our economy bloomed, we were the toast of town, after the tough years of international isolation…

But now? The Rand is worth just 4% of what it was against the dollar in its heyday. We have a dysfunctional state with a disastrous incapacity to deliver essential services and a shocking inability to maintain the once excellent infrastructure. Ironically, Blacks suffer more than ever – from poor housing, risible education, rampant crime, inadequate health care, craven corruption, and shocking joblessness. The list of ills goes on and on, too long to enumerate.

Before 1994 your guys were in charge – you, the white Afrikaners. Your people had taken exclusive control of the country’s destiny in 1948. You set yourselves apart, and your leaders determined all strategy and policy! The responsibility for the run-up to where we are today, was therefore yours!

Now it is so that you (Oupa, Uncle, neighbour…) were there, in the midst of it all – so, please explain: How come? How did we get here?

Author’s Note: My granddaughter and sons-in-law are actually English-speakers (non-South African); you will therefore understand why I am writing this in English. This will also explain to you why I will be including here, in this first part, a quick overflight of South African history. It provides some context for understanding the larger trends that helped shape the era which I had been part of. I believe that this background is not only useful for “uitlanders”, but most likely is also a useful “memory-jogger” that will help my fellow South Africans reading this, to recall those long-ago times.

1.3. Why me? What qualifies me to try and answer these tough questions?

In my 70 years to date I have been blessed with the opportunity to have lived what has amounted to a number of quite distinct “lives”. These sets of experiences were identifiably distinct from one another in terms of the different entities and capacities I worked in, each with its own focus. Nevertheless, as regards the over-all picture of our history, they were inter-related: security, intelligence, diplomacy, academia, practising law, engaging in business, plus experiencing other cultures and their solutions to similar challenges. Last, but not least, I need to include here the learning that flows from lately having been closely involved with Nongqai magazine and the constant stream of historical data that flows across one’s desk in that capacity.

What each “life” did was to provide me, as keen observer, with an additional vantage point, a further illuminating angle. It gave me opportunities for learning first-hand new facts (and ones probably not commonly known to the general public, at that), plus experiencing the customs and outlooks particular to those different sectors and institutions. All of it, very relevant to those core questions. Because it allowed me to comprehend the interplay between all those role-players. Through this multi-faceted learning opportunity, I could develop a more broadly-based and balanced understanding of South Africa’s complex history.

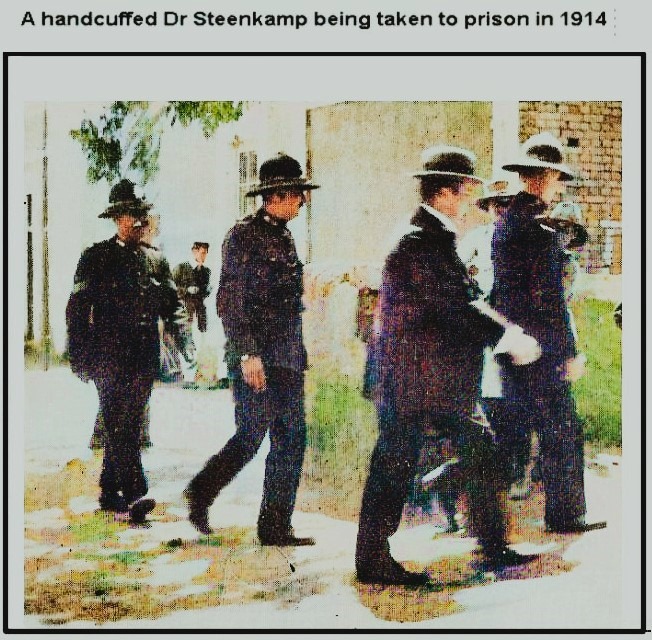

1.4. Learning from my SAP-SB father:

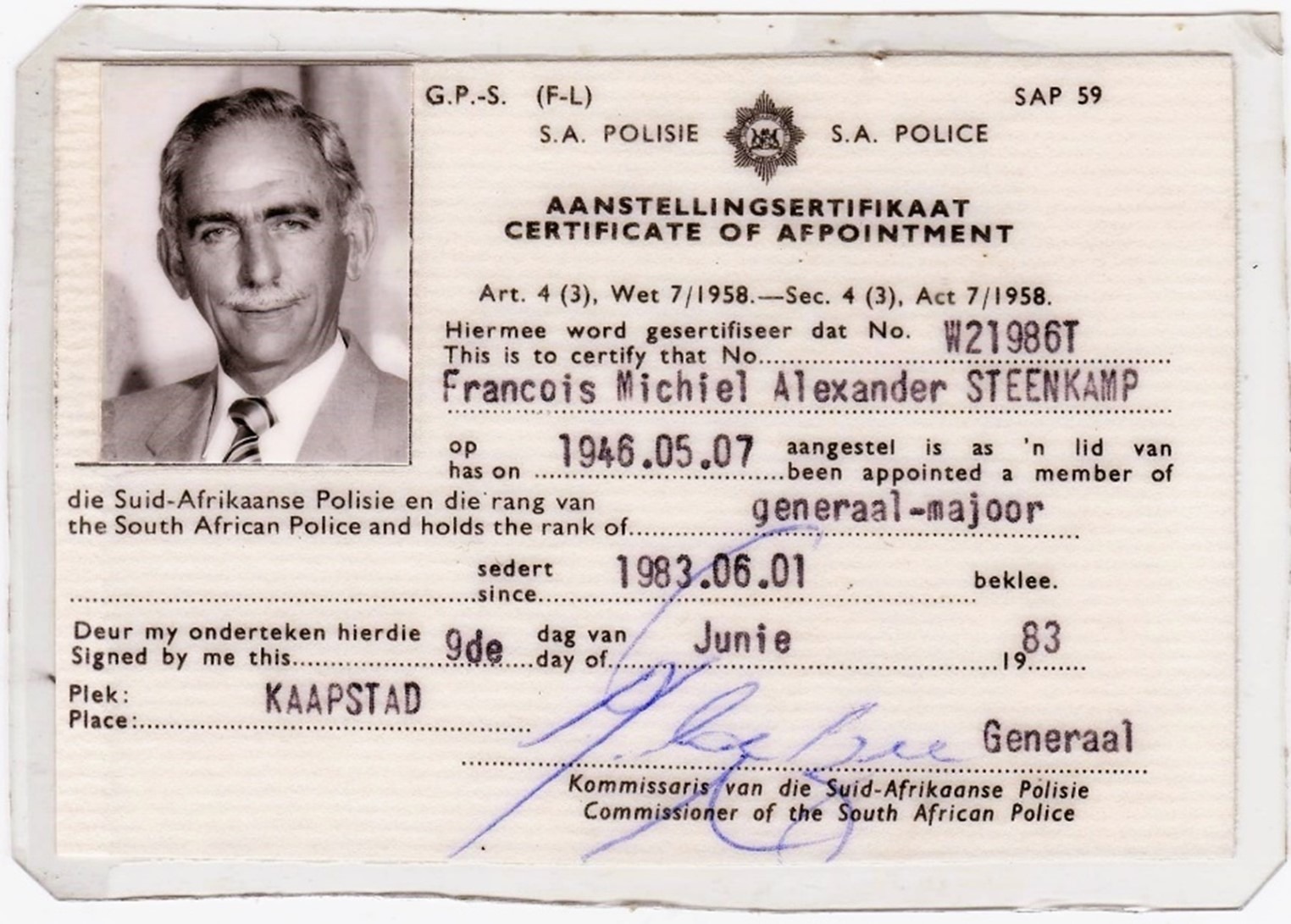

First off, my understanding of our security situation (and particularly, of the SAP-SB’s role) owed much to my early exposure as the son of an SB officer. My dad, major-general Frans Steenkamp, eventually became the commanding general of the SAP-SB nationally (before he took early retirement because of policy differences with the PW Botha “total onslaught” approach).

We never discussed operational details, but the way that the country was going was of course a serious and frequent topic of conversation between us. In my early years, sitting at his feet, listening, while he and the “groot ooms” were discussing national affairs. I particularly recall the many fascinating hours on the quay-side in Durban harbour, listening to him and his great friend Colonel Hennie Prins of the security branch of the Railways & Harbours Police discussing matters (they were both keen anglers).

