Part 2: The Red Flag, by Henning van Aswegen. Abstract: The CPSA, Communist Party of South Africa, Communism in South Africa, Marxism, Trotskyism, Leninism, Socialism, Stalinism.

Following the introduction of Vladimir Il’ich Lenin to our story, the growth of Communism in South Africa took a turn for the worse in 1919 when a group of striking municipal workers led by J.T. Bain, used violence and force to usurp a Johannesburg City Council meeting. Bain and his Communist comrades ruled Johannesburg for a few days by means of a worker’s “soviet” – a cell in the Russian language. The Union Jack was lowered and replaced by The Red Flag and sounds of the Internationale droned through the Council building.

Fearing more violence and the loss of life, bewildered Johannesburg City Councillors and government officials surrendered unconditionally to the Communists’ threats and terms. News of the Johannesburg mini-revolution spread like wildfire, and for a while J.T. Bain and his extremist Johannesburg Communist League (JCL) comrades were the toast of South Africa’s working classes (also known as proletarians).

Under one Red Flag

After the First Congress of the Third International in Moscow in 1919 and the Johannesburg mini-revolution, the South African chapter of the International Socialist League was galvanised into action. In 1920 in Cape Town, the ISL and the JCL joined forces to form the embryo of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). The JCL’s application to join the Third International was rejected because the ISL’s application was already accepted, leading to the formal amalgamation of the two groups during the CPSA founding meeting in Johannesburg. During July 1920 the Third International issued a 21-point policy declaration, declaring that the CPSA would be the only representative group of the South African proletariat. Groups like the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), the Jewish Socialist Society (JSS), the Durban Maexis, Club (DMC), the Cape Communist Party (CCP) and the ISL quickly disbanded to join the new Communist Party of South Africa.

At the foundation congress of the CPSA on July 29, 1921, the following communists were elected to the Politburo: C.B. Tyler (Chairperson), Bill Andrews (Secretary General), S.P. Bunting (Treasurer), G. Arnold, Rebecca Bunting, T. Chapman, J den Bakker, R. Geldblum, A.Goldblum, H. Les, E.M. Pincus and R. Rabb.

A Violent Confrontation

The newly elected Politburo of the CPSA immediately became involved in the explosive mineworkers and labour situation in the Witwatersrand Mines. The CPSA correctly analysed the labour unrest as a potentially revolutionary situation. If they executed the mandate of the Third International skillfully, a general strike could instigate and lead to a Communist take-over of South Africa. There were other contributory factors to the labour unrest on South Africa’s mines in 1922, inter alia a worldwide economic recession, groups of disgruntled ex-servicemen and soldiers from the First World War who could not find work in the mines, and efforts by the mine magnates and owners to make their mines more profitable by replacing white labourers with black unskilled labourers.

Casus Belli of the 1922 Miniworkers’ Strike

Attempts by the mining magnates to increase the profit lines of their mines was tantamount to “waving a red flag in front of the proletariat,” according to the CPSA and this issue became the casus belli of the 1922 communist-inspired Mineworkers’ Strike. Their casus belli however was not a casus fortuitus because the terminology of the CPSA’s rallying banners was badly chosen. Rallying around the banners “Workers of the World Unite,” and “Keep South Africa White” opened the way for criticism of the CPSA that they were racists. The slogans of the CPSA belied the fact that they were striking in support of the proletarian masses, except for the black proletarian masses. 22000 Mineworkers nevertheless responded to the CPSA’s rallying cries and came out on strike on 10 January 1922.

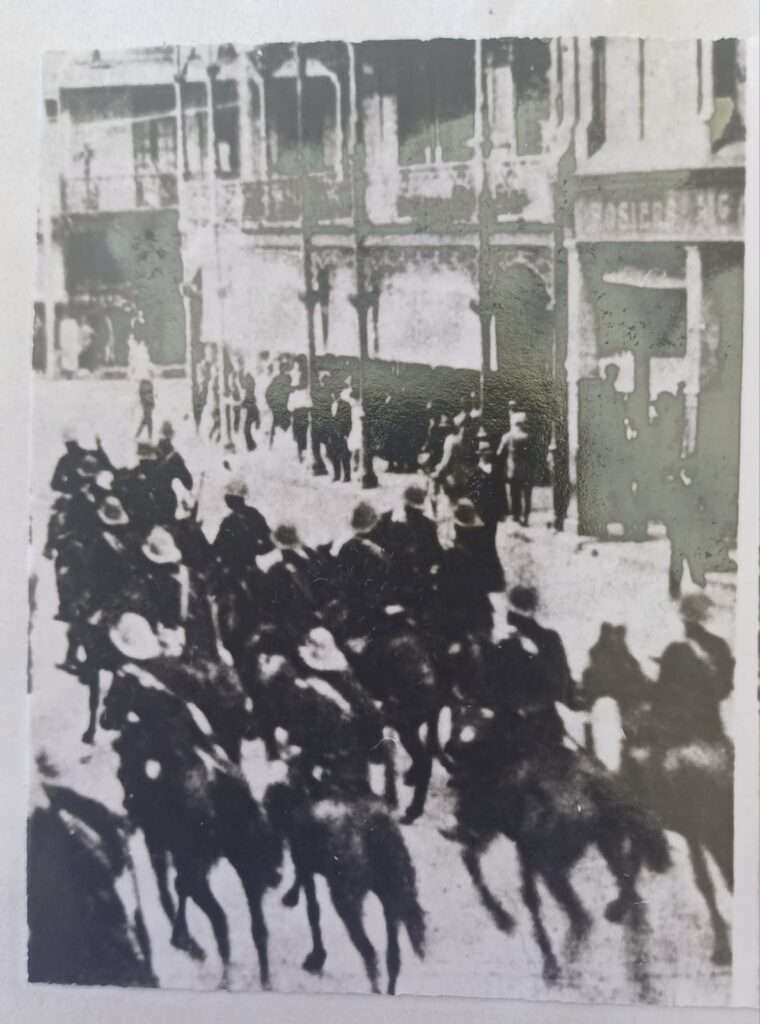

Cover photo: Mineworkers remove the bodies of strikers wounded in the 1922 Mineworker’s Strike. In this rare and unique photograph, the government deployed the SA Military Cavalry to quell labour unrest and violent clashes between rival groups.