CL Chandler : A MI 6 Spy?

ABSTRACT : The strange and exciting life of Mr CL Chandler, a possible secret agent of the British Government, in Russia especially during World War One. His activities after the war have aroused the suspicions of his family. It is very difficult to piece together the covert activities of a professional and competent spy. This article based on fact is a plausible explanation of his secret life.

KEYWORDS : gold, Petrograd, Brixton Prison, Chandler, Ernest Vivian, Chandler, Errol, Chandler: Clement Leslie, Pontybodkin, Cheka, Soviet Secret Police, Dickson John Gordon, Dollar Shipping Line, Warsaw, Giles CRB, HMS Lord Nelson, HMS Marlborough, Imperial Russian Army, MI 5, MI 6, Francis Cromie, Russian Czar, SS Susquehanna, The Chicago Tribune, Brest-Litovsk, Trew HF, Trieste, Union Castle Line, United States Navy, Rin-Tin-Tin, Vienna, Vladivostok, Port Elizabeth

AUTHOR : Errol Chandler

SOME HISTORY OF THE SECRET INTELLIGENCE SERVICE (MI 6)

Introduction and comments by Brig HB Heymans

I saw the following post on Facebook which immediately attracted my attention:

“My father travelled a lot on Union Castle ships, disguised as a crew member! He was with the British Secret Service, and they used to monitor the passengers and crew, checking who was travelling, who they met, and so on.

I have some of the crew lists that say he was on board either as a dining-room steward, or cabin steward, or bar steward, or baggage attendant etc. All positions in which he could be in contact with passengers and crew without appearing to be intrusive, hear their conversations, ferret out their intentions etc.

I guess, hiding in plain sight, would be the best description. In later years, he was based in Port Elizabeth, and he used to take my sister and me on board the two Union Castle ships that were there at weekends, one outbound from the UK, the other inbound. While he did whatever he was supposed to, he deposited us in the ship’s bakery where they fed us with cakes!

We only found out about his real job years after he died. So, cast your minds back, did you encounter a crew member who was friendly and full of questions?”

Further comments by Hennie Heymans

Judging the post on Facebook as “most credible” I immediately contacted Errol Chandler the man who posted the story on Facebook and who lives in the UK. Fortunately, he returned my message, and we started corresponding.

I have read various books on the history of MI5 and MI6, and I had studied the subject “intelligence” as part of my studies in National Security Studies. We, as part-time university students who were all members of the intelligence community in South Africa, were very fortunate to receive lectures by former MI5 and CIA officers. I was also acquainted with the history of Sydney Rilley and Bruce Lockhart who were active in Russia about a century ago. The last Chief Commissioner of the Colonial Natal Police, Col WJ Clarke, also served in Russia with the British Army. (He mentions in his autobiography – embargoed until 2028 – that he has taken an oath not to reveal any details of an operation he took part in, whilst in Russia.)

For many years I was stationed at Security Branch Headquarters, and I have studied many (Colonial) files on this subject. Yes, reading old files, I saw that there was contact between the Commissioner of the South African Police (SAP) and the Head of MI5 – After all these years I even remember the postal address and telegraphic address. There was a cordial relationship between the SAP and MI5 until South Africa became a republic (1961), then we became the “clients” of MI6. There were various sanctions imposed on South Africa – sport, weapons and cultural. One can say there was a state of professional hostility between the UK (MI6) and South Africa. Also, some South African agents were detained and/or questioned by British Intelligence.

During the “Cold War” (circa 1963) General HJ van den Bergh took command of the Security Police and he looked towards Washington and Bonn for help, training, and liaison. We also had close ties with Israel, Taiwan, and Chile.

We even “caught” two members of MI6 on spying charges regarding “sanctions busting” with Rhodesia and South Africa’s aircraft industry. We know that MI6 also played a great role as agent of change in South Africa post 1994 – just look who was decorated and why?

As an amateur historian I have a great respect for the intelligence services of the UK and the Royal Navy. I also remember in the years after Union (1910) the South African Police also copied Security Reports to the Admiral of the Royal Navy at Simonstown.

The British projected immense power through the Royal Navy, the foreign office (MI6 and diplomacy) and the home office (MI5 and Scotland Yard) all over the globe. I think that Mr Chandler when working on Union Castle ships was in the employ of MI5 (Security Service).

Gold and the First World War

Lt-Col HF Trew wrote as follows on £14 million of bullion sent to the UK:

“One day I went into the Civil Service Club, and there to my surprise, met Captain Giles of the South African Police. He told me that during the rebellion no gold had been sent away from the Rand. He had come down with two armoured trains and a police guard escorting about £14,000,000 of gold, which was contained in boxes. It was to be sent to England in a cruiser, and at the Cape Town railway station he had handed over the boxes to a naval guard and obtained from the lieutenant a receipt for a definite number, which they had both counted, and checked.

(£100 in 1914 is equivalent in purchasing power to about £14,460.57 today, an increase of £14,360.57 over 110 years. The pound had an average inflation rate of 4.63% per year between 1914 and today, producing a cumulative price increase of 14,360.57%.

This means that today’s prices are 144.61 times as high as average prices since 1914, according to the Office for National Statistics composite price index. A pound today only buys 0.692% of what it could buy back then – https://www.in2013dollars.com/uk/inflation/1914 )

As we were dining together a telephone message was received from an agitated naval lieutenant to say that on recounting the gold, they found that one box was missing, Giles left for the railway station, and returned to report that the missing box had been found in the ladies’ waiting room; how it got there has remained a mystery to this day.

The British Government were so afraid that the enemy might hear of this shipment, and try to intercept it, that I heard it had been transhipped twice before it reached England”. (African Manhunts, 1936 page 62).

I quote this story to prove that the British did move bullion in time of war.

CLEMENT LESLIE CHANDLER (KNOWN AS LESLIE)

By Errol Chandler

Born: 4 June 1893, Pontybodkin, North Wales.

- Son of an Englishman and a Welsh mother.

- Father was in Wales to manage a coal mine owned by the family.

- The firm of Samuel Chandler & Sons had its HQ in London.

- They manufactured machinery used in the production of coal gas.

- The family moved from Wales to London in 1896.

- On 11 October 1897 Leslie was enrolled at Stockwell College, London, the school record shows that he was a pupil there for only 11 days.

- The family firm did a lot of business in Imperial Russia.

- His father, Josiah Clement Chandler, was appointed to run the branch in Russia.

The family were getting ready to leave when one of the children became ill. It was decided that Josiah would go, taking only the oldest child, Clement Leslie, then aged 4 years. The rest of the family never went to Russia. Leslie was educated there. He grew up with Russian children and adopted their lifestyle.

So far as is known, Leslie and his father returned on a visit to England in 1901. They are recorded as being in London for the census of that year.