Later on, when I had joined the intelligence service and also held “top secret” security clearance, discussing in confidence, more in depth, as father and son would.

My father, Frans Steenkamp's certificate of appointment as major-general.

1.5. As a child, I was interested in national and world affairs from very young:

From a very early age I had a keen interest in politics, being glued to the radio at news time. Well before school age, I could name all the African heads of state, their countries and their capitals, to the amusement (and astonishment) of family and friends. This inquisitiveness stood me in good stead in my matric year, when I led our school team (Dirkie Uys High School, Durban) into the finals of the SABC’s general knowledge quiz for high schools. I also in that year (1971) won the national inter-school debating contest for Afrikaans-medium high schools.

At university I majored in both Law and Political Science, culminating eventually in being admitted as attorney, as well as obtaining my doctorate in Political Science with a thesis on the role of the intelligence function within the political system. My undergraduate studies were at Bloemfontein, with one of my bursaries having been from the then Public Service Commission, which I then had to “work back” by labouring in some or other government department for an equal number of years. I also had to meet my compulsory national service obligations.

The solution was to opt for a department where I could do both at the same time. Thus, in 1975 I joined the then Bureau for State Security (BfSS), which later became the National Intelligence Service (NIS).

In the erstwhile Bureau I soon found myself in positions of responsibility, so that I quickly had a Top Secret security clearance. As, my father and I never discussed operational details, but we had many, many discussions about over-arching strategy and policy. The same applied to my wife, who was also an SAP-SB officer – then one of the “handlers” for Operation Daisy. Because of our training and conditioning, we never-ever discussed operational detail about our respective responsibilities, but between them I did indeed get as good an insight into the SB as any “outsider” probably could hope to get.

1.6. My career in the BfSS/NIS:

My nearly decade-long stint inside the intelligence apparatus (which I will come back to in more detail later, in Part Two) provided me with insights into the burning national security issues of the day, from the mid-seventies on. First as analyst, but towards the end also on the clandestine operational side.

Through a convergence of happenstances, I was privileged to have found myself (despite my tender age) at excellent vantage points from which to observe key developments. One such was as head of the then seriously topical SWA/Namibia section, at the end of the Vorster era / beginning of the PW Botha “securocrat” (i.e., military) reign.

Atop the Grootfontein meteorite, SWA/Namibia 1979 (note the long hair and “blush of youth”, which often confounded my high-ranking uniformed counterparts)

Another was when I was subsequently promoted to the position of deputy head of the central editorial division of the NIS. This position also entailed serving at inter-departmental level as the secretary of the Coordinating Intelligence Committee, or KIK (which dealt with top national priorities, such as when to release Mr Nelson Mandela from prison – as said, more about that later).

Photo that I took at “Checkpoint Charlie”, between East & West Berlin (1980)

After having met my bursary and national service obligations, I left the NIS and served articles at a varsity friend’s legal practice in Frankfort in the Free State. I duly passed the Bar exam, which allowed my enrolment as practising attorney. However, I wasn’t then yet ready to dedicate the rest of my life to being a lawyer. (Nevertheless, I had wanted to have this qualification in my back pocket, given that one could at that stage already see that the civil service in future may perhaps not be a long-term career prospect for a white South African male, particularly of my background).

1.7. The Foreign Service and ambassadorship:

Because my wife and I had both wanted to see a bit more of the wide world out there, I joined the Department of Foreign Affairs. Again, I could shine in the training. By tradition, through coming first in my cadet group, I could choose which of the available postings I preferred. I chose Paris, where I served as first secretary.

After that tour of duty, I was appointed head of the diplomatic academy in Pretoria in 1990. I was charged with integrating the recruits from the former liberation movements and with thoroughly revamping the entire training system to make it apt for the needs of the New South Africa.

After that, I had the great honour and privilege to be nominated as the New South Africa’s first ambassador to formerly hostile Black Africa, at the tender age of 38. My residence was in Libreville, Gabon, with my bailiwick further including Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Sao Tome and Principe, and the Central African Republic.

Presenting my letters of credence as ambassador, Libreville, Gabon (1993)

My diplomatic career stretched from 1985 to the 1997. It amplified my understanding of South Africa’s challenges and opportunities, particularly as viewed from an international perspective. The experience that had struck me most, was how completely I (a white Afrikaner) was accepted as being fully and equally African by my fellow African ambassadorial colleagues.

1.8. Franschhoek law practice, with community & business exposure:

My life as practising lawyer also spanned roughly a decade. It followed upon my return to South Africa in 1997, after my term as ambassador had ended. I established a thriving law practice in Franschhoek in the Cape Winelands, a region of high-value clients. Because of their needs for legal services in the fields of administrative and commercial law, the firm of attorneys that I set up was largely focused on those areas where business and government interfaced. This involved things like property development, environmental and heritage conservation issues, housing and Labour law. My legal practice quickly expanded to serve and represent large institutions such as the Stellenbosch Municipality and the national forestry company SAFCOL, as well as business clients with specialist needs from across the Western Cape Province.

In Franschhoek I found myself in the somewhat unique position that I was, at one and the same time, elected by fellow Franschhoekers as chair of the local branch of the Afrikaans cultural organization the Rapportryers, as well as of the Community Policing Forum and the Neighbourhood Watch, plus the chamber of business. I was also elected as member of the regional executive of the ANC of president Nelson Mandela (as a lifelong confirmed nationalist patriot, and with the demise of the erstwhile National Party, I saw Mandela’s party as the only remaining viable nationalists – I certainly wasn’t ready to become an Afrikaans “agter-ryer” for the Progs; however, the advent of the Zuma presidency immediately had me terminate my ANC membership!).

The trust invested in me by all sectors of the community, allowed me to pilot the ground-breaking Franschhoek Social Accord, which resolved long-standing conflicts in the Valley that had resulted from the Apartheid legacy. This new harmony of common developmental objectives across the community, plus the financial support I could mobilise from the French government, the Development Bank, and the private sector, helped wrench Franschhoek from its stagnating era of community conflict and launched it on the road to the prosperity it now enjoys.

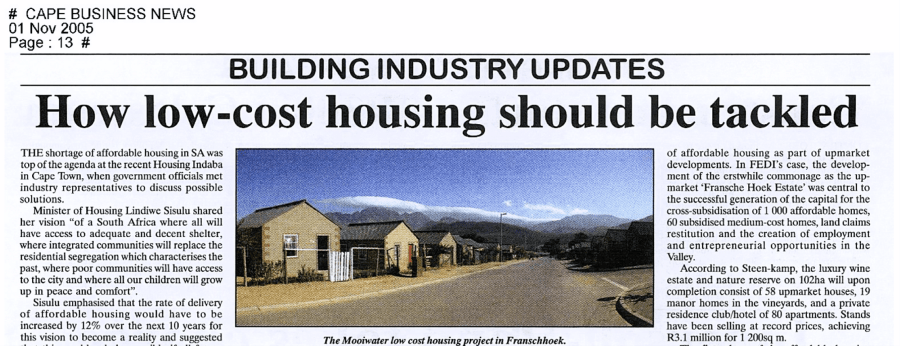

The “Franschhoek Empowerment and Development Initiative” (FEDI was the cornerstone of the public / private / community partnership. It made possible that more than a thousand quality new starter homes could be designed and built to way above the “HOP-huisie” (RDP) standards. This was done by the private sector (not the municipality) for the previously homeless, who received full title to their new properties entirely free.

The new township of Mooiwater came with wide tarred roads and all the services such as electricity done properly, buried underground. All this was achieved through cross-subsidisation by the private sector, without burdening the local taxpayers. The project was lauded by the Western Cape as well as the national government, and even by the United Nations – it was, for example, selected to represent South Africa in France at the largest annual international property development expo, MIPIM.

Its success showed me what can be achieved through community cooperation, despite our polarized historical legacy.

Part of the positive media coverage which the FEDI project generated

In Franschhoek I also gained valuable entrepreneurial experience and insight into the relationship between big business and government. It stemmed from being the CEO of a quite substantial upscale property development company, FRANDEVCO Pty. Ltd.

Among my shareholders and partners on the board were the V&A Waterfront company, plus leading South Africans such as fellow former ambassador Dr Franklin Sonn (then national president of the Afrikaanse Handelsinstituut), my neighbour John Samuel (who then headed the Nelson Mandela Foundation) and top South African and international entrepreneurs with ties to Franschhoek, such as Gordon Jones and Peter Middleton.

