ABSTRACT: Second extract from NONGQAI’s eBook on the South African Police Security Branch and the armed struggle launched by the SACP/ANC-alliance. This episode highlights the very limited scale of the conflict when compared to other such conflicts that raged in many other parts of the world during the Cold War. It explains the true nature of this armed struggle, which was simply armed propaganda, without any serious ability nor hope to overthrow the white South African state militarily. Finally, it explains the legal norms and system under which the SAP-SB detectives operated, which was akin to the British system as employed during the Northern Irish Troubles, and not at all similar to the Dirty War tactics sponsored by the USA in Latin America.

KEYWORDS: South African Police Security Branch (SAP-SB); SACP/ANC-Alliance, uMkhonto weSizwe; Nelson Mandela; armed struggle; armed propaganda

AUTHORS: Brig (ret) HB Heymans & Dr WP Steenkamp

SA’s ARMED CONFLICT: NATURE AND COMPARATIVE SCALE

(Episode 2 extracted from our e-Book on the SAP-SB vs the SACP/ANC)

2.1 The nature of the conflict: it was first and foremost armed propaganda.

Allister Sparks, in his: Tomorrow is Another Country, says that Nelson Mandela had told him: “I started Umkhonto We Sizwe … but I never had any illusions that we could win a military victory; its purpose was to focus attention on the resistance movement.”

The ANC’s “armed struggle” was classical armed propaganda – what was called in the 19th century (particularly in France) “propaganda by deed”. Or, as Brian Jenkins later stated: “terrorism is theatre”.

The O’Malley Archives housed at the Nelson Mandela Foundation covers the evolution of the ANC’s struggle. In Chapter 5, titled: Armed Propaganda and Non-Collaboration, it is explained that, in the course of the ANC’s 1978 – 79 internal strategic review, Vietnamese revolutionaries had introduced the ANC to armed propaganda as a formal concept, which the ANC then seized upon.

Revolutionary or armed propaganda typically has different, complimentary focal points. One such is “atrocity propaganda” (aimed at winning the moral high ground in the opinion of domestic and international audiences). Another is “disarming propaganda”, which Maurice Tugwell described in the Spring 1986 edition of Conflict Quarterly as: “Here the aim is to discredit and destroy any method, individual, police or military unit, weapon or policy that, because of its potential effectiveness, threatens the terrorists’ integrity and freedom of action. …disarming themes are often argued within the norms of conventional morality. Consequently, fronts are extensively used, and they appear to advance their causes pro bono publico…”

As will be shown when we deal in detail with the doctrines of the protagonists, the asymmetrical struggle against the overwhelming might of the white South African state’s security forces was first and foremost a propaganda-driven struggle for local and international opinion. In it, “atrocity propaganda” and “disarming propaganda” were key elements, which – fortunately for the revolutionaries – could play into a favourable (English-language) media environment locally and internationally and could also count on the support of Cold War era leftist pressure groups that had been established in Western countries by Moscow, the ANC’s main international ally and ideological fountainhead.

The reality that the conflict was dominated by propaganda is therefore highly signficant, when one assesses how it came about that the SAP-SB (as the ANC’s major institutional stumbling block) acquired such a negative public image among readers of the English-language media – very much distinct from the highly positive image created for readers of the Afrikaans media.

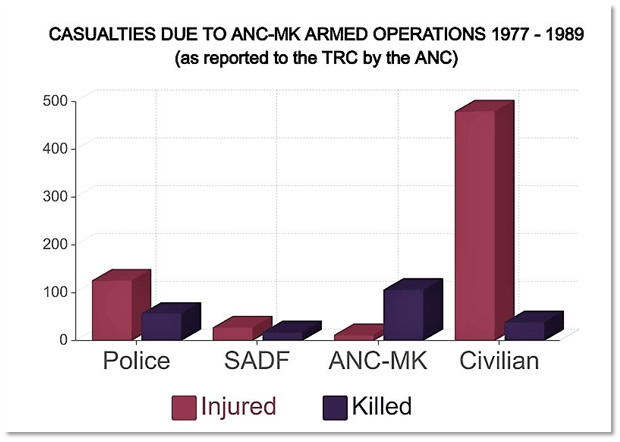

2.2 Being armed propaganda, statistically the scale of SA’s conflict was small.

The first table below illustrates the relatively small scale of South Africa’s internal conflict, when compared to other such conflicts of the 20th century. The casualty figures are actually remarkably low (when compared to the truly terrible popular impression almost of genocide, created by years of local and international media hype). Especially when considering that the conflict lasted some three and a half decades – but even more so when taking into account that, of the total number of deaths, three-quarters occurred as a consequence of the black-on-black power struggle over the last five years of the conflict as dating from the liberation of future president Nelson Mandela in 1990, to the establishment of the first elected non-racial government.