When Leslie was 16 years old, he returned to England to join the Royal Navy. His fluency in Russian must have drawn attention and was the cause of his next move.

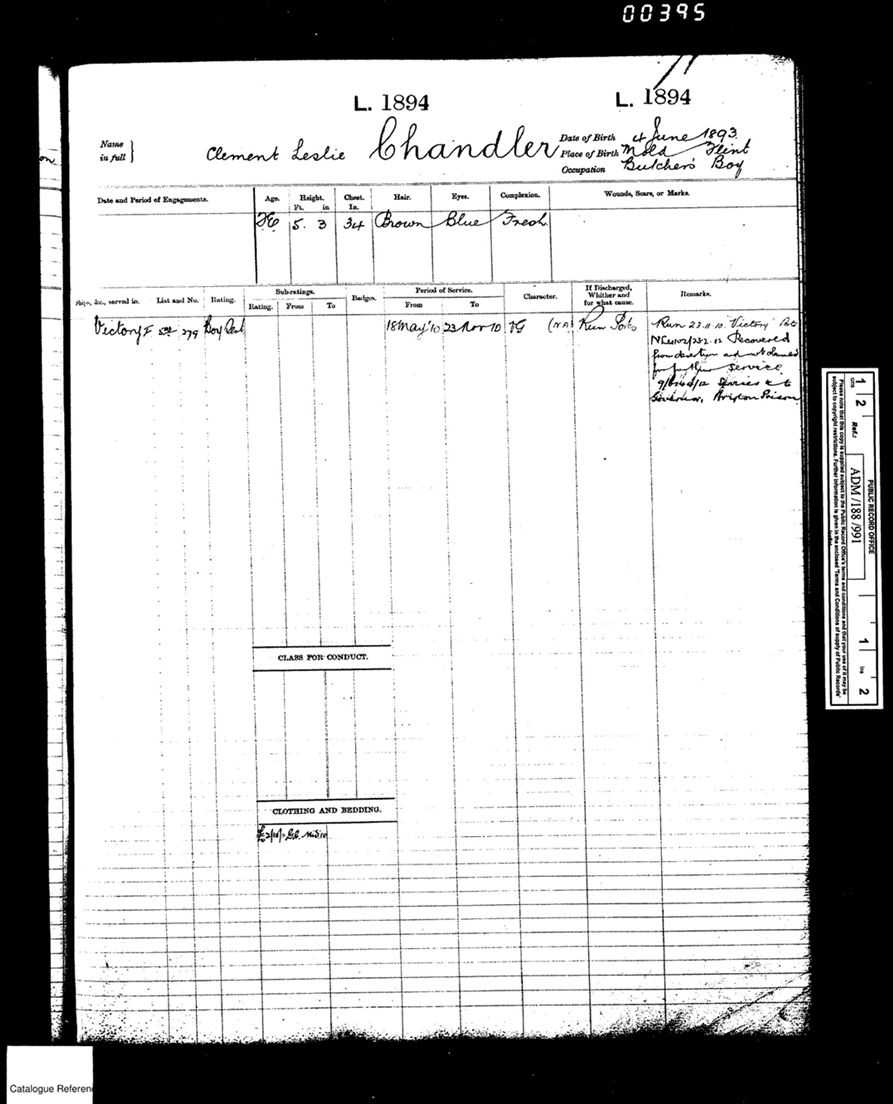

His Service Record shows that he joined on 18 May 1910 at RN Shore Establishment, HMS Victory, Portsmouth. The next entry says he went AWOL on 20 November 1910, 6 months after joining. Yet his Service Record gives his conduct as “G” (good).

There is a strange entry on his service record. His occupation when joining is given as “Butcher’s Boy.” Such an occupation would describe a young boy who cleaned the shop and delivered to customers. Leslie was from a wealthy family. It is inconceivable that he would have been a “butcher’s boy.” On 23 November 1910, an entry states “not fit for further service.” In other words, discharged. Interestingly, it does not say “dishonourably discharged.”

Then follows a couple of indecipherable words and “Governor Brixton Prison.” One must conclude that he was moved to the prison.

The next record of him is the 1911 Census in England conducted on the night of April 3rd. He is recorded as being at home with his parents and siblings at 51 Oakbank Grove, Herne Hill, London. However, against Leslie an entry (which is crossed out) reads “At Sea.”

He is also recorded at a Seamen’s Hostel in Southampton. He is described as a 17-year-old “ships servant”, born in Wales.

This was 6 months after he went AWOL and tells us that he had joined the Merchant Navy.

In the Calendar of Prisoners appearing before the court at Sessions House, Newington, London on Tuesday 2nd April 1912 is a Leslie Chandler, aged 18, a valet accused of stealing an overcoat and other items from his employer, Mr. Myer Rubinstein. He had been taken into custody on 11th March 1912. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 2 years in a Borstal institution.

The charge sheet records a previous conviction at Winchester Petty Sessions on 16th October 1911, under the name of Peter Henry (or Harry) Jones. Jones was the maiden name of his mother. That was for stealing a watch and a purse (two charges.) The sentence recorded: 3 months and I month. Borstal Records have not been found. (Neither has any Brixton Prison record been found, despite the mention on his RN Service Record)

It is difficult to square the charges and subsequent detention for two years (meaning a release approx. 2nd April 1914) with his known movements immediately following that date.

On 20th July 1914 he signed on as a crew member (a steward) on the ship S.S. St. Ronald. The voyage terminated at Liverpool on 3rd December 1914… after about 3,5 months duration. The Crew List (agreement) is stamped by port authorities in Liverpool, Antwerp, Montevideo, Buenos Aires and Rosario (Argentina).

As no prison or Borstal records that include Leslie can be found the assumption is made that the AWOL, theft accusations and subsequent convictions were fabricated to cover his disappearance from the Royal Navy on being recruited by the Secret Service.

His time as a seaman was part of his training, and to create a background. He signed again to the St. Ronald in 1915. No details of the voyage exist, other than a list of crew members. It was war time.

The crew-list of the S.S. St Ronald records that she commenced a voyage from New York, USA on 16 October 1915, scheduled to terminate on 21 November 1916 at Bordeaux, France. Among the crew is Leslie Chandler, aged 22, born in Pontybodkin and giving his home address as Pound Street, Carshalton, Surrey (England). The list is stamped by British Consuls in New York; Nagasaki, Japan; Adelaide, South Australia; Lisbon; Baltimore; Iquique, Chile and Vladivostok, Russia which it reached on 13th January 1916.

On the crew list, against his name and dated 11 February 1916, is written, “Deserted Vladivostok”.

During a conversation with his third son, Norman, he mentioned being involved in “the delivery of gold from Russia.” It was a casual comment, he gave no details.