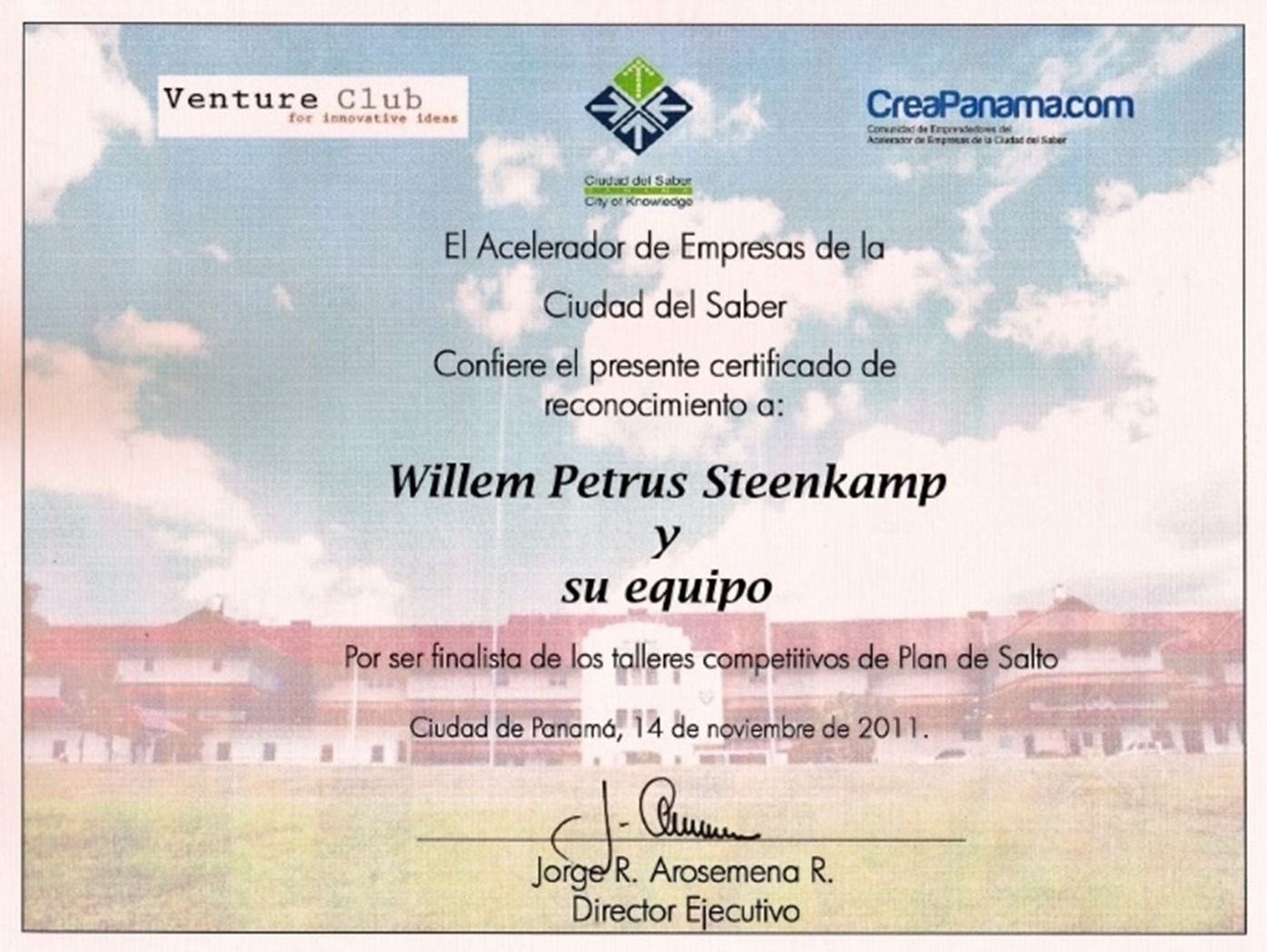

In later life, while residing in Central America, my business exposure expanded further; a project that I had initiated won Panama’s annual contest for the best new business idea, winning me a study trip to California’s Silicon Valley, focused on IT applications in business. I am also an American-certified professional business coach.

Panama’s “best new business idea” contest, which won me a study trip to Silicon Valley…

My experiences of the world of entrepreneurship have allowed me to view important national issues also from the private sector perspective, supplementing the public sector experience I had gained while working in intelligence and diplomacy.

1.9 Academic researcher, novelist and Nongqai co-editor:

My knowledge and understanding of national security, intelligence and diplomacy doesn’t only stem from having actually worked in those fields. I also benefited from my schooling as academic researcher. My doctorate in Political Science (attained through UNISA) had as theme, the role of the intelligence function within the political system. This was an analysis of how intelligence systems could in theory best function, in any political system anywhere. The aim with the study was to better understand the role of intelligence in supporting the making of decisions.

One of the external examiners of my doctoral thesis was the world-renowned Cambridge University expert on intelligence and also official historian of the British MI.5, professor Christopher Andrew.

Apart from my professional intelligence training with the BfSS/NIS and the German Bundesnachrichtendienst, I therefore also had a very focused and theoretically sound academic grounding in the subject matter. This was further enhanced by my academic training as lawyer, with its strong focus on analytical skills and on the moral / philosophical foundations of jurisprudence and governance.

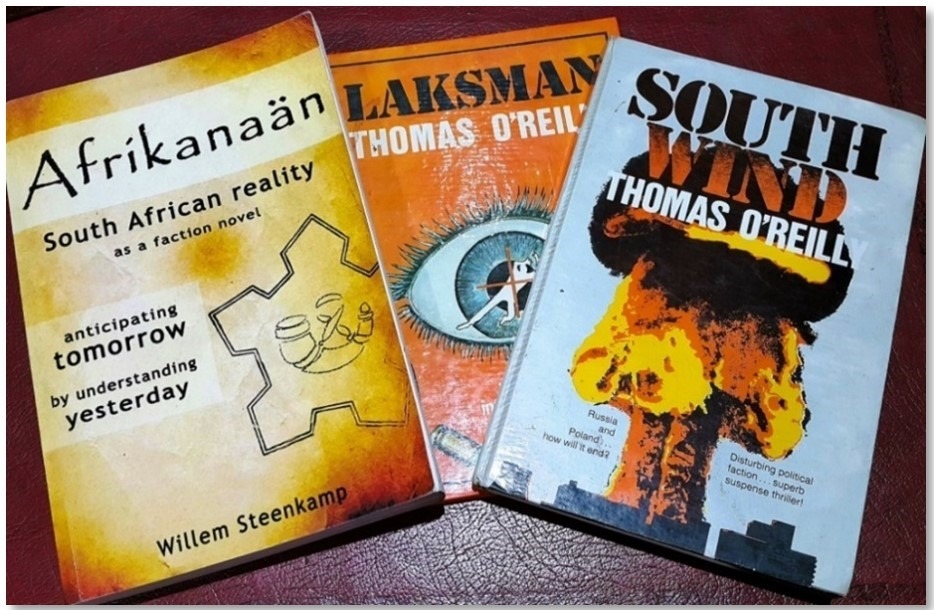

My trajectory as a published author of so-called “faction” (fact-based fiction) also provided a surprisingly strong grounding in research and analysis – it is amazing how much research and thinking goes into any one such manuscript!

In the same vein, my association with Nongqai magazine has been hugely valuable in broadening my factual knowledge as well as my understanding of the last decades of white rule in South Africa.

Firstly, through the constant stream of information about that era (much of which had earlier been classified or suppressed, such as the verbatim transcripts of the meetings between the teams of premier Vorster and Dr Henry Kissinger in Germany in the mid-seventies, or of the PW Botha cabinet “bosberaad” just prior to his “Rubicon” speech).

Secondly, through talking with eyewitnesses to important yet unreported events. An example of the latter was my on-the-record discussion with the police bodyguard who sat in at a private lunch between Judge Erasmus and Minister Pik Botha. He heard how Pik Botha pointedly coached the judge Erasmus (who then headed the supposedly independent Erasmus Commission into the so-called information scandal) on how to politically sink Dr Connie Mulder and then-president John Vorster – later, more about this.