| COUNTRY / IDEOLOGY | ESTIMATED NUMBER OF DEATHS | % of POPULATION |

| Communist dictatorships (world) | 60,000,000 – 147,000,000 | ? |

| Nazi extermination Jews WW2 | 6,000,000+ | 68% |

| Cambodia (Pol Pot) | 2,400,000 | 33,3% |

| ZAR / OFS 2nd Anglo-Boer War | 42,000 (incl. 28,000 women / children dead in British concentration camps) | 15% of total Boers and 50% of Boer children |

| Rwanda (Hutu / Tutsi) | 800,000 | 10% |

| Chechnya (Russian Federation) | 90,000 | 8,2% |

| Guatemala (Central America) | 200,000 | 5,3% |

| Bosnia (ex Yugoslavia) | 200,000 | 5% |

| Algeria (independence France) | 300,000 | 3% |

| Rhodesia / Zimbabwe | 60,000 | 0,83% |

| South Africa (1960 – 1994) | 20,500 | 0,05% |

The next table objectively shows the small number of all-cause deaths (in other words, also natural causes) that occurred in SAP-SB detention from 1960 to 1990, as compared to deaths in similar situations around the world during that same time period – including in so-called first world Western countries. It very clearly shows that the SAP-SB took particular care to try and avoid deaths, since they knew full well that this was first and foremost a propaganda war in which any death from any cause whatsoever, would be seized upon as ammunition aganst them.

|

ALL-CAUSE DEATHS IN DETENTION |

TIME SPAN |

WHERE AND WHO |

|

50,000 Killed Dirty War: “Plan Condor” |

Cold War |

S. America (+30,000 “disappeared”) |

|

11,000 inmates and police detainees |

2005 – 2020 |

State of Texas (total pop = ½ of S.A.) |

|

900 +- admitted to by ANC in its camps |

1960 – 1990 |

ANC cadres died outside S. Africa |

|

672 “Necklace” of opponents of UDF |

1984 – 1987 |

Burned alive extra-judicially S. Africa |

|

474 Aboriginal deaths in detention |

1960 – 1990 |

Australia |

|

214 Deaths in police detention |

year 2019 only |

South Africa, custody of new SAPS |

|

800+ Black policemen assassinated |

1990 – 1994 |

South Africa, mostly by ANC/UDF |

|

67 all causes, in SAP-SB detention |

1960 – 1990 |

South Africa |

2.3 The demographic and geographic impact of the conflict was also small

The limited demographic impact of the internal political power struggle (i.e., what percentage of the different population groups actively took part in, or even took sides) as well as the restricted geographic distribution of the civil unrest, are both important further indicators of the relatively limited scale of South Africa’s internal conflict. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) undertook a detailed investigation, after the conflict. This important study, titled: Country Report South Africa (1999), provides significant data that helps one to better understand the nature of the conflict and its (rather limited) scope. The ICRC assembled representative focus groups of members of the public, from which reliable extrapolations could be made, reflective of the public at large.

This ICRC study shows that only 34% of the black population had actually even in their minds taken one or other side in the conflict between the white government and the liberation movements. Furthermore, only 3% of blacks had regarded themselves as having been actively involved as actual “combatants” in what had been portrayed by the ANC as having been a popular “people’s war”. Only 33% of blacks reported living near to an area where conflict had actually occurred (with even that level only being reached during the latter, black-on-black phase of the struggle for political power).

The ICRC investigation also shows that the civilian population, particularly blacks in conflict areas, experienced a marked increase in violence when the power struggle shifted to black-on-black: “For a large number of the participants in the consultation, the political violence among black South Africans was even more vividly horrifying than the struggle against the white regime. Participants in the consultation, many of whom were active in this later stage of the conflict, recall that this violence often included the shooting of women and children, rape, burning or bulldozing of buildings with civilians inside, and the infamous “necklacings” – placing a tyre around the neck of an opponent, filling it with gasoline (petrol), and setting it on fire. The comments of participants in the focus groups and in-depth interviews suggest that in these and other ways the limits broke down in the township clashes in a way that was both horrifying and bewildering.”

