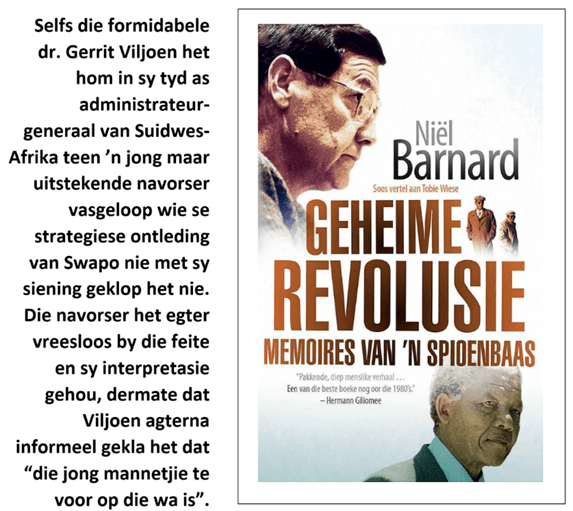

ABSTRACT: Nongqai series The Men Speak Dr Willem Steenkamp Part 2 – my years in Intelligence. Willem is the son of former SAP-SB CO Maj-Gen Frans Steenkamp. He is himself a former NIS officer who did his doctoral thesis on the intelligence function. He is also a novelist, ambassador, attorney, entrepreneur and polyglot with wide experience of living abroad. Currently, Willem volunteers as the co-editor and business manager of Nongqai magazine.

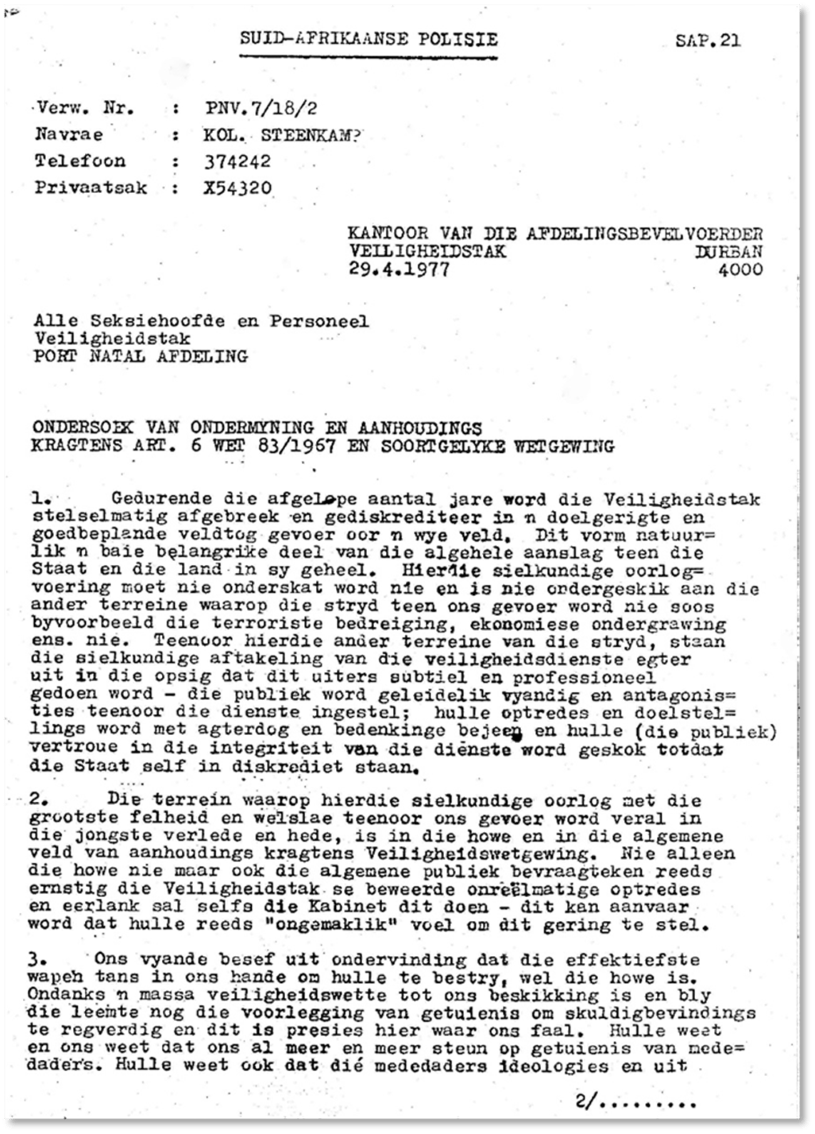

In this, Part 2, he shares his experiences and insights into South Africa’s transition, as acquired during his years in the National Intelligence Service. He gives his personal view on why and how the political war was lost, despite the “armed struggle” battles having been won. This is due to the fact that South Africa’s internal conflict had always been a political rather than a military contest. The ANC’s “armed struggle” was just one part of their propaganda war.