Thirdly, through the vastly enriching intellectual interaction with my fellow editors, in particular Brigadier Hennie Heymans. This helped sharpen and deepen my understanding of the “how” and “why” of key events.

1.10. Experience of having lived in other countries / cultures:

The last important contributor to my broader understanding of South Africa’s complex situation and of the impact of its historical context of European colonialism, has been my decades of having lived abroad. My latter years spent in Latin America and actually imbibing their culture (through marriage) has been especially helpful. This has provided me with a basis for comparing our Anglo experience with their Spanish / Catholic one, giving me insights into what perhaps could (should?) have been, under a different system…

What has been striking has been the similarities, yet also the fundamental differences between these colonial/cultural legacies. The Americas, like South Africa, had been colonised by force. In the Americas, some highly advanced civilizations (light years ahead of those in sub-Saharan Africa), had been violently conquered and subjugated. Some by Spain, and those of North America by England.

One finds a huge difference between (Anglo) North America on the one hand, and (Latin) South & Central America on the other. Differences in wealth, yes (where the Anglo countries are clearly better off) but also with regard to race relations (where the Latin countries have fared much better). South Africa, as an ex Anglo colony, corresponds to the formerly overtly and institutionally racist North America. Leaving us with the same heritage as the USA’s still hugely reacilally polarized society.

Why this difference between the Latin and Anglo colonial legacies? Why is it that, to this day and despite the fact that in a country like Guatemala (my wife’s home, where I now live) the “whites” constitute less than 2% of the overall population, “white” Guatemalans are time and again entrusted with governing? This, by an overwhelmingly darker-hued electorate – in free, democratic elections.

My objective is not to judge here whether this is either good or bad, nor to suggest that Guatemalans, or Panamanians, or practically any other Central American nation vote for their leaders because of race (they do so on the basis of perceived merit, competence and experience, irrespective of race – as it should be).

What I will try and share when later I deal with this phenomenon, comparing South Africa to Latin America; is WHY this is happening. Why is this still the empirical reality here, after 200 years of independence? (Reflecting nations sufficiently at peace with their diverse heritage, allowing diverse voting blocks to be realistic about the fact that their own interests are best served by merit-based selection of ministers). A very different situation indeed, to the Anglo colonial legacy of deep, persistent racial polarization!

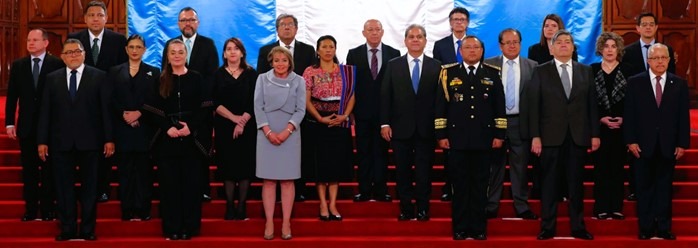

In the recent elections here in my wife’s country, Guatemala, the most progressive / liberal party in seventy years won – thanks in very large measure to the vocal and activist support of the indigenous Maya majority. And yet, even though the new president went out of his way to appoint an equal number of male and female ministers, he was the first to apologize for the fact that only one minister of Maya origin was appointed. He openly ascribed this as being due to a lack of suitably qualified and experienced candidates from that group, pledging to work to improve that reality.

His apology and explanation of his reasons were accepted. And this example is not unique in the region, but rather the norm.

2024 Guatemala cabinet (ministers and deputies) with only the lady at centre in traditional dress a Maya.

What is at the root of this? I will discuss the reasons behind it in detail later. However, just to set you thinking – in my experience, it is due to the historically distinct roles and influence of the main churches of the respective sets of colonizers. Without promoting any one over any other, the evidence shows that the Catholic approach in the Americas was to emphasize that God’s flock is one and indivisible, despite stemming from different peoples (this is due to the reported appearance five centuries ago in Mexico of Mary, mother of Jesus – known as the Virgin of Guadalupe apparition – where she is said to have strongly conveyed this message).

It needs little argument that the 20th century NG Kerk and its eventual full-blown justification of Apartheid, had the complete opposite emphasis… (again, more about this in Part Three, with my conclusions).

1.11. NB – why I briefly listed here my life’s trajectory:

I want to stress that I haven’t listed my diverse range of qualifications and experiences above, to try and impress! I did it, hopefully to help convince you as reader that I do have some reason and justification for my very broad perspective on South Africa’s history. As you can see, it’s a multi-faceted viewpoint that goes well beyond having participated in just one national security-related profession, or in a particular branch of the Forces, or one academic discipline.

- THE KEY QUESTIONS I’M TRYING TO ANSWER (determining the structure of my story)

2.1. My basic approach:

I want to avoid that this contribution of mine becomes just a chronological re-telling of random experiences, with then some conclusions tagged on almost as afterthought at the end. That kind of approach will firstly make it far too long, and secondly far too haphazard and unfocused / unstructured, to be of any real value.

Therefore, I’m going to identify here in Part One (as briefly as I reasonably can) the key questions I’m going to try and answer about how we as nation got from where we were, to where we are now. I will then also, here at the outset, briefly outline for you the essence of the answers that I’ve come to. Why I’m going to do things this way, is so that you can test my conclusions as my story unfolds. Kind of like having a golden thread to follow through history’s maze. In the end (Part Three), I will return to those questions and answers in more detail, in an assessment and explanation of the reasoning behind the conclusions I’ve myself come to.

I also believe that it is important to not get caught up in too much cluttering detail. It is essential (as the saying goes), to be able to “see the forest for the trees” – in other words, to be able to look through the branches, leaves and trunks and distinguish the big picture beyond.

I will, therefore, be selective in Parts Two and Three and only talk about those experiences of mine that are directly pertinent to the answers I will share with you. Answers about why I believe things happened the way they did (or could perhaps have turned out differently, if other strategies had been adopted). My focus will therefore be on what I see as having been the absolute key fundamentals that caused us to end up where we are. Because, when we are too invested in the (un)savoury day-to day detail, we often lose sight of these core factors.

To illustrate this last point: one such basic reality (if one sets aside all the detail about policies and legacies) is simply this: South Africa had, at the end of the last century, in the great panorama of history simply found itself as the last remaining colonial state under fair-skinned rule. This, in a world that had come to abhor both racism and imperialism after the Second World War.

As the USA secretary of state Brzezinski had warned, we were simply trapped on the rail track of history, with the locomotive of time rushing unstoppably towards us. Inevitably, given the reality of the overwhelming power of that world-wide historical trend, the “old” South Africa (or any other ex-colony that would have found itself as the “last one standing”) simply would not and could not have escaped undergoing fundamental political change of some or other kind.

One now realises that the only truly relevant questions were, therefore: what would be the nature of the New South Africa; and, would that fundamental change come about through a war of national liberation (as happened elsewhere in the world) or through a negotiated internal settlement?

Since you have just read about my own background, you will understand that I will be approaching these questions from who and what I am – an Afrikaner. Not a “super Afrikaner”, for that I never was (in fact, I had many a run-in with that kind, right from the days of my youth).

I have always regarded myself as first and foremost a proud South African, a nationalist patriot, and then as a proud speaker of the Afrikaans tongue. Regarding my mother tongue, I always saw speaking Afrikaans as impossible to associate with colour – after all, the roots of our language undeniably goes back originally to what under the English became known as the “Coloureds”, more specifically to the Cape Malay community. My nationality was (and still is, to this day) South African, while my cultural heritage is Afrikaans. I do not speak “white”; I do not see myself culturally having more in common with English-speaking “whites” than I have with fellow Afrikaans-speakers who happen (to a varying degree) to be of darker hue, but who love the same sport as I do, belong to the same faith, and love the same country. And this does not mean that I do not value and appreciate the English language, or my fellow English-speaking countrymen – or be they of whichever of our other language groups.

Fact is, we Afrikaners ruled the unified South Africa from 1910, and exclusively so from 1948. When I will talk in this contribution about policies adopted and strategic decisions made, those were “our” decisions and “our” policies, as made by our leaders and supported by a majority of us, the white Afrikaner voters – myself oncluded. Of this reality I need to take ownership in this contribution, otherwise I’d be denying self-evident facts.