The findings of the ICRC correlate well with other surveys done at the time, which for example indicated that nearly four in ten blacks in 1992 said that they placed their trust in then-president FW de Klerk. It is thus evident that, contrary to the impression created in the media, the South African internal conflict was in fact rather limited in scope: in terms of comparative statistics, demographic impact and geographical footprint (which explains in part why – to the surprise of many international observers – a negotiated settlement could be reached among South Africans themselves, without needing to follow the example of the ex-Portuguese colonies, Rhodesia, and Namibia where talks were held outside the respective countries, under foreign auspices, only after bloody guerrilla wars).

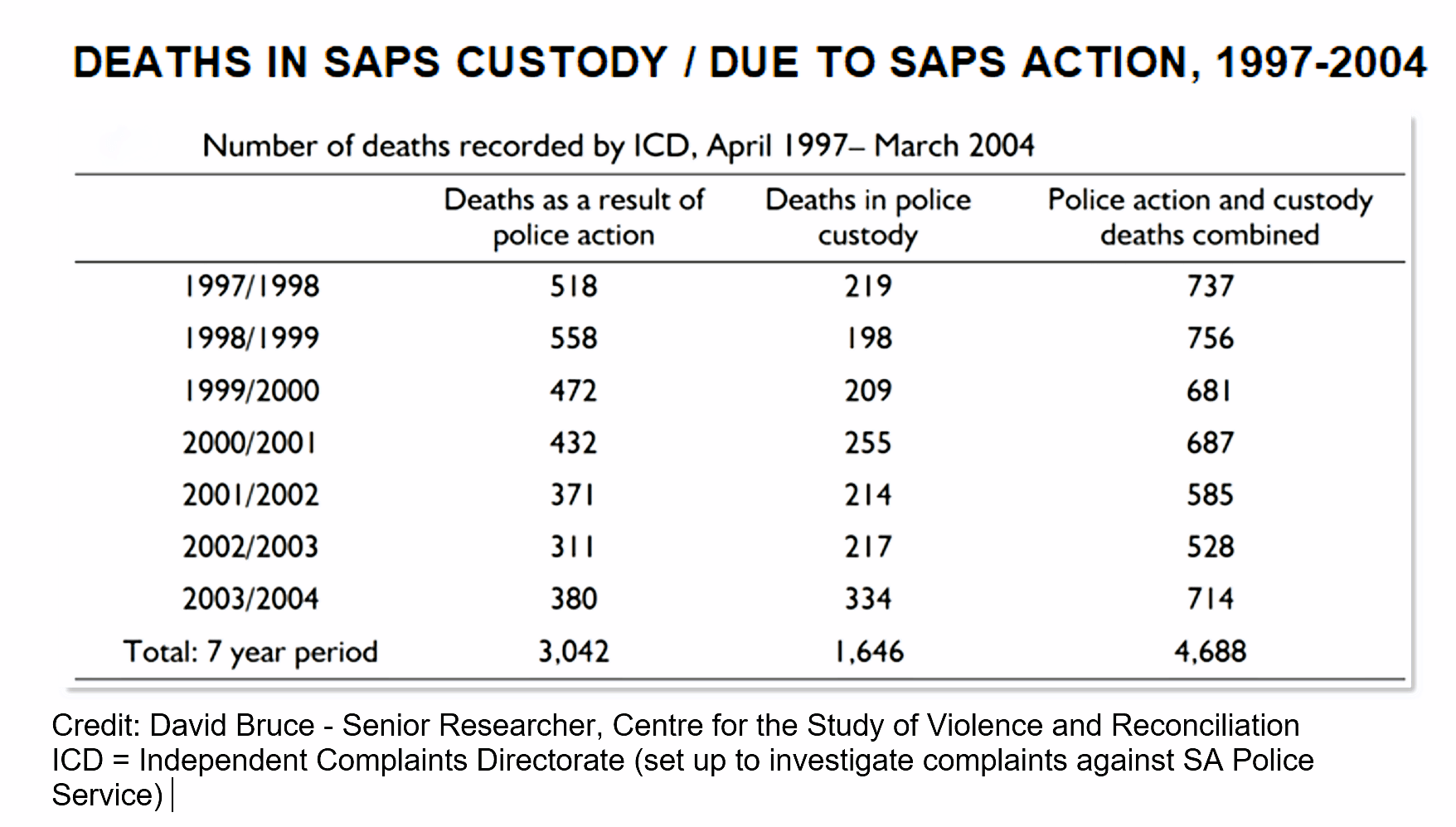

The next table shows deaths due to the SAPS (the new police service that succeeded the SAP) in a South Africa at peace with itself after the installation of a majority Black government dedicated to the protection of human rights. This is a particularly valid basis of comparison (since it relates to the same country) enabling one to appreciate the care that the SAP-SB had bestowed on security detainees during a period of armed conflict.

2.4 The nature of the conflict from a constitutional and jurisprudential perspective

The security or special branch of the South African Police was formed in June 1939, less than three months prior to the outbreak of the 2nd World War. It was modelled on the Special Branch of the London Metropolitan Police (Scotland Yard), but had a country-wide remit, since the South African Police was by law the national police force of the entire Union of South Africa.

The SAP-SB was thus the constitutionally ordained national law enforcement body focused on investigating internationally-recognized crimes against the peaceful constitutional order (meaning essentially, the illegal furthering of political aims by violent means such as terror or armed insurrection).

The unit was created and first served to counter radical internal opposition against South Africa’s war effort against Nazi Germany during the Second World War (when 6,636 opponents of South Africa’s participation in that war were detained without trial in concentration camps). Subsequent to the 1961 conversion of the Union into the Republic of South Africa, the SAP-SB seamlessly carried on serving the Republic (when the latter was still white-ruled, and at the time confronted by the Cold War threat that emanated from the communist powers).