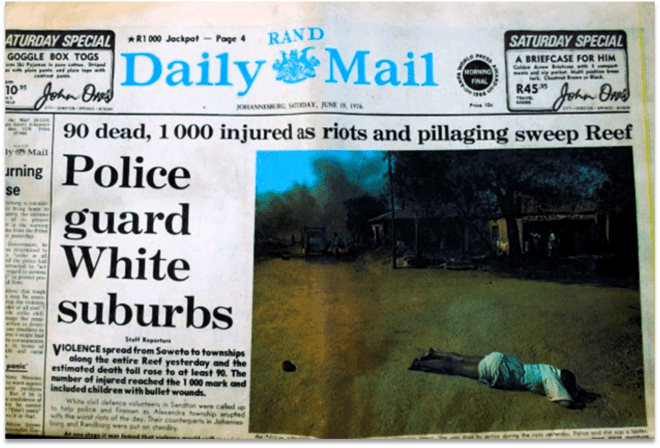

For the “lost decade” under PW Botha, the South African government had opted for a strategy of “shoot” rather than “settle”. This erroneous prioritisation caused them to decisively lose the propaganda war and thereby the contest for political power. The security forces may have won the battles, yet still, the war was lost. Because of poor strategic and policy choices that favoured short-term tactical gains, but entailed long-term strategic setbacks.

FOCUS KEYWORD: NONGQAI SERIES THE MEN SPEAK DR WILLEM STEENKAMP PART 2

KEYWORDS: South Africa, Apartheid, SACP/ANC, “armed struggle”, Genl Jan Smuts, Dr HF Verwoerd, Adv John Vorster, Mr PW Botha, Pres FW de Klerk, Pres Nelson Mandela, Min Pik Botha, Genl HJ (Lang Hendrik) van den Bergh, Dr Eschel Rhoodie, Dr LD (Niël) Barnard, Israel, USSR, BfSS/NIS, SAP-SB, SADF

AUTHOR: Dr Willem Steenkamp

(TO READ PART ONE, CLICK HERE)

PART TWO of: TACTICAL EXCELLENCE & GRIT WON US THE BATTLES, BUT POOR STRATEGY LOST US THE (POLITICAL) WAR

OBSERVING CRITICAL TIMES CLOSE-UP: MY YEARS IN INTELLIGENCE

1. THE NATURE AND STRUCTURE OF PART TWO

As promised in Part 1, in this second instalment of my fireside chat I will be focusing on the period in South Africa’s history from mid-1975 to the present. In this part I will be sharing my personal observations of key moments that constituted “forks in the road” for our people, during my time in intelligence. This period coincides with my own coming of age as young adult, allowing me to observe developments from close up, thanks to different positions fate had placed me in. Not as a decision-maker, but as a trained intelligence analyst, lawyer and political scientist, who happened to have had good vantage points from which to observe.

As in Part 1, my story will be interspersed with what I have learnt from my research (academic as well as latterly in my position as co-editor of Nongqai). I also had the benefit of people who had witnessed important events, having shared it with me.

I will attempt to not bore you with too much detail about my own experiences (as I’ve said, this isn’t really about me – it’s about the unfolding of “Our Story”, the historical path trodden by the South African nation and the Afrikaners in particular, which has brought us to where we are now).

However, I do understand that many of you will be interested in me recounting at least some of those experiences, where such personal accounts may help illuminate what it was like to have been in the security services, and more especially, in intelligence. I will try to oblige, always with the overriding aim, though, to try and answer that core question: how did we get from where we were, to where we are now?

To start out, however, I will tell you a little bit about my ancestry and youth, because I believe that people are formed by the times they live in, by their education and experiences, but also very much by their family background (the genes and the culturalization passed on to them), which in many ways determines their attitudes, talents and their circumstances.

So, without further ado, let me start telling you about the Steenkamps, and – from my mother’s side – the (Boere) O’Reilly’s that I’m proud to have as my forebears.

2. MY ANCESTRY AND YOUTH

2.1 The Steenkamps of Southern Africa:

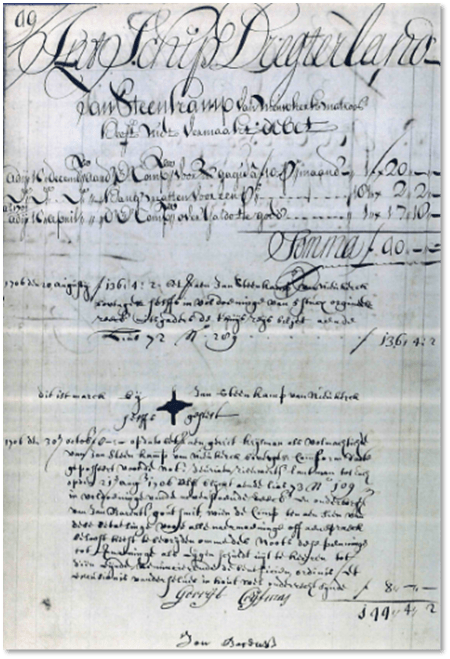

The first Steenkamp to set foot at the Old Cape did so at the end of the 1600s. Jan Harm Steenkamp was a young sailor/soldier from what is now the border area between modern-day Germany and the Netherlands He was employed by the VOC, the Dutch East-India Company.

Jan Harm had made a number of voyages to the Orient, passing by the Cape. One such was on the good ship “Dregterland”. Below is his pay slip, which he had signed with an X because of being illiterate at that time.