I’m therefore not going claim here that, back then, I already somehow had clairvoyantly “told you so” in advance. I myself had headed National Party formations, for example as member of the Natal provincial executive of the Jeugbond (youth wing) in my school days, and as branch chair in places like Frankfort. I had chaired our local chapter of the Junior Rapportryers in Central Pretoria during my NIS days and chaired the senior Rapportryers in Franschhoek. I cannot and will not hide from who and what I had then proudly identified with.

Not that this is going to be a breast-beating mea culpa, covering myself in cloth and ash. I am very proud of my personal trajectory, of my Afrikaner people, and – for that matter – of our erstwhile security forces (despite individual cases of wrong-doing, which I admit occurred and which I abhorred, then and now).

Let’s face it: if the other side had not abandoned their dream of a Marxist People’s Republic and were still today trying to impose it through the barrel of a gun, then I know that I would still now be fighting tooth and nail to oppose it!

Of course, we are all human and mistakes were made – on all sides. Being proud of us and our past does not mean that one cannot or should not now, with the benefit of hindsight, admit to mistakes. Because if we don’t admit to them, then there will be no learning from the past. Yes, there were mistakes on our part, some very grave – immoral mistakes, even, although most now simply appear stupid and senseless (with a great many also having been driven by unchecked personal ambition of unscrupulous politicians from our ranks) Which, again, is not unique to Afrikaans politicians, but a familiar gripe the world over and through-out time.

My message about how we got where we now are, will be focused on decisions that had often been taken tactically, for short-term political gain (based in the gut instead of the brain), which have brought us lasting strategic harm.

It is easy to fall into the trap of only lamenting a litany or errors in a story such as this. As if all was darkness and sin. Without recognising the much that was good that our forebears had done. Of which we still enjoy the fruit. Absolutely fundamental choices they had made, and which had set us on a different course to other descendants of European colonial settlers elsewhere. Fundamental choices that at the time surely appeared extremely “liberal” and “progressive” – but which has stood us in such good stead (compared to the negative consequences of the “conservative” choices we as a people had made).

Let me explain: compare our present situation to that which befell the French “pieds noir” in Algeria, or the British settlers in Kenya and Rhodesia, or the Belgians and the Portuguese in Africa (for that matter, descendants of generations of white settlers in Africa and Asia, during the colonial era). When “Uhuru” came they were all viewed as settlers, and they all lost everything, obliged to flee.

We, however, are viewed as being as much African as any other group. Why? Because, unlike other white colonial arrivals (who all had clung to their “home” country across the waters, and to that language) our forebears from very early on identified with our continent, and even adopted the locally-rooted Afrikaans language of the Cape Malays and so-called “Coloureds”, forsaking Dutch.

And, we were the first Africans to take up arms against imperialism. By any measurement, the Afrikaners are the Africans who suffered the highest losses in wars of independence fought against colonial oppressors – more than 40,000, including up to 50% of the children of burghers of the Free State and ZAR, during the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Those were then revolutionary choices, which now ensure that we are still very much part of South Africa, the beautiful – not unceremoniously expelled back to Europe…

These were the most fundamentally important choices ever made relevant to our well-being as a people; and they (and their consequences) are hugely positive. So, when we will list here some of the errors also made (so that we can learn from them) let we never forget that our forebears also made exceedingly good, often unique, choices as well – especially when they were guided by their highest moral principles and dared to be “progressive”, to proudly be themselves…

As with most nations, there were also prophets not recognised in their own land, by their own people – such as a Jan Smuts, a John Vorster, Beyers Naudé or Breyten Breytenbach. Our churches over the past century had deviated from the narrow moral path when it came to preaching politics and justifying the patently unethical (although there were enough senior Afrikaner theologians that at the time had warned against Apartheid, at great cost to themselves).

Then there was big business, which had made hay while the Apartheid sun shone, without using their influence appropriately.

Our Afrikaans schools and universities had promoted dogmatic group-think, rather than independent investigation and critical thinking. Our media toed the party line.

The “enforcer” behind all this groupthink was the Broederbond (of which neither I nor my father ever were members, nor wanted to be). Not all-powerful, as some may believe, and increasingly lacking in clear direction and unity at the end of the seventies and through the eighties. But which nevertheless – through its implantation in church, media, education and the public service – contributed hugely to the suppression of free thinking among white Afrikaners.

Especially what should have been free expression of critical thought in our media, from the pulpits and in the classrooms and lecture halls, which would have fostered healthy debate. This cultivation of groupthink was the consequence of the Broederbond’s focus on “maintaining Afrikaner unity” at all cost, but which had in reality morphed into enforcing a blind, unquestioning herd effect through social sanctions “excommunicating” those who dared to step out of line.

As membership of the Broederbond increasingly became seen by many as a means of self-promotion (particularly within the public service and the Forces), it gave rise to “baantjies vir Boeties” – the promotion of fellow members and “gat-kruipers” (brown nosers) over those who dared to think for themselves.

And after 1994, under an ANC government? What I have found with my ANC acquaintances post-1994, is that – similar to the aftermath of most wars – the actual opposing combatants get along fine afterwards. There is respect, when you show your pride and don’t try to hide or fudge. For the bleeding-heart liberal there is very little respect or sympathy.

I always made very clear that, yes, I was a Nationalist. Yes, I did serve in the NIS. And, yes, we were excellent at our job, which was to prevent you guys from winning and imposing the disaster of a Marxist People’s Republic. Yes, we gave you a hard time (a reminder which often then resulted in comparing notes). But please don’t believe your own propaganda – you know that we were not waging a “dirty war” like the one the Americans promoted in Latin America (otherwise, if we really had done all that, you wouldn’t be here to enjoy the fruits of your negotiated liberation!). And we’ve always kept our word not to divulge who our legion of informers were…

2.2. The structure of my story:

Recounting a lifetime of experiences in purely chronological format can be very frustrating (and also less than illuminating) for readers. Because life typically takes so many irrelevant twists and turns. So much of what happens to any given individual is simply no more than mundane or irrelevant to understanding the big picture.

What I’m going to do now, here in Part One, is to set out briefly how I’ve come to view the “why’s and wherefores” of the history of our people. In Part Two I will then launch into my own years of first-hand exposure to security intelligence (learning first from my father, plus while serving in the NIS). Part Three will be dedicated to my years as diplomat, ultimately as ambassador, and the insights I gained from that experience.

The experiences that I will share are chosen because they illuminate the events and causal factors that, in my humble opinion, most pertinently contributed to shaping and directing where we are today. In the life of any nation there are many forks in the road. Many decisions on policy, tactics and strategy that needed to be taken. Oftentimes, choices that later turn out to have been less than optimal – made for short-term tactical gain, which then resulted in long-term strategic harm. Some decisions that were “good”, some “bad”, and most probably middling.

But how do we judge whether those decisions were in fact good or bad? And when do you judge that? (Because what may have looked good at a certain stage, may later – as the consequences emerge – turn out to have been very bad indeed…).

The only “scoreboard” we can use to assess the real effect over time of any given past decision, is to look at its results, here-and-now. In other words, we have to judge whether that decision had – objectively assessed – bettered the security and well-being of our interest group (the Afrikaner). Or, whether we are now actually worse off because of that decision, in terms of all the factors affecting our security and well-being – factors such as our current standing (how we are perceived), plus our relevance and leverage in influencing present-day decision-making affecting us and the country, and the prospects for our children.

Of course, none of us can turn back the clock. There is no possibility of a “re-do” of history. What is done, is done. Therefore, the only true value in going through such an exercise of navel-gazing here, is if we are going to learn something from it. So that we don’t repeat, in future, the mistakes of our past. And understand why good decisions resulted in positive results, to emulate in future.

To this end, one’s assessment needs to be clinically objective and honest. Sometimes brutally so. An unsentimental facing of the facts. Without getting emotional about it, and without morbidly dwelling on allocating blame. (As our Nongqai motto says: “To preserve our national security history without malice”). Therefore, not to engage in polemical exchanges about this one or that having most contributed to some or other perceived calamity. And not to waste time with excuses, self-pity, or self-justifications. Nor with saying: “Yes, but the other side did worse”. (Which may well be true, but which is irrelevant, if our aim is to learn from our mistakes).