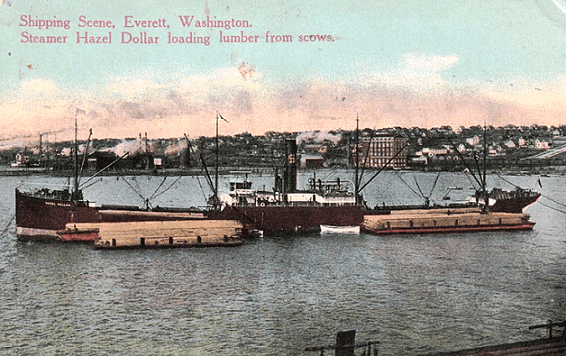

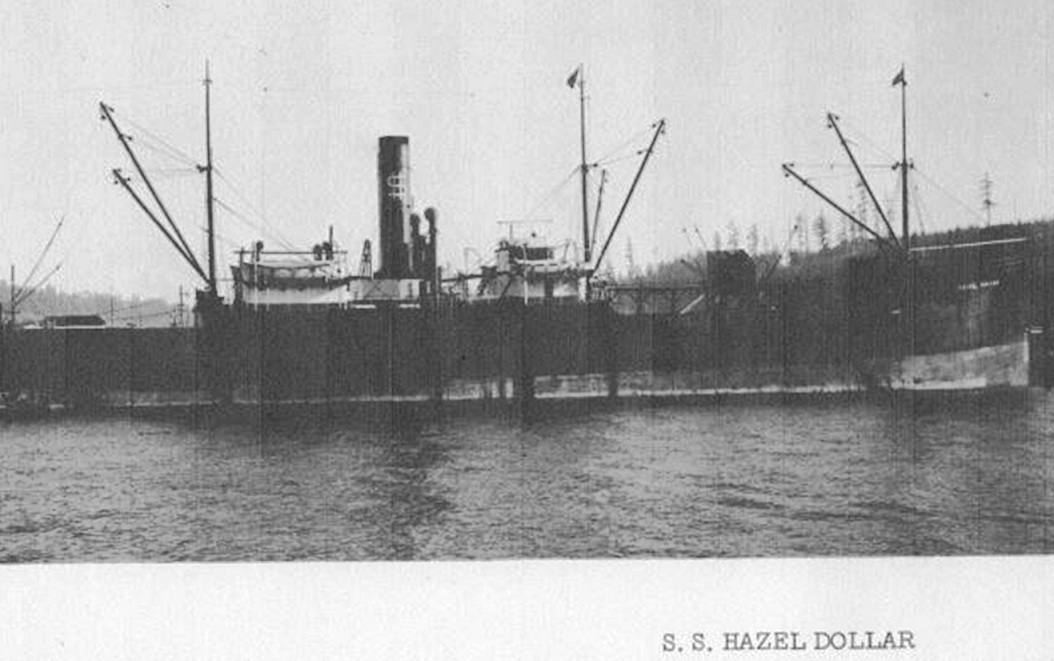

What happened in the four weeks between the ship arriving on 11 February and his desertion a month later cannot be explained. However, it was at this time that a ship called the S.S. Hazel Dollar entered the picture. Owned by the Dollar Shipping line of America but under the British flag, she had been chartered by the British and French governments to transport military equipment and supplies (which they financed) from Seattle, USA to Vladivostok. This was a key element of the French and British decision to supply the Imperial Russian Army with supplies, to keep them fighting Germany on the German East Front. By tying up half the German forces in the East, the British and French could just hold back the Germans on the Western front. If Russia collapsed in the East, Germany could switch a million more men to the West and overpower France and Britain.

The deal was that Russia would pay for the supplies in solid gold. The ship arriving with the supplies would receive the gold and sail to Vancouver, Canada to deposit it with the gold reserves of France and Britain which had been deposited there in case of a German win in WW1. After Vancouver, the ship would sail again for Seattle to start another triangular “arms for gold” voyage. In 1915, 1916 and 1917 the Hazel Dollar completed four such voyages.

Crossing the Pacific unescorted, she was a prime target for the German Navy. Aware of what she was carrying, the German High Command issued explicit orders to their agents in (neutral) America: “Sink the Hazel Dollar.”

She was never detected at sea, so the German agents in the US were ordered to start a sabotage campaign against the arms-producing factories and the railroads transporting the equipment to Seattle. They succeeded in destroying one shipment on the dockside, but the Hazel Dollar was unharmed.

Leslie was familiar with the Hazel Dollar. When he first joined the St. Ronald in 1914, he named his previous ship as having been the Hazel Dollar.

Between deserting in Vladivostok on 11 February and joining the Hazel Dollar to escort the gold on a 1916 voyage to Vancouver he would have reported to the British Embassy in Petrograd, then the capital of Imperial Russia.

It was, until WW1, called St. Petersburg. After the revolution, the Communists renamed the city Leningrad. After the collapse of Communism, it reverted to its former name, St. Petersburg. By train from Vladivostok to Petrograd, over 9,700 kms (6,020 miles), would have taken 14 days or more. He would have received his orders and travelled back to Vladivostok. It fits the time frame of 28 days between arriving on the St. Ronald and being recorded as a deserter. Would the ship have remained in Vladivostok for that length of time while waiting for the gold? It is possible / probable that Leslie travelled to Petrograd for instructions and then returned to Vladivostok, reported back on the ship, and then deserted to join the Hazel Dollar as part of the escort for the safe delivery of the gold to Vancouver? There were two shipments in 1916… June and December.

I have a letter, naming Leslie, written in November 1917 by a nurse at a hospital in Petrograd. He had arrived in the city by train with another Englishman, John Gordon Dickson. They had travelled together (it is not clear where from). On the journey Mr. Dickson caught pneumonia. On arrival in Petrograd Leslie took him to the British Nursing home. He was cared for by the doctors there but died ten days later.

The nurse, Mary McElhone, wrote the letter to the parents of Dickson (living in Wakefield, Yorkshire, England) informing them that their son had died. She describes how he was cared for and how “the arrangements” were carried out by “his friend” Mr. Chandler. In the embassy documents, there is an entry about the death. It is signed by Leslie.

Further embassy documents detail that Leslie was instructed to return to England to personally inform the parents and to return to them the personal items their son had with him when he died. Another document confirms that he had carried out the instruction. The documents also inform the parents of the address at which Leslie lived in England. That address is confirmed, by census records, as being the address of Leslie’s parents.

On 14th December 1917, the Chicago Tribune newspaper in the USA carried a report in their first edition of that day. It was removed from all their next editions of that date. The report was based on official US government documents recording that the USA and the UK were jointly providing $150,000 to fund an intelligence operation. The operation has never been revealed however, it was widely rumoured at the time that the British and Americans were keen to rescue the Russian Czar and his family, and a deal was being made with the Bolsheviks that, in return for releasing the Romanov family, the US and the UK would formally recognise the Bolsheviks as the legitimate government of Russia. Germany brokered this. The German Kaiser, being a cousin of Czar Nicholas, wanted for personal and political reasons to ensure the safety of the Romanov family.