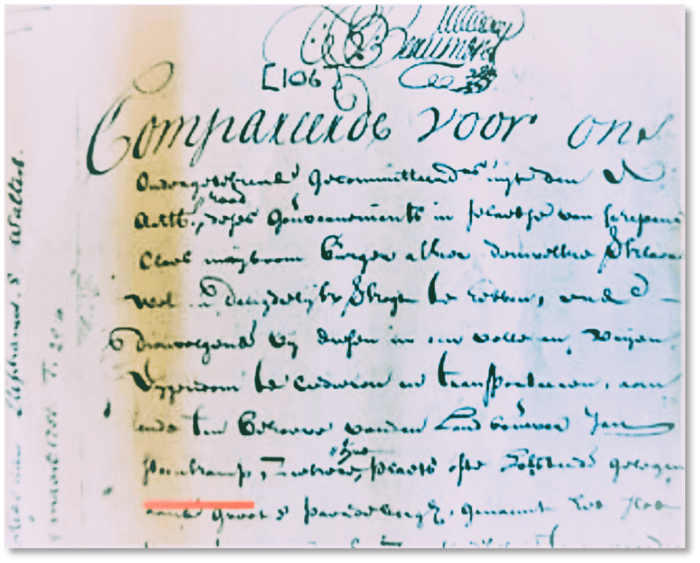

Jan Harm eventually decided to bid the oceans farewell and to settle at the Cape, where in October 1714 he married Geesje Visser, the daughter of a local Vryburger, and acquired the farm “Het Slot” in the Agter-Paarl. Below is a copy of Jan Harm’s original Title Deed to that farm, as still held by the Deeds Office in Cape Town (I had it researched by one of my law clerks, when I myself practised as attorney in Franschhoek):

Unfortunately, Geesje (Gesina) passed away just some four years after their marriage. Jan Harm then married Jannetjie van Eck, with whom he had ten kids – she thus became the “stam-moeder” of the Steenkamp clan of Southern Africa.

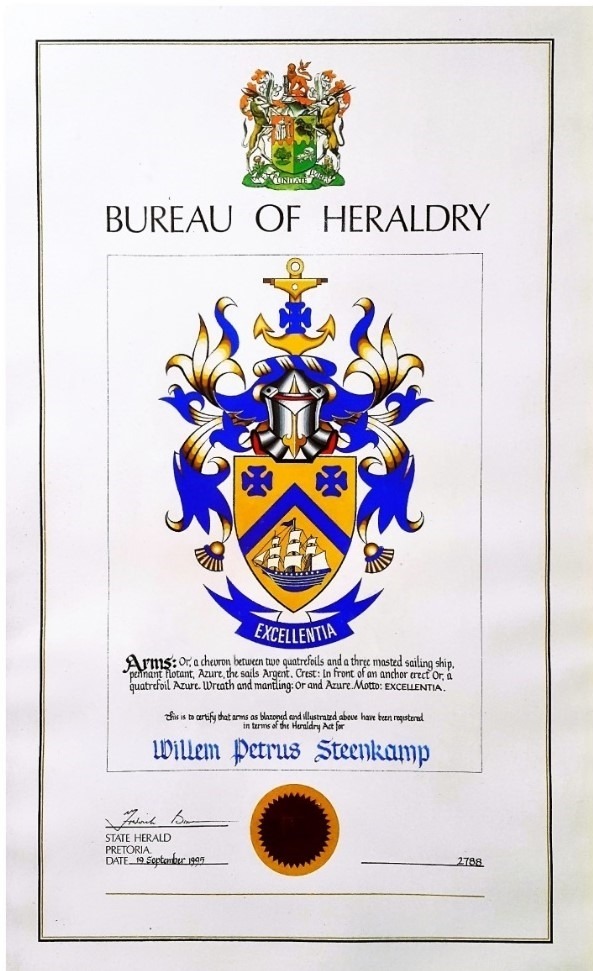

Jan Harm died in 1744. His signet ring (used to seal official documents by pressing it into a hot wax seal) today forms part of the Bell-Krynauw Collection in Cape Town. The central element of his seal was a three-masted ship, typical of the era. I incorporated it as main element of my own coat-of-arms, as designed by and registered with the Bureau of Heraldry (see below).

Our clan spread North-West from the Cape, into the Karroo and eventually Namaqualand.

Nowadays it is something to be proud of, to see your surname carved into the rocks on Robben Island. You may be surprised to learn that “Steenkamp” was one of the first to be carved there, by a lonely convict. He was one of my distant forebears, Jan “Slaai” Steenkamp. (I’ll recount the story here for its interest value, but essentially to show the obstreperous Steenkamp character traits that have carried through to later generations, such as my great-uncle Oudok (as related in Part One), my father and – I must admit – to myself as well).

It happened not long after the 2nd British occupation of the Cape, in the early 1800s. Jan Slaai farmed in the North-West. As often happened during those days, a roaming band of Bushmen decided to appropriate some of his livestock. In keeping with the law (as he had known it before the British), Jan Slaai immediately set off to the local Veldkornet (who had retained his positions under the Brits). Jan Slaai asked permission to send a small commando (similar to the American Wild West “posse”) after the Bushmen, which was approved. Doing so was urgent, because the Bushmen (who were hunter-gatherers, not pastoralists) obviously weren’t stealing the livestock to keep and raise, but to eat.

Permission given, Jan Slaai then tasked some of his local farmhands (who were good trackers and shots) to try and recover the livestock. They duly tracked down the Bushmen, encountering them at night around a barbeque fire. The little Khoi commando knew that it would be a seriously risky business to go argue the finer points of the law with the Bushmen in the dark and getting into a scrap with those doughty fighters with their poison arrows. Discretion thus got the better of their valour and they decided to shoot first and ask questions later.

Long story short, they returned with the ears of the Bushmen (as was the practice then) plus what remained of the livestock as proof of mission accomplished. Frontier justice, as it was then applied.