The purpose of beginning in part one with an overview of our history (a sketch of how I now see “The Story of Us” from a national security decision-making perspective) is firstly to provide historical context, of course. Secondly, it will also then hopefully allow you as reader to test these personal insights of mine as we continue on to the experiences and facts that I will subsequently share with you in Part Two and Three. So that you can judge whether my experiences and related facts, justify my conclusions, also when weighed against your own experiences and knowledge.

In other words, so that you may, right from the outset, understand where I will be going with this and start testing in your mind the validity of the answers that I’ve myself arrived at to that key question of “How come”? How did we arrive here – going from where we were, to where we are today?

- “THE STORY OF US” – MY TAKE ON WHAT SHAPED OUR PAST AND PRESENT

3.1. Who are “Us”?

When I talk about “us” I am, as a personal conviction and born-with condition, principally talking about those South Africans and Namibians who speak Afrikaans as mother tongue. All of them, irrespective of their hue. I’m not focused on this group in order to glorify us in relation to other equally worthy groups of Southern Africans, or to play groups off against one another, or to suggest that we should have any special privilege. It’s simply that this is, in fact, my ethnic group (however, please keep in mind that I’ve always been proud to say that I am first and foremost a South African).

Secondly, as I’ve explained in the previous segment: when one wants to judge whether a particular past decision was “good” or “bad”, you have to do so in relation to the consequences it entailed for a particular group. In a pluralist society such as ours, it is not possible to adopt a generalist or normative yardstick with which to measure the impact of decisions. Because, most often distinct groups were touched very differently (often intentionally so!) by the self-same decision. One is therefore obliged to define the particular group whose interests you will use as test case, to be able to judge the outcome engineered by a particular policy or strategy choice.

When I say that, to me personally, “us” should mean all who speak Afrikaans, I’m not blind to the reality that the race policies of particularly the period 1948 – 1990 meant that practically all political decisions of consequence were in fact taken by “white” Afrikaans-speakers, with so-called “coloured” Afrikaans-speakers more often than not the fellow victims of those decisions, together with the other non-white groups of our country. Therefore, if blame is to be apportioned for decisions that we now adjudge to have been wrong or bad, that blame attaches exclusively to us who then had the monopoly on the vote by reason of the lightish colour of our skins.

Before I start summarising the history of “us” here in Southern Africa, I believe it is also necessary to point out a few basic truths about human history in the world at large, and in our continent in general.

3.2 The History of the World is one of endless Migration and Conquest:

All through time and everywhere humans have settled, the history of our species is marked by constant migration of people and tribes. New arrivals who displaced existing inhabitants by force of arms, through conquest. The point is not whether this is morally right or wrong; fact is, it has always occurred. Which means that practically all peoples who now have a gripe against any other group for having been recently vanquished by them, themselves earlier in time had more than likely moved in and conquered their own predecessors, who before had possessed that self-same land.

3.3. The Colonisation of Africa:

Our continent has gone through the same cycles of migration and displacement, including our southern region. A few examples: Arab conquest of the East Coast gave rise to the Swahili language as lingua franca across present-day Tanzania and Kenya. The migration of the Bantu peoples from the equatorial regions southward, systematically displaced the Khoi and the San of Southern Africa, forcing them into the south-western parts of the sub-continent.

In some places this latter migration was reversed, such as that of the Damara of Namibia (a tribe originally from the equatorial forests who had migrated south to eventually populate most of the central and northern parts of present-day Namibia, before they were subjugated by the Nama; their own tongue was thus replaced by the Nama language and most Daman ended up as servants in Nama (and later Herero) households.

It is generally accepted that the Khoi and San were the ab-original occupants of what is now South Africa, so that they would thus have the strongest claim to its land (if time-in-place would be the only norm). But who are the Khoi and San today? Their descendants are practically all part of “us” who speak Afrikaans – particularly that 60% of modern-day Afrikaans speakers who are not “white”.

European colonisation of Africa notoriously took no heed of the geographical footprints of tribes and drew borders arbitrarily. The introduction of Western-style economic activity in these multi-tribal territories quickly resulted in metropolitan conurbations springing up where-ever economic activity created employment opportunities.

These growth points attracted members of all tribes, causing these urban sprawls to be populated by a mix of peoples. Meaning that the old tribal lands largely lost their political relevance, since the vast majority of the populations of the new countries that eventually emerged, came to live in those shared urban areas, rather than in the erstwhile tribal lands. In the case of South Africa, this has resulted in more than two-thirds of the total populace living in the post WW2 era in these shared urban spaces, and no longer in traditional tribal homelands.

Realistically speaking, therefore, any constitutional model that tries to base itself in the historic pattern of geographical dispersion of tribes is without practical relevance for the great majority of the present-day urbanized populace. This is a point well illustrated by the case of us Afrikaans-speakers, who live spread out across practically all parts of present-day South Africa and Namibia, and preponderantly so in the urban areas.

(My sole objective with raising all this ethno-talk here is to say that, yes, tribal affiliation is worthy of being proud of and should be cherished as part of a rich diversity, but any debate about who now supposedly has the strongest historical claim to which piece of land is out of touch with reality. Similarly, efforts to try and base a constitutional model on past tribal footprints, was and remains a fool’s errand because it, too, is so clearly divorced from the present-day economic and demographic reality that pertains to the vast bulk of the population. This is not to say that the reality of ongoing identification of us all with our tribes can be simply ignored, such as in opting for a Westminster-style constitutional model which relies exclusively on protecting “individual rights”; modern Africa is replete with examples of where that inappropriate, Eurocentric model has caused pluralist states and societies to descend into internecine slaughter and destruction).

That said, let’s start now with The Story of Us.

3.4 The Old Cape:

The melting pot variously called the Cape of Good Hope or the Tavern of the Seas was definitely not institutionally or legally a race-based society – of that our DNA is proof enough!

The local inhabitants encountered there by the first European discoverers in the 15th century, were the Khoi (“Hottentot”) pastoralists. They themselves had originated far to the north, in East Africa, but had already been present in Southern Africa from about 2,000 years ago with their sheep and cattle. The other indigenous people were the San (“Bushmen”) hunter-gatherers.

The present-day so-called “coloured” population of South Africa are regarded by DNA researchers as the most mixed population on Earth, with on average up to 43% of their ancestry typically being Khoisan derived, up to 28% European, 11% Asian and between 20-36% Bantu. When looking specifically at the “mothers” and “fathers” of modern-day so-called coloureds, then some 60% of the maternal lineage is Khoisan derived, and 32.5% of the paternal lineage is of European origin.

There is much that distinguishes the colonial history of the forebears of us present-day Afrikaans-speakers, when compared to other colonial situations around the world. Looking at it from a national security perspective, not the least of this was our forebears’ fighting ability and excellence as tacticians (although, unfortunately, grand strategy was often a different kettle of fish…).

The first example of these skills in play against would-be European colonisers came in December 1509, when a fleet of three Portuguese ships under Francisco de Almeida anchored in Table Bay. After initial friendly trade with the local Goringhaiqua tribe, some Portuguese sailors tried to take advantage and were sent packing. The sailors then convinced Almeida that revenge was appropriate, so that a force of 150 Portuguese landed the next day to attack some 170 Khoi defenders. The latter astutely allowed the Europeans to approach their settlement, which was situated among thick bush, before attacking them. Effective use was made of their trained battle oxen.

The long and the short of it is that the Portuguese, although armed with steel and gunpowder, were thoroughly routed by their lesser armed opponents, thanks to the superior tactics of the Goringhaiqua. The Portuguese lost 64 men, among them Almeida himself, in what became known as the Batlle of Salt River. The result was that the Portuguese empire adopted a policy of avoiding the Cape, which allowed the Dutch, French and English a gap to take up trading with the locals.

Had Almeida been successful, the result could have been that the Cape would have become a state-run colony of a European crown, as in Angola or Mozambique. Some century and a half later, when the Dutch East India Company (the VOC) in 1652 established a replenishment post at the Cape for its passing ships, it was as a commercial trading enterprise that the VOC set up shop, and not as a crowned imperial power. The company, dedicated to making money, couldn’t care less about the racial or national origins of its workers, who were a merry mix.