On 3rd March 1918, the Germans and the Bolsheviks signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk. It contains a guarantee from the Bolshevik government (of Lenin) that no harm would come to the Romanov family and their safe release would secure diplomatic recognition of the newly formed Russian state.

Records show that in July 1918 “A team of international agents” took the whole Romanov family from Ekaterinburg, where they were being held captive, to Odessa, and put them on board a US Navy ship that sailed to the US base on Malta. From there a British battleship, HMS Lord Nelson, took them to Trieste (Italy) from where they travelled to Vienna and finally to exile in Warsaw.

Based on the evidence that exists, it seems unlikely that the “murder” of the Czar and his entire family ever happened. It was “fake news” to gain diplomatic recognition for the new Russian State.

Some years ago, it was claimed that human bones found in a well near Ekaterinburg were those of the Romanov family. Using samples from Prince Philip of Britain (a relative of the Romanovs) DNA testing gave a positive match, and the world was told the matter was finally resolved … they had been murdered. However, DNA testing has vastly improved and is now far more accurate. Requests for a re-test have been refused by Russia. Historians believe that modern Russia does not want to resurrect the Czar and face the possible emergence of his descendants.

On 31 August 1918, the Cheka (Soviet Secret Police) raided the British Embassy in Petrograd. They claimed it was a “nest of spies.” They forced their way in and shot dead the acting ambassador, Francis Cromie. They then arrested everyone on the premises and took them to prison. Some escaped, including Leslie. Years later, his nephew in England wrote of his childhood memories, one was about his uncle Leslie who “as WW1 was ending was traveling in Russia and China”. He was, on the run escaping from the Cheka! He made his way back to the UK via China. The raid on the embassy and the murder of Francis Cromie caused a huge diplomatic incident. All leading nations got together and told the Russians that unless they released the prisoners all Russian embassies in the world would be closed, all Russian diplomats arrested and a world-wide trade boycott of Russia would begin, backed up by a naval blockade and declaration of war on Russia.

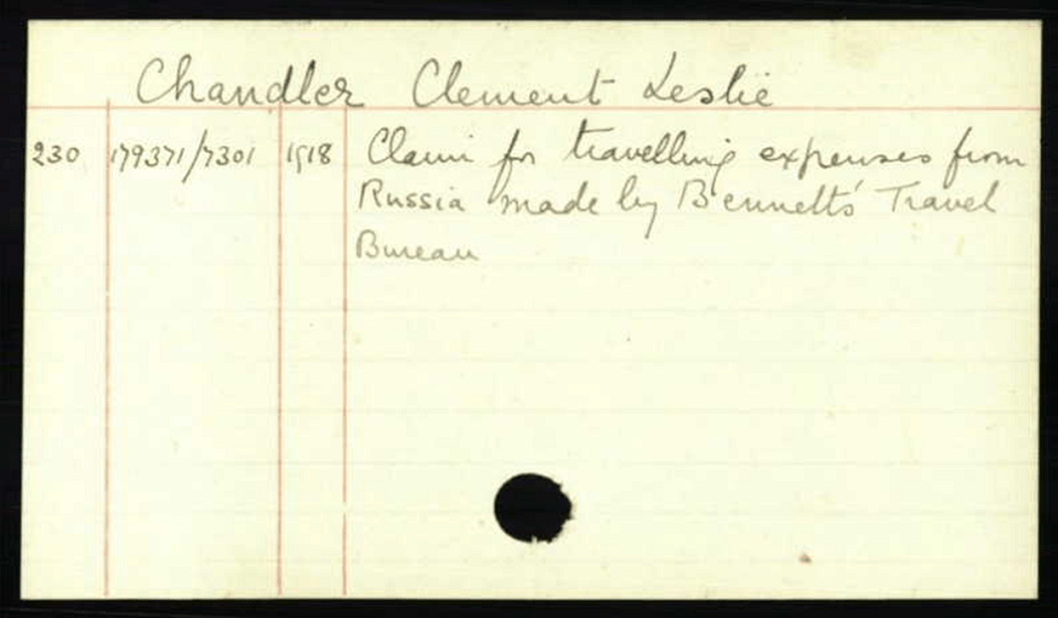

British Foreign Office records include 1918 expenses claim by Clement Leslie Chandler for “travelling expenses from Russia”. This may have been for his expenses while escaping.

Leslie told one of his sons about a mission he was on.

In August 1918 he was in a team of UK and US agents sent from San Francisco to Vladivostok to rescue diplomats trapped there by advancing Bolshevik forces. Due to naval activity off the port, it was decided that a safe return to San Francisco was not possible. They then took the rescued across Siberia, an epic journey of 11,500 km (7,100 miles) to Bergen, Norway which took two months in very dangerous circumstances. From there the Royal Navy took them to Aberdeen, Scotland.

In March 1919 he was part of a team inserted into Russia tasked with finding and rescuing members of the Russian aristocracy who were being persecuted by the Bolsheviks. These included Dowager Empress Marie, the mother of Czar Nicholas, his uncles (Grand Dukes), cousins, other relations, and Tsarist politicians. They had expected at most two-dozen people but were almost overwhelmed by the number of desperate people seeking to escape their homeland. The team of agents delivered them safely to Yalta, Crimea on the Black Sea. Once there, they boarded the battleship HMS Marlborough, which had arrived from Constantinople on 8th April. The arrival of so many people and tons of luggage created chaotic conditions. The officers of HMS Marlborough could not speak Russian and it fell to Leslie and a fellow agent to act as interpreters. The last of the evacuees boarded on the 11th and HMS Marlborough weighed anchor and sailed for Constantinople.

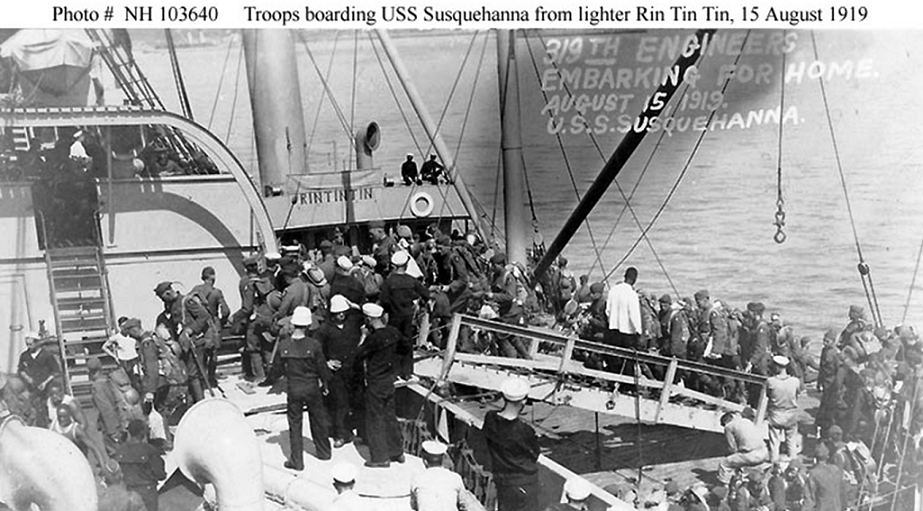

When WW1 ended there were more than one million American soldiers in France. With the war ended, all wanted to get back home as quickly as possible. Transport ships of every description were being used. One of the problems was the state of the harbours on the French coast. They were incapable of handling most of the ships, so a ferry service had to be organised, using small ships, lighters and tugs to take the men from the shore to the large ships lying at anchor.