Nothing would likely have come of the matter, had Jan Slaai and his foreman who had led the little expedition not gotten embroiled in a heated dispute about a totally different matter soon afterwards. The foreman fled the farm and lodged a complaint against his former employer with the new British authorities. During their investigation the whole matter of the dead band of Bushmen came to light. The British viewed this as something much more serious that the tiff between Jan Slaai and the foreman, because the new authorities frowned upon the very idea of armed bands of civilians meting out justice in their territory.

The foreman, who committed the actual killing, naturally blamed Jan Slaai as the intellectual author of the alleged crime. Jan, in turn, defended himself by saying that he had obtained permission from the veldkornet. He also argued that, in any case, this new-fangled British notion that he should have gone and reported the theft to the nearest British authority (then located hundreds of kilometres to the South) was totally impractical. Because he rightly pointed out, by the time the British eventually arrived on the scene the stock thieves would be long gone and neither hide nor hair would remain of the animals.

The veldkornet, for his part (seeing the matter snowball and realising how the new wind was blowing), promptly denied that Jan had ever raised the matter with him. Which left Jan to carry the can and be made an example of.

Being a bearer of that obstreperous Steenkamp streak, Jan Slaai absolutely refused to pay the fine that the court imposed upon him. Which left the British with a dilemma, in that they couldn’t just drop the matter because they would then lose a lot of face. So, Jan Slaai was packed off to Robben Island. There he obstinately refused to recant and pay the fine. Which again became a problem for the British, in that it was costing them quite a bit to keep him there (what with the logistics problems that the island penitentiary had always presented).

Eventually Jan Slaai was bundled onto a boat and dropped off on the mainland, to find his way home. There being no trains those days, he basically had to walk all the way back. So that, one fine day, the family saw him come resolutely trudging down the ridge behind the homestead. According to family lore, his first words upon being reunited with his loved ones, was: “Waar’s my twak!?” (Where’s my chewing tobacco?)

My immediate forebears farmed on Elandsfontein, many kilometres south of Calvinia, towards Sutherland (the property is still being farmed by Steenkamps to this day).