The VOC decided to establish their replenishment station at the Cape, largely due to the positive report received in 1649 from the survivors of the VOC ship Haarlem which had been shipwrecked at Bloubergstrand in 1647. The survivors had painted a very positive picture about friendly relations with the local Khoi (nowadays also referred to as Khoekhoen). At that stage, amicable contact between passing Europeans and the indigenous tribes at the Cape had become commonplace, with one of the local Goringhaiqua chiefs, Autshumato (“Harry the Strandloper”) who had voyaged to Bantam on the island of Java in 1630, where he had been taught English and Dutch, so that he could act as interpreter. By all accounts, he became quite wealthy upon his return to the Cape, acting as “postmaster” for passing ships and facilitating trade.

By 1707 already a young Hendrik Biebouw became the first known person of European extraction at the Cape to have formally identified himself with the statement that “I am an Afrikaner” (as distinguished from being a European). This rapid identification with their new continent, leaving the old behind, was one of the most important of those “fork in the road” choices that Afrikaners made very early on. This was no doubt aided by the fact that theirs was not some crown colony, but a new land which they, that merry mix, were essentially developing themselves. The VOC had rendered minimal assistance, so as to keep costs down for the company. Defence, for example, was based upon the “Free Burghers” (meaning, as distinguished from company employees), who had to provide their own horse and gun, receiving only powder and shot from the VOC, who thus maintained only “kruithuise” (gunpowder stores) and not garrisons of troops in the towns that were springing up, such as in Stellenbosch.

A disastrous consequence of the VOC settlement was the introduction of smallpox. This devastated the Khoi population in 1713, causing many of the limited numbers who survived to flee the vicinity of the Cape settlement, trekking North.

The church in the days of the Old Cape was also free of notions of racial segregation. It served as the effective “Home Affairs” department of the local VOC company administration, conducting marriages and registering births and deaths. As far as marriage was concerned, the church’s only requirement was that a free man may not marry his slave – she first had to be manumitted. Nothing about race.

The upshot was that Cape society was essentially divided by class, between those who were “churched” and those others who weren’t bothering and just lived informally together. That this latter “lower class” consisted mostly of people of colour cannot be denied, but among the “upper class” a significant number of people of colour also featured. These were freed slaves (mostly successful tradesmen of Malay origin) and former slave women who had married “free burghers” and became proprietors of some of the most successful farming estates around Stellenbosch, Franschhoek and the Drakenstein – the “stam-moeders” of many a leading “white” Afrikaans family of today.

Perhaps the best-known governors of the Old Cape, the widely respected Simon van der Stel (after whom Stellenbosch was named) and his less-appreciated son Willem Adriaan, would under Apartheid criteria have been classified as so-called “Coloureds”.

3.5. Adam Tas and Race as a Political Weapon:

The first overtly political “fork in the road” regarding what role (if any) race should formally play at the Cape was encountered after a new arrival from the Netherlands, Adam Tas, settled at the Cape in 1697 at the age of 29. Tas became secretary of a Free Burgher organisation known as the “Brotherhood” (amen!) which initially protested against two things: that VOC company officials acquired for themselves the best farmland, and that the VOC guarded a monopoly on trading with passing ships. The Brotherhood convinced 63 of the some 550 Free Burghers of the time to sign a petition against Willem Adriaan van der Stel, which was surreptitiously sent to the VOC in Holland in 1706. Willem Adriaan was recalled, and company officials were subsequently prohibited from owning land.

This part of Tas’s political activities is generally known to this day and lauded. However, what is not common knowledge, is that Tas went on from this to launch a vitriolic campaign in which he advocated that race (i.e., skin colour) should be formally recognised as the distinguishing norm in terms of which society at the Cape should the formally structured. He openly disparaged people of colour in his writings and speeches.

Tas thus was one of the main initial planters of the seeds of the race-based political ideology that came to dominate South Africa in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, in his time he could not sway the likes of the church, the VOC, or the bulk of the population. (This was, unfortunately, later to change thanks to the impetus for his kind of thinking brought by the arrival of the race-conscious British and the introduction of the race-based norms and practices that they had made commonplace in their other colonies around the world).

3.6 The Cape Malays and Written Afrikaans:

Important for the development of the Afrikaans language was the banishment to the Cape of leading individuals from the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) known commonly as the Malays. These were educated people, adherents to the Muslim faith, and thus familiar with the Arabic alphabet. They were the first to use Afrikaans as medium of instruction in their schools. The oldest written texts in Afrikaans (written in Arabic script, not the Roman one) date from this time. Equally, they piloted the first books printed in Afrikaans – again, using Arabic script. The Holy Koran was translated into Afrikaans well before the Bible was.

3.7. Republicanism:

The American and especially the French revolution did not pass by the inhabitants of the Cape unnoticed. By the late eighteenth century, they were fed-up with the VOC’s corporatist, profit-focused administration, where no one had an effective vote – no matter your skin colour or social class. The consequence was that, by 1795, the burghers of the Graaff-Reinet district, followed by those of Swellendam, declared republics, kicking out the local VOC officials.

3.8. First British Occupation:

But then came the British – the first occupation, which lasted from 1796 to 1802. This was a strategic move in the context of the Napoleonic wars, seen therefore as temporary. It had as goal to prevent the Cape, with its strategic location on the important sea route to the East, from falling into French hands. Being perceived as a temporary measure, the British interim administrators did not then make fundamental changes.

3.9. The Batavian Republic – Africa’s First Non-Racial Democracy:

A very significant and influential period then followed at the Cape, even though short-lived (1802-1806). This was the reign of the Batavian Republic (during the Napoleonic era), inspired by the same French revolutionary ideals that had so appealed to the burghers of Graaf-Reinet and Swellendam. The Batavian Republic brought into being at the Cape, the first non-racial democracy on African soil.

The Cape was no longer run by a company, but by a modern state that accorded voting rights to all qualifying adult males, no matter their skin colour. Religious freedom was for the first time ordained (especially important to the Muslim Malay population of the Cape). Furthermore, the institution of slavery was officially curtailed and designated for total abolition – all children of slaves were henceforth born free, and the importation of new slaves was prohibited, so that this abhorrent practice was destined to come to a natural end with the existing generation.

The Afrikaans-speaking population of the Cape were now united in their destiny, which explains why the British found at the 1806 Battle of Bloubergstrand (the 2nd British invasion and occupation) that, even though the regiment of rented European soldiers, the Waldeckers, ran away at the first shots, fierce resistance was offered by the three local units. There were the Hottentot Light Infantry, together with the Swellendam Dragoons (the burghers who rode in from the interior on horseback) and the Javanese Artillery Corps (the latter being the volunteer Cape Malay freemen who manned the Castle batteries and provided the field artillery).

An alliance of local fighting men bound together by love of the same land and by speaking the same language, Afrikaans.

3.10. The Second British Occupation:

The 2nd British occupation meant that all the humanist and democratic Batavian principles were immediately suppressed.

Confronted by a largely hostile Afrikaans-speaking population, the British immediately resorted to their tried and tested recipe of divide-and-rule. For example, they actually tried (unsuccessfully, of course) to get the burghers on their side by promising to re-institute slavery in all its ugly dimensions, whilst at the same time working to polarize the “coloured” population against their lighter-skinned compatriots. (The etiquette of “Coloured” was a British import – in Afrikaans, the people that the British called “Coloured” had been referred to in terms of their tribal origins, such as Bushmen, Hottentot, Griqua, Malay, and the like).

3.11. Trekking:

Trekking northward, away from the reach of the authorities at the Cape, was already a time-honoured custom among locals even before the Great Trek. It was actually mostly initiated by our “non-white” forebears like the Basters, Oorlam, the Namas and Griquas, who trekked towards the empty spaces of the North-West and up into present-day Namibia, founding settlements such as Windhoek. The latter town, now the capital and only city in Namibia was founded in 1840 by the Oorlam chief Jonker Afrikaner, who had moved into Namibia from the Northern Cape already in 1796. Jonker Afrikaner had erected a stone church that could accommodate 500-600 people in what is now the suburb of Klein Windhoek.

The Afrikaans-speaking Oorlam, who were originally from the vicinity of Tulbagh in the Boland, Western Cape, and were of mixed Hottentot, white and slave blood, soon dominated central Namibia.