One of the small ships was the United States Navy Rin-Tin-Tin. She had started life as collier of the Royal Navy, called Renfrew. Pressed into service as a ferry for the troops the Americans named her Rin-Tin-Tin, after the dog made famous in Hollywood movies. In US naval records there are photographs of the troop-ferrying operation.

Taken by returning soldiers, some have words written on them. One is of a ship called the Susquehanna. Written on it are the words “The ship that brought us home.” That ship had been the German Lloyd liner, Rhine. She was impounded in a US port when America entered the war, renamed Susquehanna and became part of the US Navy transport fleet.

While researching this project I had been asking my older brothers for any memories they may have of what Dad had told them. Independently one who was living in Durban called me and told me he remembered Dad talking about a ship called Susquehanna. Nothing else, just the name. Almost in the same week another brother, then living in Botswana, was telling me what he remembered, and said that Dad had spoken about a ship called Rin-Tin-Tin.

There was no connection until I was studying the photographs in the US Navy archives. In one of them is a large ship with a small one tied alongside. Men are climbing up nets to board the bigger one. She is the Susquehanna.

Across the bridge of the smaller one is the name Rin-Tin-Tin.

I can only imagine that at some point of the repatriation Dad was involved, probably checking to see if any enemy were infiltrating among the soldiers.

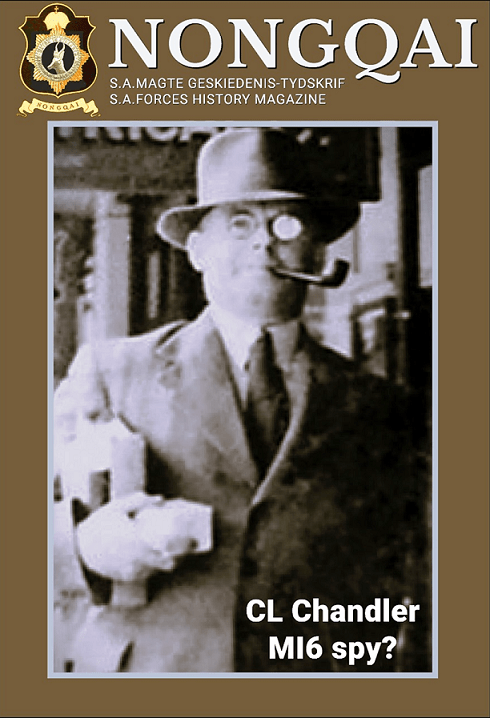

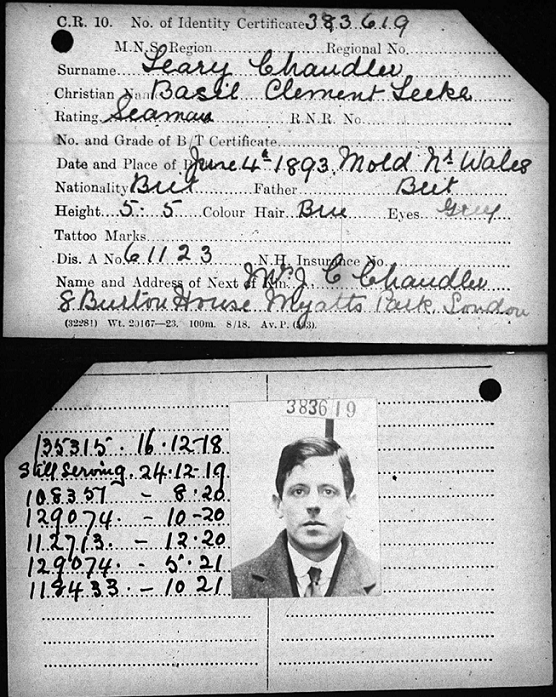

The next record of Dad is a Seaman’s Identity Card. This was found in the National Archives, Kew, London, England.

Issued in December 1918, it lists six ships he was crew on between 1918 and 1921. It is fake. It features his photograph, his physical description, and his parents as next of kin at their London address (as it appears in the census). However, the Christian names he is given are:

Basil Clement Leeke. And the surname is Leary Chandler.

Only two of those have any truth in them. Clement and Leslie.

As this is an official document found in the National Archives, it must have been officially sanctioned. I have found other crew lists that show he was at sea until about 1932, but I have not found another identity card.

Most of the ships were of the Union Castle Line on the regular mail run between Southampton and South Africa. On the contracts (crew lists) that are signed by the men, he signs as L. Chandler or B.L Chandler.

On 19 July 1922, he became a member of the St. Finbar’s Masonic Lodge at Rossburgh, Durban. The lodge records show that he ceased to be a member on 30 June 1930.

I believe it must have been part of a cover he used on his Union Castle postings. I wonder if he was receiving Instructions or giving instructions?

Every time, his job on a ship would bring him into contact with passengers and crew. For example: Dining Room Steward, Bar Steward, Baggage Attendant, Cabin Steward, and so on. In such roles, he could be near all, while just seen as part of the “furniture.” You could say he was “Hiding in plain sight.” He could overhear conversations and have access to cabins and baggage. The friendly guy who was just there to help!

After he left the sea, we lived in Port Elizabeth. The Union Castle ships used to meet there at the weekend, one from the UK, the other bound for the UK. Without fail, he would visit them. I and my sister (we were aged 7 and 5) would go with him. When the ships were closed to the public he would walk to the gangway and flash a badge at the guard and was immediately waved on board. We children were left in the ship’s bakery and Dad would disappear for an hour while the bakers fed us cakes and orange juice. We had no idea what he was doing. I now realise he must have been giving or passing information to a colleague on board.

Whatever Dad was doing, he never spoke about it.