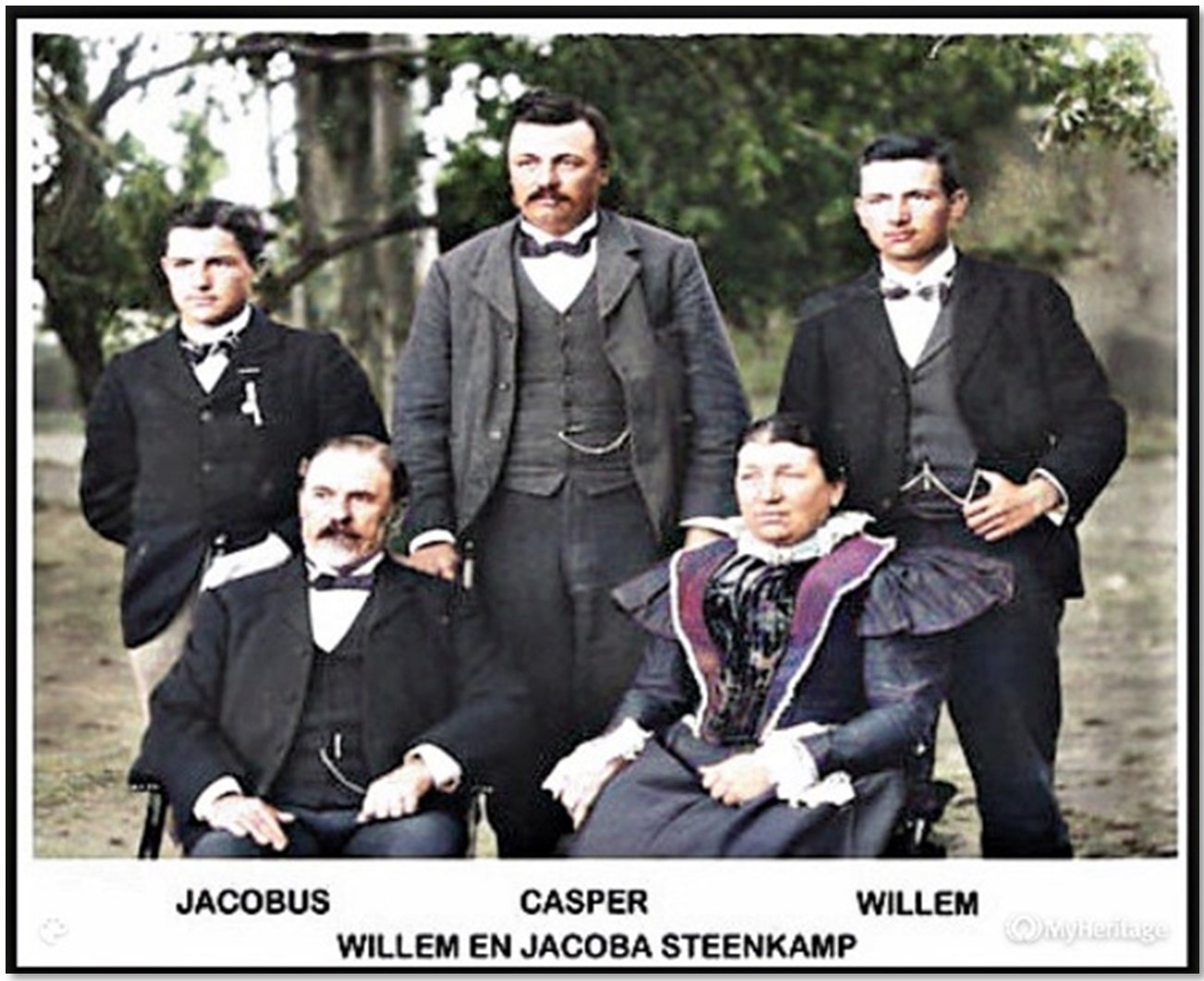

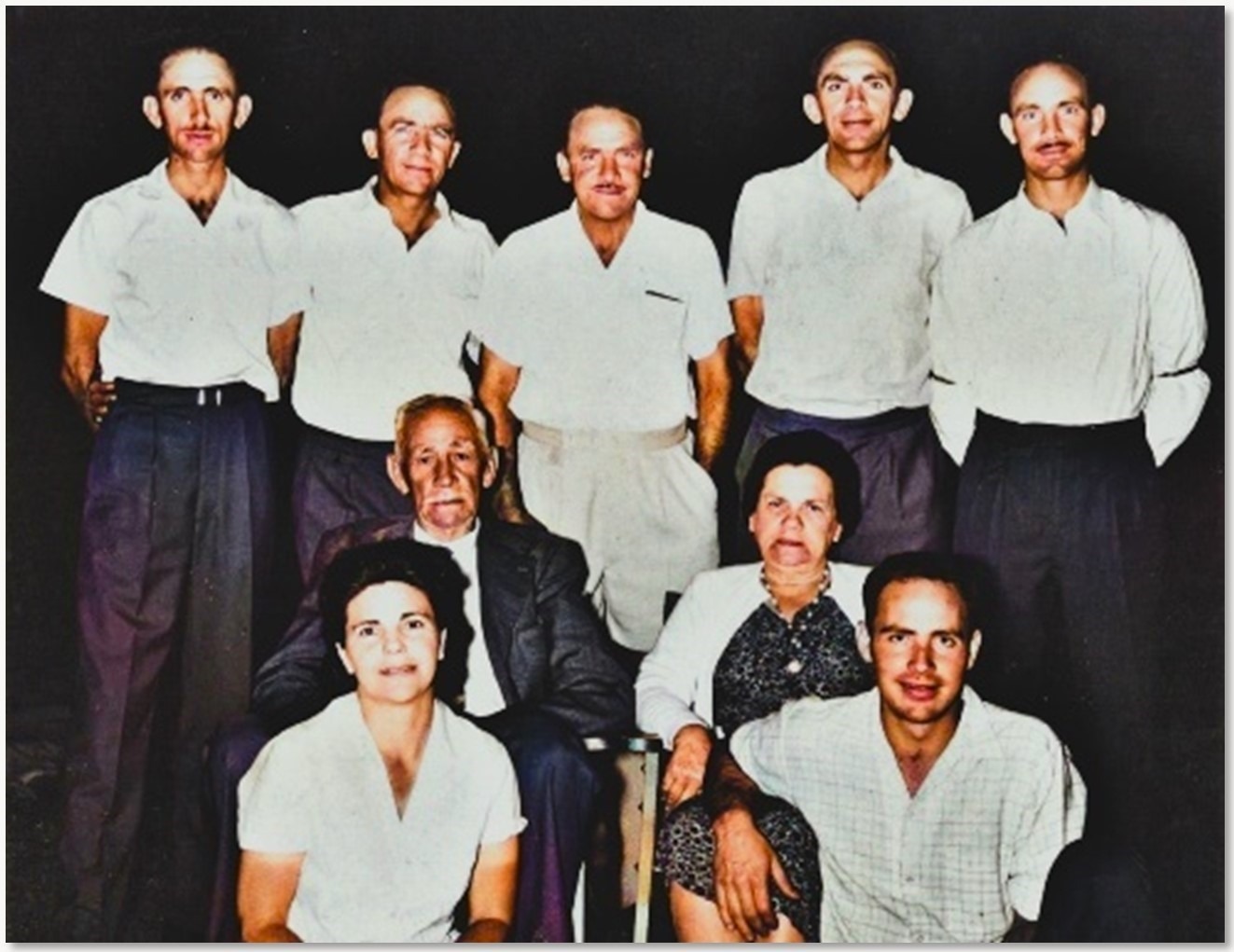

My great-grandfather Casper and my great-grandmother Harriet Sophia, nee Louw (of the nearby N.P. Van Wyk Louw clan) who both died young, are both buried on Elandsfontein. Their early deaths resulted in my grandfather, also Willem, growing up in the home of his deceased father’s younger brother, “Oudok” Dr W.P. Steenkamp. Here’s a photo of my great-great-grandparents, together with their three sons, with my great-grandfather in the centre back and “Oudok” Willem next to him:

2.2 My O’Reilly forebears:

Before I deal with my father’s generation of the Steenkamps, let me quickly introduce my fighting Irish forebears, the O Raghailligh (O’Reilly) of North-Eastern Ireland.

The O’Reilly clan were the rulers of the kingdom of Breffni (Breifne). Theirs was the only Irish kingdom to have minted its own coins, called Reillys. They were always known for their fighting prowess, especially their cavalry.

My branch of the clan had their family seat at Baltrasna Estate, near Oldcastle – located bout half-way between Dublin and Belfast.