During WW2, many Afrikaners were sceptical of the SAP-SB because of the internment without trial of pro-independence Afrikaner activists such as future prime minister John Vorster. The English media, however, at that stage lauded the SB (which happened then already to have been under the command of an Afrikaner). The roles inverted after the 1948 white elections, when the Afrikaner Nationalists took power – from that point on, the SAP-SB (and the government it was now identified with) was portrayed by the local English-language media as racist Afrikaner nationalist oppressors.

Nongqai magazine's series of extracts from eBook on the armed struggle between the South African Police Security Branch and the alliance between the SA Communist Party and the ANC / MK

Objectively seen in terms of the constitution, the SAP-SB as institution was NOT a tool of any one white political party, and it certainly didn’t make the laws of the land. Just as any police force anywhere, its function was to uphold the law “as is”, i.e., as constitutionally made by the legislature. As elsewhere, it did this under the policy direction of the Executive (cabinet). No police officer – nowhere in the world – has the luxury, nor the right, to pick-and-choose which duly-made laws he or she by personal preference wants to enforce.

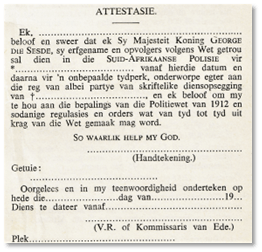

Above is a copy of the attestation as a police officer that my father and all other new members of the Force had signed under oath upon entering into the Union of South Africa’s police force.

In English it reads that: I, XXX, promise and swear that I will faithfully serve His Majesty King George the Sixth, his heirs and successors, in the South African Police in accordance with the Law … and I promise to abide by the stipulations of the Police Act of 1912 and such regulations as may from time to time be promulgated in terms of the Law.

Nongqai magazine's series of extracts from eBook on the armed struggle between the South African Police Security Branch and the alliance between the SA Communist Party and the ANC / MK

The Mission Statement of the “Apartheid” South African Police force is also revealing: It stressed impartiality and observance at all times of the law and societal norms, aiming to serve with efficiency and accountably, the country and all of its residents. In full, it reads as follows:

“Mission of the South African Police

We undertake, impartially and with respect for the laws and norms of society, to protect the interests of the country and everyone therein against any criminal violation, through efficient service rendered in an accountable manner.”