There were occasional snippets, more throw-away comments to his teenage sons. My mother had no idea he spoke Russian. One day she wanted to sell an item of furniture and called the local second-hand furniture dealer, an elderly Russian-Jewish man. He came to the house, and she showed him the item for sale, he offered her a price which she accepted. She then offered him a cup of tea. While she was in the kitchen preparing it Dad came home and found the man alone in the lounge. The guy told Dad he was buying the bit of furniture and would arrange for it to be collected. Dad asked him how much he was paying. On being told Dad, knowing the true value, exploded with anger and in fluent Russian told the dealer his fortune and ordered him out of the house. My mother, hearing raised voices using words she could not understand, hurried into the lounge thinking a fight was taking place.

The furniture guy, so shocked to be told in pure Russian what to do with himself, immediately apologised and offered to treble his original offer.

Dad had what I believe is or was a Russian habit. He liked to drink his tea out of a tall glass, no milk, lots of sugar and a slice of lemon.

He was a lifelong teetotaller.

He smoked a pipe.

My oldest brother Chester (he is now 88) recalls Dad doing the Cossack Dance at parties, very energetic, squatting down and kicking the feet forward alternately. He would have learned the dance when a schoolboy in Russia.

He was 5 feet 5 inches tall. All his sons are over 6 feet.

I and my four brothers grew up never dreaming that our seemingly mild and unadventurous father had lived such an eventful life.

Even in death, there is a mystery!

His birth certificate gives his date of birth as 4 June 1893. His gravestone at Forest Hills Cemetery, Port Elizabeth has it as 4 June 1895. He died in Summerstrand, Port Elizabeth on Saturday, 30 November 1957.

When Dad was buried there in 1957, I was 13. It was a desolate, windswept place. The sand was blowing and stinging my bare legs.At the time we thought of having the date corrected, but decided to leave it as it is.

In light of what we have since discovered, it is yet another mystery surrounding Dad. I am hoping that someone, somewhere reads this and will recall something they experienced or heard, that will yield more information.

Dad was a mystery in life and death!

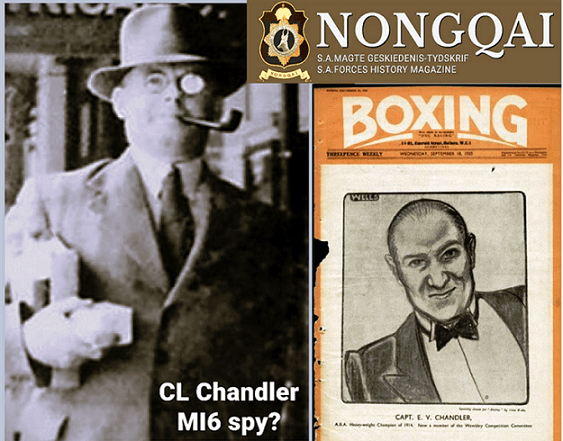

Photos

1. Comments

I am currently writing a book about him. It is largely based on the facts in this summary but will have a certain amount of fiction woven in to create a storyline. It has attracted the attention of some literary agents; I am hopeful that it will be accepted for publication this year.

I am happy for you to use in your magazine what I have told you, on the understanding that it is my copyright.

Thank you.

Errol Chandler

Somerset, England. January 2024

2. Comments

I have attached photos of the SS Hazel Dollar. A real old tub!

She carried the arms for gold across the Pacific from Seattle to Vladivostok and brought the gold back to Vancouver. She did four such triangular missions. A real old tub!

Looking at it I would not have been happy sitting on tons of high explosives and arms, unescorted, knowing the German navy was intent on sinking it somewhere in the Pacific Ocean.

If they had succeeded Dad would not have survived and I would not exist!

One of my brothers told me that Dad received some sort of award from the King. (George V). I am not sure about it and am told that awards to MI5 & MI6 people are not made public.

Errol.

3. Comments

Attached is what I have prepared for you. I would like to know what you make of it. Once you have read it you may have some questions. I will answer as best I can.

I have had some very good help. Once they got the flavour of his life-story people gave me their professional help and advice…. all free of charge!

History professors, university librarians, an ex-MI5 man, professional genealogists, archives in the UK, USA and Canada.

It was quite overwhelming and had made everything possible.

Regards

Errol

4. Comments

Dear Hennie,

You wrote about a box of gold going missing.

That jogged the memory! Dad told two of my brothers about his dealings with what was known as the Czech Legion. As I understand it, a semi-mercenary force, some 10,000 strong, that fought for the Czar during the Russian Civil War/revolution. Apparently, as the Bolsheviks were taking over Russia, the Legion was not getting paid. So, they took (stole) an entire train-wagon load of gold that was going from Petrograd to Vladivostok.

It might have been the final such cargo for the Hazel Dollar. It is alleged, that the gold formed the capital for a bank they set up in their homeland.

Chester (oldest brother), confirmed with me today that Dad spoke to him of traveling by train in Russia with a diplomatic pouch chained to his wrist and using the revolver he was issued with.

He also tells me that Dad used to mention the “Silver Greyhounds”. That goes back to the diplomatic couriers for King Charles II. The silver greyhounds were broken off a silver ornament that the king had.

(Comments by HBH: Was I was stationed at the old Louis Botha Airport in Durban during 1969 I regularly saw the Queens Messenger arriving with an attaché case chained to his wrist.)

He was in exile in Holland after his father was beheaded by Cromwell. He gave them to his trusted associates so that when they met, the piece of silver was like an identity card which only the most trusted emissaries had. These days they are called Kings Messengers.

For confirmation about the Hazel Dollar, a good reference is the book, “The Enemy Within” – “The Inside Story of German Espionage in America”, written by Captain Henry Landau, published in 1937.

…

This might interest you.