Among the Baltrasna O’Reilly some of the best-known were Myles “The Slasher” O’Reilly, regarded as the “Braveheart of Ireland” for his defence of the bridge at Finca in 1646. Another son of Baltrasna was General Alexander “Bloody” O’Reilly who became famous as general and administrator under the Spanish crown. He improved the defences of Havana in Cuba, served as Spain’s captain-general (governor) of Louisiana in what is now part of the USA, and was appointed governor of Cadiz in Spain.

Below is a photo that I took of O’Reilly Street in Havana, marking the spot where Alexander came ashore to receive the city back from the British in 1763.

In 1776 there was born at Baltrasna, Anthony Alexander O’Reilly, who was to become a colonel in the British Army (a rare achievement for a pure-blooded Irishman at that time). He served with first the 4th Dragoons and later the 21st Light Dragoons. Colonel Anthony came to South Africa by way of India, was deployed in the Eastern Cape and eventually passed away in East London in 1870 at a ripe old age. His son John Robert O’Reilly, born in 1811, was also to become an officer in the British Army.

John Robert married an Afrikaans lady, Henrietta Hendrickz. He was among the officers who had received farms along the then Eastern Cape border in the vicinity of Graham’s Town, to serve as a buffer zone against Xhosa incursions. British governor Lord Charles Somerset however expropriated these properties, once developed with the sweat of the likes of John Robert. Somerset promised to provide in turn new land further North, which of course was undeveloped.

John Robert wrote a very eloquent yet forthright letter to Somerset explaining exactly what he thought of the esteemed governor, then packed his wagon and set off after the Voortrekkers, eventually settling in what is now Northern Natal.

John Robert’s descendants became Boere Irish, speaking Afrikaans as mother tongue. My great-grandfather James William O’Reilly became a well-to-do farmer owning a number of properties, among them the farm Gordon (on part of which the town of Newcastle was established). This farm abutted Fort Amiel, where the British had their field hospital during the 1st Anglo-Boer War.

The graveyard for the Redcoats who had succumbed from their wounds at the Battle of Majuba is actually located on our family farm named “Rusoord” (I remember well, playing there among the Tommy gravestones as a child). Another of the family farms was Duckponds, which became Newcastle’s black township Madadeni (duckponds in Zulu) plus a pastorage farm in the Drakensberg foothills called Leeds, on the road to Memel.

John William was a successful and innovative farmer – he, for example, won the gold medal for the best angora ram at the first Rand Easter Show held in 1895, as attested to in this clipping:

When the 2nd Anglo-Boer War came round in 1899, my great-grandparents were decidedly pro-Boer. My great-grandmother Maartens had many a scrap with the local British forces, leading to the family eventually being packed off to the British concentration camp in Pietermaritzburg. Here’s a photo of my very “gatvol” looking forebears, taken at the camp, with my own grandfather Tom the youngster in the funny hat on the right:

My mother would relate to me the conspiratorial atmosphere that prevailed around their farmstead during the 2nd World War, when my grandfather Tom would surreptitiously listen to the German Radio Zeesen in order to hear the “other side” of the news. I suppose that a confluence of Afrikaner and Irish blood, plus that stint in a British concentration camp, do go some way in explaining why one may discern a somewhat anti-English inclination among my O’Reilly forebears, even though they spoke perfect English (they were fluent not only in Afrikaans and English, but also Zulu – as was my father, who had also grown up in Natal).

2.3 Steenkamp and O’Reilly blood-lines unite:

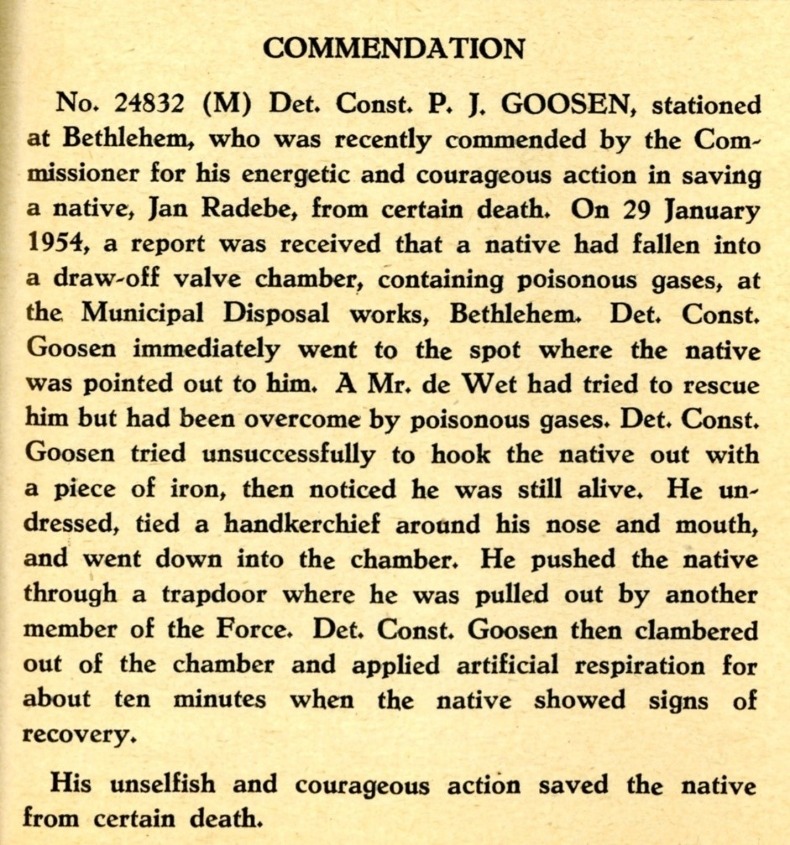

Back to the Steenkamps – because my great-grandparents on the paternal side had died young, my grandfather Willem was not a property owner and had to make do with his civil service salary as a cattle inspector. He and my grandmother had seven children – one girl, Harriet Sophia (Hetta), named after my great-grandmother nee Louw, and six sons, of which my father was the 2nd youngest. Despite being academically gifted, my father chose to leave school commencing Standard 9 because of realising the financial constraints the family were suffering in the aftermath of WW2. So, he fudged his age and joined the police (he later obtained five distinctions, when he did matric part-time).