It should be noted that, at least as far as its white population was concerned, the Union and pre-1994 Republic constituted a full-blown Western democracy, with an independent judiciary, highly confrontational parliament to which ministers were accountable, and a largely independent, vocal and inquisitive press. The SAP-SB officers were thus well aware of the reality that their every action would be publicly scrutinized in particularly the English-language section of the local media which was politically hostile to the Afrikaner nationalist government, as well as by means of unrelenting parliamentary questions. The police knew that decisions about the innocence or guilt of suspected “terrorists” were not theirs to make. It would and should be determined by the courts in open session, with the accused deemed innocent till proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt and also benefiting from top legal representation (usually paid for from abroad).

The institutional function of the SAP-SB detectives was to investigate alleged crimes against the constitutional order, gather relevant evidence and then present this to the prosecuting authority, who would decide whether and for what to charge and prosecute the accused in open, everyday court (there were no “secret” or “state security” courts in Apartheid South Africa). It was in and by these courts, functioning openly under full public and media scrutiny, that guilt or innocence would be factually determined in terms of commonly-applicable rules of criminal procedure (as derived essentially from English law).

The legl system under which the SAP-SB functioned thus largely resembled the British approach in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. It was a far cry from, for example, the “Dirty War” tactics applied by the military dictatorships of Latin America during the Cold War, taught to them by the USA at the School of the Americas in the erstwhile Panama Canal Zone.

Yet, despite this adherence to fundmental norms and what the statistics have demonstrated about the actually very limited scale of the conflict, it was Apartheid that got labeled as a crime against humanity. As judgement on a overtly racist ideology, that label is justified. In reality, though, South Africa had simply found itself trapped on the rail tracks of history with the locomotive of time bearing down upon it unstopably (as Brezinzski had graphically warned) as being the last remaining remnant of white colonial rule in the world – and was duly castigated for a legacy of abhorent practices that had been commonplace across imperial domains, particularly of the Anglo-Saxon kind.

What in the end had set South Africa apart from the typical “fight-it-out” course that de-colonization had taken in places like Algeria, French Indo-China/Vietnam, and the former British, Belgian and Portuguese territories in Africa, was that the conflict in South Africa was in the end settled peacefully around the negotaition table (to the astonishment of the world – probably because of the Afrikaners’ own experience of British imperialism). In this the erstwhile Security Forces had vitally contributed – both by maintaining the necessary stability which enabled an orderly, negotiated transition, and by having demonstrated that there was no way in which radical elements from the left or the right would ever be allowed to impose their incendiary constititional dreams – whether that be of establishing a Marxist People’s Republlic, or a right-wing race-based dismemberment of the country.

TO SUM UP: quite contrary to the public perception created by a deft and intense propaganda campaign, the “armed struggle” initiated and waged by the SACP/ANC-alliance against the then South African state (which constitutionally the SAP-SB was duty-bound to investigate and counter, in order to maintain law-and-order and safecuard the populace against terror attacks):

- Was statistically miniscule compared to other similar conflicts waged elsewhere in the world in the 20th century;

- Affected a relatively limited geographical area of the country, and a quite small percentage of its population;

- By nature, this conflict was political and consisted of armed propaganda and violent intimidation of opponents, rather than a viable guerrilla campaign with any realistic hope of overthrowing the government by military means;

- This armed insurrection and intimidation by terror (such as the infamous “necklacing” of opponents) was essentially countered by a relatively small but elite Special Branch consisting only of around 3,000 top detectives who weren’t a law onto themselves, but who (like anywhere else) had to uphold the existing laws as ordained by the legislature, with the police functioning under the direction of cabinet and subject to the close scrutiny of the media and parliamentarians ever ready to pose probing questions; and

- Within a jurisprudential framework not of special “security courts”, but consisting of the SAP-SB presenting evidence-based cases for consideration by the prosecuting authority, for prosecution in the everyday open courts, according to the same normal rules of criminal procedure protecting the rights of every accused in the land charged with any common crime, such as fundamental universal rights like the presumption of innocence and the right to legal counsel.

As will later be seen, the above adherence to the safeguards of a courts-based jurisprudence stood in stark contrast to what pertained in the ANC’s own detention camps abroad regarding meting out “justice” to dissidents, or the “rights” accorded to political opponents who were hauled before “people’s courts” to then be necklaced…

TO BE CONTINUED…