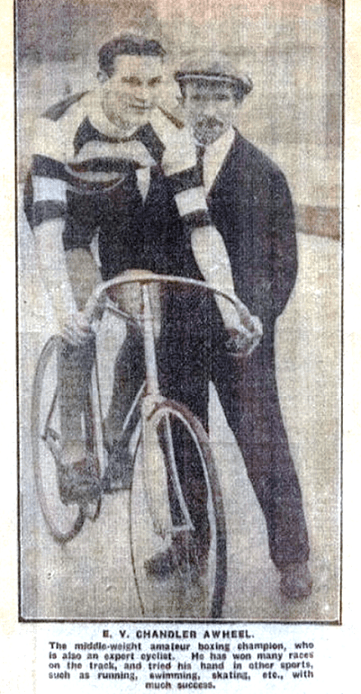

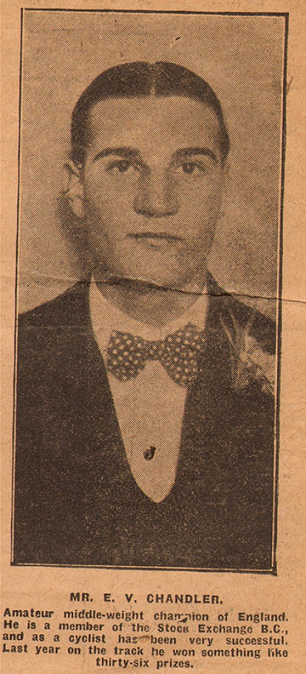

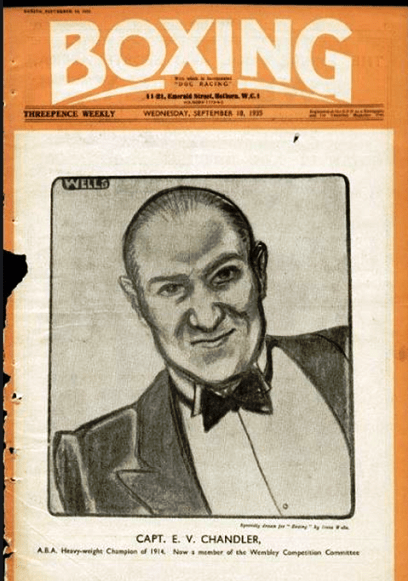

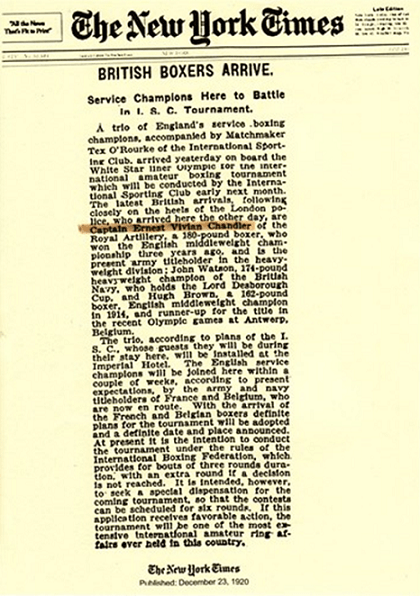

Leslie had a cousin, Ernest Vivian Chandler, born in London on 31 July 1891. I have no concrete proof, but I think he was an early recruit of Cumming and used his sporting connections for spying.

He certainly had access to the movers and shakers of the time and was very well connected if he was a spy.

He was a “gentleman sportsman”. In other words, he was self-funded (or funded by his family.) Gentleman sportsmen were very respected and came from or moved in the top social circles.

At an early age, he showed promise as a boxer and began winning bouts on the amateur circuit in the UK. In 1914 he became the British Amateur middle-weight champion.

During WW1 he was in the British army and toured the training camps giving boxing displays to the troops and advising on their fitness programmes.

After the war he toured America as a member of the British Forces boxing team, they won every division!

He took part in exhibition boxing tournaments, raising money for charity….both in the UK and in the USA. In those tournaments, he boxed with world-famous professionals, such as Primo Canera and Jack Dempsey, among

others.

An indication of the social circles he moved in…. he was invited by a German prince to inspect the stadium and facilities for the Berlin Olympics in 1936.

(Comments by HBH – A South African Sydney Robey Leibbrandt also took part in the 1936 Olympics as a boxer. He later became a paratrooper in the German forces and came back to South Africa on a secret mission. This is a story on its own.)

He became a stockbroker in London and was a member of the Stock Exchange Boxing Club.

He was also a very successful racing cyclist, winning at many events.

He was a good golfer and was secretary of the Pyecombe Golf Club, near Brighton, UK.

His earliest trophy is played for in a golf tournament at Pyecombe in September every year, “The Ernest Chandler Memorial Cup.” It has the original boxing inscription and the golf club inscription.

I went to the club to see the trophy.

He died in 1936 after contracting blood poisoning. He had volunteered to give blood to save the life of a very good friend, Sir Harry Preston, hotelier, and sports promoter.

The incision in his arm became infected and he died three days later.

His brother, (Samuel Briscoe Chandler) on hearing the news had a heart attack and died. To compound the tragedy, the friend (Sir Harry Preston) he had donated blood for also died in the same week.

Ernest and his brother are buried in the Chandler family vault at Nunhead Cemetery, London.

I have attached some photos of Ernest and his life.

I will send you a couple more photos of Dad. I have no more documents about him…. but things seem to surface as time goes on, so I am hoping for more!

If possible, I would like copies for myself, my two surviving brothers, and my two daughters, please.

Regards

Errol. (29 Jan 2024)

Photographs sent by Errol

Annexure “A”

Dad: Summary of sightings, other than the crew lists. 26/1/1921

20/7/1914 signed on to Saint Ronald in North Shields.

31/12/1914 signed off the Saint Ronald in Liverpool.

Then nothing, until he re-joins the Saint Ronald in New York.

16/10/1915 Signed on with the Saint Ronald in New York for a voyage scheduled to last 13 months.

11/2/1916 deserts in Vladivostok, 4 months into the voyage.

November 1917. Arrives in St. Petersburg by train from Vladivostok. Later that month Nursing Sister M. McElhone. at the British Nursing Home, Petrograd wrote to the Dickson’s expressing her sympathies and telling of their son’s 10 days in the hospital. She mentions that “his friend Mr Chandler” was with him and attended to the arrangements.

**15 May 1918 he is named in correspondence between the Embassy in St. Petersburg and the Foreign Office, London which states he is returning to England to give the parents the personal effects of their deceased son John Gordon Dickson, (JGD.), his companion on the train.

**18 May 1918 again named in correspondence to Foreign Office. He is referred to as an Embassy clerk. (A euphemism for “spook”?)

**22 May 1918 once again is named (three times) in connection with JGD’ effects, his English address is given as 8 Burton House, Myatt’s Park.

1/6/1918 A letter from Dr. Dickson (father of JGD) to the Foreign Office stating that he had received a telegram from Mr. Chandler in late November 1917 conveying the news of the death of JGD. The letter confirms that Mr Chandler had visited him in Huddersfield and returned his sons effects and gave details about the death. The Foreign Office wanted the funeral costs to be paid. No further sightings until an undated record at the Foreign Office, London records his claim for travel expenses in Russia at some point in 1918.

31/8/1918 British Embassy raided by Bolshevik police. All on the premises arrested as spies. A few got away. I think the nephew’s diary about Uncle Leslie “Journeying in Russia and Chinas as WW1 was ending” meant he was making his escape back to England. The fake ID card starts on 16/12/1918.