My father fell in love with my mother when he was stationed at Newcastle as young constable. He was transferred to Durban soon after their marriage, where I was their first-born some three years later, on 16 December 1953 (the first time that the Day of the Vow was celebrated as an official public holiday). I always teased that, as a poor police family, my mother had to wait for a holiday to fit my birth in.

My mother, a very intelligent and well-read woman, stimulated my love for reading from before school age – I still fondly remember the title of my first book: “Vaaljas die eensame donkie”. She also stimulated my interest in current affairs, which she herself followed keenly on the radio. By age four, listening with her and being blessed with a good memory, I could name the presidents and capitals of all the then emerging new states in Africa.

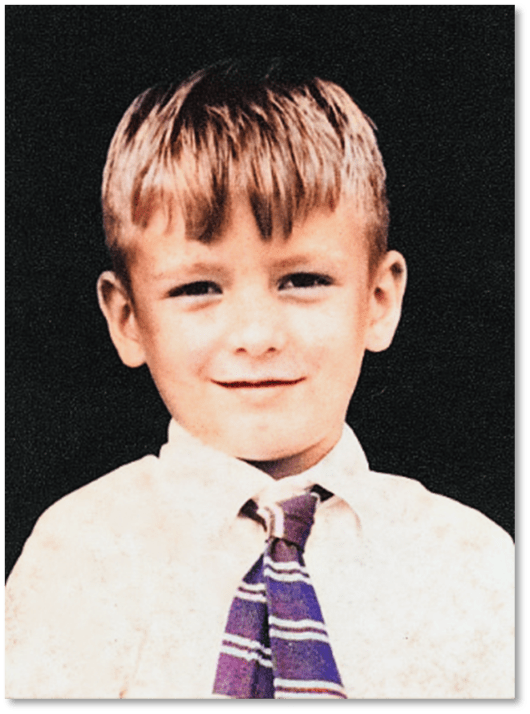

Below you can see me, in first grade at what was then the bi-lingual Montclair primary school in Durban.

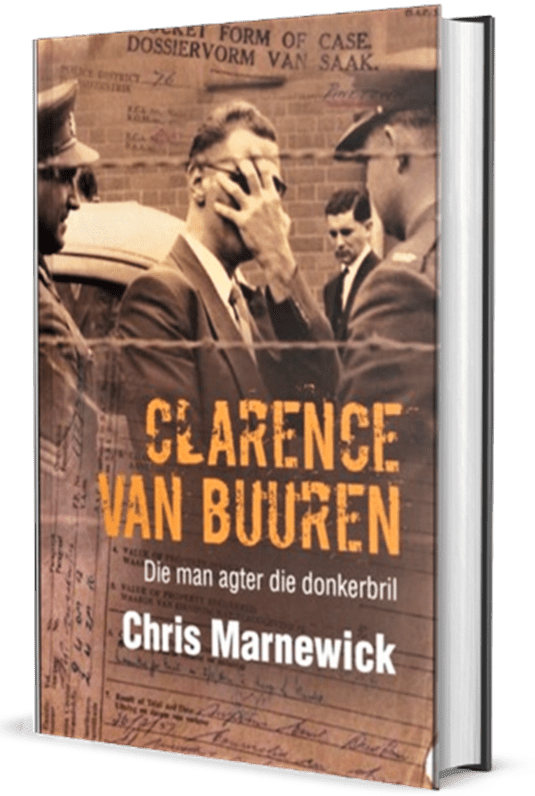

My father was at that time making a name for himself as young detective. His investigative skills made the headlines when he was handed the then stuck investigation into the high-profile murder case of Joy Aken, killed by Clarence van Buuren (the case was front-page news for months during the middle fifties).

The author Chris Marnewick later wrote a book about the case and there-in he calculated that my father had solved the matter within 29 hours and 5 minutes from having been handed the dossier. (See the cover of Marnewick’s book on the Aken case and the murderer, Clarence van Buuren, below – if you wish to read more about my father as described by Marnewick, simply click on the cover and you will be taken to a copy of the book’s bio-chapter on my father).