The story of how and why the Oorlam had crossed the Orange (Gariep) River into South-West Africa in 1796, has a direct bearing on my own family. The Oorlam were fleeing the Northern Cape after having murdered the family of Petrus (Pieter) Pienaar, who was the local Veldwachtmeester. The Oorlam had moved with Pienaar to his farm Groot Toorn in the Hantam in 1790, where they formed a kind of militia in the part-time employ of the VOC and directed by Pienaar, operating against marauding Bushmen and other cattle rustlers (and probably appropriating cattle themselves).

By 1796 their relationship had soured, however, leading to an altercation on the steps of Pienaar’s homestead in which Pienaar was shot by Jonker’s brother Titus, and Pienaar’s family then all murdered (or so Jonker and his band thought – they had decamped north pretty fast).

Two of Pienaar’s children in fact survived the massacre, being his young daughter Mieta and son Jacob, who had both been knocked unconscious with gun butts and left for dead. They were saved by a courageous young Bushman woman, who had revived Mieta and the two of them had then dragged Jacob into hiding in a reed-bed next to a nearby stream. Mieta Pienaar would eventually marry one of my Steenkamp forebears, thus becoming my great-great-great grandmother.

The Great Trek of the 1830s, going north-east, was also not race-based. Its main proponent (who first went up to explore Natal and then wrote and published the printed tracts promoting the idea of escaping British rule by trekking to Natal), was a well-educated and respected “coloured”, Jan Bantjes. He would become the official secretary of the Trek (kind of the like the chief counsellor of the leader) and later the secretary of the Transvaal Volksraad, as well as the ZAR’s postmaster general.

Jan Bantjes was not the only Trekker of colour – some 40% of those killed at Blaauwkrantz and Weenen were Afrikaans-speakers of colour, and a large contingent were intermingled as part of the commando that fought at Blood River.

Great Trek secretary Jan Gerritze Bantjes (credit: SA History Online)

British “spin” does not admit to the reality that those who trekked out of the Cape Colony, did so because they did not wish to live under benevolent British imperial rule. It is regularly suggested in English-language sources that the Trekkers left the Cape because of the abolition of slavery by the British. This is nonsense, as is proved by the fact that the Afrikaans republics subsequently established in the interior by the Trekkers on the Batavian model, did not re-institute slavery – what really had annoyed the burghers in the Cape who had owned slaves, was the fact that the British had originally promised to pay them compensation but then, after the fact, had stipulated that it had to be collected in London!

The British abolition of slavery in any event had been accompanied by an edict that freed slaves were obliged to subsequently contract themselves as indentured servants – thus, a question of semantics?

Furthermore, although there were of course committed British abolitionists who had campaigned for the measure on moral grounds, the true impetus behind it had in the early 1830s come from British owners of sugar plantations in the Caribbean, who had faced financial ruin at the end of the Napoleonic wars when normal trade in sugar resumed and they sat with a surplus of slaves to maintain. These Caribbean plantation owners (known as “planters”) were powerfully represented in the British parliament and overnight became the lead backers of freeing the slaves and especially of paying compensation to former owners. This, according to recent research published by the BBC and University College London.

See this telling quote from The Guardian newspaper: “The compensation of Britain’s 46,000 slave owners was the largest bailout in British history until the bailout of the banks in 2009. Not only did the slaves receive nothing, under another clause of the act they were compelled to provide 45 hours of unpaid labour each week for their former masters, for a further four years after their supposed liberation. In effect, the enslaved paid part of the bill for their own manumission”.

3.12 Republiek Natalia – No getting away from the British:

No sooner had the Trekkers established the Natalia Republic, when the British arrived there to annex that as well. So that the Afrikaners packed up and trekked back over the Drakensberg mountains, to what became the Orange Free State and South African (ZAR / Transvaal) republics.

3.13 Adopting Afrikaans:

One of the most important “forks” in the road to new nationhood, and one of our best and most distinguishing choices (which sets us apart from those who had colonised other parts of the world) was when the “white” Afrikaans-speakers at the Cape began to ditch the Dutch language in favour of recognising our mother tongue as a proper language in its own right – not a “kitchen dialect” spoken by the “non-whites”. The Quebecois in Canada still speak and write French, the Brazilians speak Portuguese, and Spanish has endured in their ex-colonies, as did English in theirs.

Afrikaners are thus the only descendants of European colonists who came to proudly adopt an indigenous language as their own. This movement in favour of Afrikaans, from the white side, was driven (from around the 1870’s) by the activist brothers SJ & DF du Toit, Arnoldus Pannevis and CP Hoogenhout, who launched the Fellowship of Real Afrikaners (i.e., if you were a real Afrikaner, and not just geographically so, you cherished Afrikaans as your language, and not Dutch).

The Fellowship was founded in 1875, and it started publishing its own newspaper, the Afrikaanse Patriot, in 1876 (this initiative was not without opposition, as demonstrated by JH Hofmeyer launching an association in 1878 to promote the Dutch language; history shows, however, that Afrikaans won out).

As explained earlier, the Cape Malay community had all the while continued promoting Afrikaans, having been the first to publish books printed in Afrikaans, and translating their Holy Koran into Afrikaans well before the Bible was.

3.14 The Church turns Racist:

Another fork in the road was reached in the mid-nineteenth century. The decisions then taken by the Dutch Reformed Church had hugely negative consequences in the long term – especially for how white Afrikaans-speakers were to be perceived by other races (due to the close identification between the DRC and white Afrikaners).

At that time, despite two centuries of integrated worship at the Cape, a majority in the socially highly opinion-formative Dutch Reformed Church increasingly pushed for the segregationist positions that Adam Tas had lit the fuse for, and which corresponded to the attitudes on race encountered at the time in the other Anglophone colonies and in the USA.

In 1863 black Africans were excluded from DRC congregations and consigned to their own “sister church”, and in 1881 the same was done with regard to DRC members of “Coloured” appearance. This, despite strong resistance from many DRC theologians and parish ministers, such as in the Franschhoek congregation.

It was only in the mid-1980s that the DRC formally condemned racism, and then declared Apartheid a sin in 1990.

3.15 The Curse of Resource Wealth – here come the British again!:

The discovery of diamonds in the Free State resulted in the British annexing its western portion (around Kimberley).

The rapid rise of Germany as an aspiring colonial empire caused the British to invade and conquer Zululand (to ensure that the entire coast was locked up). For good measure, they decided to formally annex the ZAR as well. This latter deed did not sit well with the Transvaalers; after their delegations could not sway the British, the First Anglo-Boer War resulted.

To the surprise of the British, these “fighting farmers” knew a thing or two about tactics and shooting straight, so that they inflicted a number of defeats upon the British forces culminating in the Battle of Majuba Mountain. There the “Boers” (as they had by then become known) showed tremendous valour and skill to scale the mountain under fire and pluck the Brits off the summit.

The dusty Highveld savannah didn’t seem then to London to be worth all the bother, so that peace was agreed, restoring self-governance but under British “suzerainty” (the latter, to allow the British to ward off any German advances).

Very soon there-after, a vast gold reef was discovered on the Witwatersrand (by the prospector son of the self-same Jan Gerritze Bantjes who had helped initiate the Great Trek). And, again came the English – first as miners and magnates, and then as a private invading army (the Jameson raid, sponsored by then Cape premier Cecil John Rhodes; the Raiders soon met their come-uppance when they ran into the alerted Boer commandos).

Finally, the arch-imperialist Lord Milner was sent as governor to the Cape, charged with ensuring that the Transvaal be brought under full British control, by force of arms if need be.

This is how the British National Army Museum in London itself describes the causes of the war: “The origins of the Boer War lay in Britain’s desire to unite the British South African territories of Cape Colony and Natal with the Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic … The Boers, Afrikaans-speaking farmers, wanted to maintain their independence.

“The discovery of gold in the South African Republic (SAR) in 1886 raised the stakes. A large influx of English-speaking people, called Uitlanders (literally ‘Outlanders’) by the Afrikaners, were attracted by the goldfields. This worried the Boers, who saw them as a threat to their way of life.

“The Jameson Raid of 1896 was an attempt to create an uprising among the Uitlanders in the SAR. Led by Dr Leander Starr Jameson and his British South Africa Company troops, its failure was a humiliation for Britain and the supporters of confederation. It led to a further deterioration of the relationship between the British and Boer governments.

“Anxious to overcome this set-back and to give the British policy fresh impetus, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain appointed an outspoken imperialist, Sir Alfred Milner, as High Commissioner for South Africa in 1897.