**Hard to be precise with dates. In Russia they used both the Julian & Gregorian calendars.

Annexure “B”

Some history on MI6 1909 – 1924 as per wikipedia:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (February 2024)

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 (Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligence on foreign nationals in support of its Five Eyes partners. SIS is one of the British intelligence agencies and the Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service (“C”) is directly accountable to the Foreign Secretary.[3]

Formed in 1909 as the foreign section of the Secret Service Bureau, the section grew greatly during the First World War officially adopting its current name around 1920.[4] The name “MI6” (meaning Military Intelligence, Section 6) originated as a convenient label during the Second World War, when SIS was known by many names. It is still commonly used today.[4] The existence of SIS was not officially acknowledged until 1994.[5] That year the Intelligence Services Act 1994 (ISA) was introduced to Parliament, to place the organisation on a statutory footing for the first time. It provides the legal basis for its operations. Today, SIS is subject to public oversight by the Investigatory Powers Tribunal and the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament.[6]

The stated priority roles of SIS are counter-terrorism, counter-proliferation, providing intelligence in support of cyber security, and supporting stability overseas to disrupt terrorism and other criminal activities.[7] Unlike its main sister agencies, Security Service (MI5) and Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), SIS works exclusively in foreign intelligence gathering; the ISA allows it to carry out operations only against persons outside the British Islands.[8] Some of SIS’s actions since the 2000s have attracted significant controversy, such as its alleged complicity in acts of enhanced interrogation techniques and extraordinary rendition.[9][10]

Since 1994, SIS headquarters have been in the SIS Building in London, on the South Bank of the River Thames.[11]

History and development

Foundation

The service derived from the Secret Service Bureau, which was founded on 1 October 1909.[4] The Bureau was a joint initiative of the Admiralty and the War Office to control secret intelligence operations in the UK and overseas, particularly concentrating on the activities of the Imperial German government. The bureau was split into naval and army sections which, over time, specialised in foreign espionage and internal counter-espionage activities, respectively. This specialisation was because the Admiralty wanted to know the maritime strength of the Imperial German Navy. This specialisation was formalised before 1914. During the First World War in 1916, the two sections underwent administrative changes so that the foreign section became the section MI1(c) of the Directorate of Military Intelligence.[12]

Its first director was Captain Sir Mansfield George Smith-Cumming, who often dropped the Smith in routine communication. He typically signed correspondence with his initial C in green ink. This usage evolved as a code name, and has been adhered to by all subsequent directors of SIS when signing documents to retain anonymity.[4][13][14]

First World War

The service’s performance during the First World War was mixed, because it was unable to establish a network in Germany itself. Most of its results came from military and commercial intelligence collected through networks in neutral countries, occupied territories, and Russia.[15] During the war, MI6 had its main European office in Rotterdam from where it coordinated espionage in Germany and occupied Belgium.[16] A crucial element in the war effort from the British perspective was the involvement of Russia, which kept millions of German soldiers that would otherwise be deployed on the Western Front, engaged on the Eastern Front. On 7 November 1917 the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin overthrow the Provisional government in Petrograd and signed an armistice with Germany.[17] From the British viewpoint that the Russia stay in the war, and MI6’s two chosen instruments for doing so were Sidney Reilly, who despite his Irish name was a Russian-Jewish adventurer, and George Alexander Hill, a British pilot and businessman.[18] Officially, Reilly’s mandate was to collect intelligence about the new regime in Russia and find a way to keep Russia in the war, but Reilly soon became involved in a plot to overthrow the Bolsheviks.[19]

Inter-war period

After the war, resources were significantly reduced but during the 1920s, SIS established a close operational relationship with the diplomatic service. In August 1919, Cumming created the new passport control department, providing diplomatic cover for agents abroad. The post of Passport Control Officer provided operatives with diplomatic immunity.[20] Circulating Sections established intelligence requirements and passed the intelligence back to its consumer departments, mainly the War Office and Admiralty.[21] Recruitment and the training of spies in the interwar period was quite casual.[22] Cumming referred to espionage as a “capital sport”, and expected his agents to learn the “tradecraft” of espionage while on their missions instead of before being dispatched on their missions.[22] One MI6 agent Leslie Nicholson recalled about his first assignment in Prague: “nobody gave me any tips on how to be a spy, how to make contact with, and worm vital information out of unsuspecting experts”.[22] It was not until the Second World War that the “methodical training” of agents that has been the hallmark of British intelligence started.[22] A number of MI6 agents like MI5 agents were former colonial police officers while MI6 displayed a strong bias against recruiting men with university degrees as universities were considered within MI6 to be bastions of “effete intellectualism”..[22] Claude Dansey, who served as the MI6 Deputy Chief in World War Two wrote: “I would never willing employ an university man. I have less fear of Bolshies and Fascists than I have of some pedantic, but vocal university professor”.[22]

The debate over the future structure of British Intelligence continued at length after the end of hostilities but Cumming managed to engineer the return of the Service to Foreign Office control. At this time, the organisation was known in Whitehall by a variety of titles including the Foreign Intelligence Service, the Secret Service, MI1(c), the Special Intelligence Service and even C’s organisation. Around 1920, it began increasingly to be referred to as the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), a title that it has continued to use to the present day, and which was enshrined in statute in the Intelligence Services Act 1994. During the Second World War, the name MI6 was used as a flag of convenience, the name by which it is frequently known in popular culture since.[4]

In the immediate post-war years under Sir Mansfield George Smith-Cumming and throughout most of the 1920s, SIS was focused on Communism, in particular, Russian Bolshevism. Examples include a thwarted operation to overthrow the Bolshevik government[23] in 1918 by SIS agents Sidney George Reilly[24] and Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart,[25] as well as more orthodox espionage efforts within early Soviet Russia headed by Captain George Hill.[26]

Smith-Cumming died suddenly at his home on 14 June 1923, shortly before he was due to retire, and was replaced as C by Admiral Sir Hugh “Quex” Sinclair. Sinclair created the following sections:

A central foreign counter-espionage Circulating Section, Section V, to liaise with the Security Service to collate counter-espionage reports from overseas stations.

An economic intelligence section, Section VII, to deal with trade, industry and contraband.

A clandestine radio communications organisation, Section VIII, to communicate with operatives and agents overseas.

Section N to exploit the contents of foreign diplomatic bags.

* Section D to conduct political covert actions and paramilitary operations in time of war. Section D would organise the Home Defence Scheme resistance organisation in the UK and come to be the foundation of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War.[20][27]

In 1924, MI6 intervened in the general election of that year by leaking the so-called Zinoviev letter to the Daily Mail, which published it on its front page on 25 October 1924.[28] The letter-which was a forgery-was supposedly from Grigory Zinoviev, the chief of the Comintern, ordering British Communists to take over the Labour Party. The Zinoviv letter, which was written in English, came into possession of the MI6 resident at the British Embassy in Riga on 9 October 1924 who forwarded it to London.[29] The Zinoviev letter played a key role in the defeat of the minority Labour government of Ramsay MacDonald and the victory of the Conservatives under Stanley Baldwin in the general election of 29 October 1924.[28] It has been established the MI6 leaked the Zinoviev letter to the Daily Mail, but it remains unclear if MI6 was aware that the letter was a forgery at the time.[30]