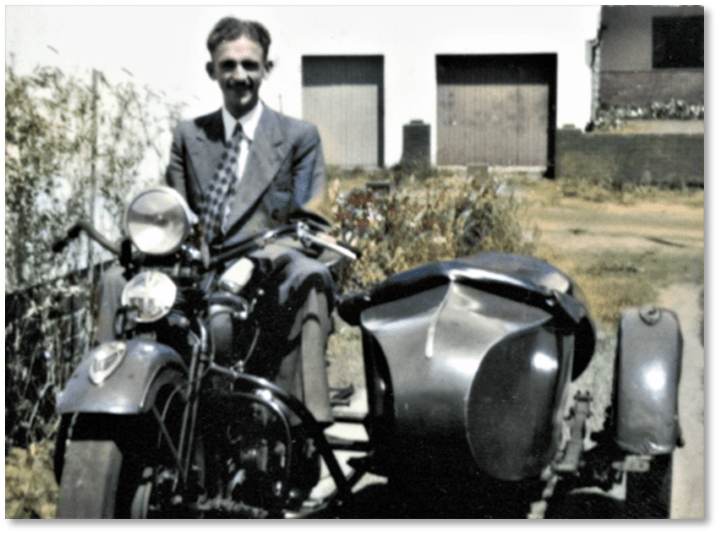

What I remember well from those early days, is my father’s official Harley-Davidson motorbike with sidecar, in which I sometimes rode with him to have my hair cut:

The Steenkamp clan gathered in Pretoria on the day of my father’s passing-out parade as a young lieutenant at the Police College in Pretoria. A memorable photo was taken that evening (what we in the family jokingly call the “ore-foto” because of how the then flash technology endowed them all with what appeared to be enormous, translucent ears!).

These Steenkamps were all servers of their country. My father (furthest on the left) came to head the SAP-SB; his brother Cor next to him served in the police before going into private business; the oldest brother Casper (named for my great-grandfather) was old enough to fight in WW2, where he was a sapper in North Africa; the 2nd oldest, Willem, became deputy director-general of Bantu Education; and Jan (or Koos, as we knew him in the family – furthest on the right) became commanding officer of Durban’s citizen force unit, the Regiment Port Natal, with the rank of Commandant, and obtained his parabat wings at middle age. Danie, the youngest (right front), was a member of the NIS and served as station head in Singapore and in Tel Aviv.

Talking about parabats in the family – my cousins Barry (son of Casper) and Johan (son of Jan) both jumped into battle in the airborne raid on Cassinga in Angola.

Apart from my interest in all kinds of sport (my mother was a very good hockey and tennis player and top athlete) and my love of going fishing, I was an avid reader as child, continuing my interest in current affairs, history, and politics. I had soon exhausted the limited Afrikaans junior section at our local municipal library in Fynnland, on Durban’s Bluff. So, I collected all the family’s library cards, (particularly those of my parents, that would give me access to senior books) and would walk up the hill, ten minutes from our home, to ostensibly take out books for them.

The kindly old lady at the library soon enough saw through my ruse but did not object when I would leave with six books at a time, consisting of biographies and books on history and geography. What did astound her, was that I would be back two days later for more of the same – this was how I rapidly expanded my reading ability of English, my general knowledge and my love for history.

This general knowledge stood me in good stead when, in matric, I could lead our school team to the finals of the SABC’s national general knowledge quiz for high schools. It also helped in making me articulate with both pen and tongue, so that we won the national debating contest for Afrikaans high schools in my matric year, in 1971. Here below, I’m standing with my team-mate and the trophies in a press photograph of the time (credit: Die Nataller).

I was fortunate to be awarded two bursaries – one a merit bursary by the University of the Free State (with no strings attached) for having won the debating contest, and the second a bursary from the Public Service Commission, which I eventually would need to work back by labouring in some government department after having completed my studies. With these bursaries, off I went in 1972 to study Law in Bloemfontein.

3: HOW AND WHY I JOINED THE INTELLIGENCE SERVICE

To understand how it came about that I joined the intelligence service (then called the Bureau for State Security – the BfSS) on 1 August 1975, a little bit of explanatory history is necessary.

After completing school in Durban at the end of 1971, I had enrolled at Free State University (as it is now called – at that time it was the University of the Orange Free State, and beforehand the University College of the Orange Free State, so that the Afrikaans acronym was initially UKOVS, leading to the students to be colloquially known as KOVSIES). The main campus is located in Bloemfontein, which city was also the judicial capital of South Africa during the Union and the later white Republic. It was the seat of the then highest court in the land, the appellate division of the supreme court (as it was known). Consequently, Bloemfontein and the Free State University Law Faculty enjoyed a very high reputation in legal circles. Because I wanted to study Law, Bloemfontein was thus my obvious choice.

Arriving at KOVSIES in January 1972 as a first-year student, backed (but also bound) by my bursaries – particularly the Public Service Commission one – an unexpected wrinkle appeared when I registered. Up to the year before, the local Law Faculty had followed what was then common practice in law faculties around the country, namely that an aspiring advocate had to first do a three-year bachelor’s degree (i.e., a B.A. or B. Com.), before then enrolling for the last two years for the Ll.B. degree (a Bachelor of Laws). Thus, five years in total. This is what my main bursary, that of the Public Service Commission, was based on: a five-year bursary for obtaining first B.A., then LL.B.

KOVSIES, however, that year upset the apple cart by wanting to elevate their Ll.B. to a master’s level, meaning that it would henceforth entail six years of study (3 for the initial B-degree, and then a further 3 for Ll.B.). They understood, though, that this could result in difficulties for students with five-year bursaries (like me), so they introduced also the option to do a five-year direct Ll.B., without the necessity of first obtaining a B.A. or B.Com. Obviously I opted for this direct 5-year option when I initially enrolled. Until the Public Service Commission intervened some months later, ruling: we gave you a bursary for B.A. Ll.B. and that is what you need to be enrolled for!

Unfortunately, they had only arrived at this conclusion halfway through the 2nd semester. Which meant that I urgently and very much belatedly needed to convince the university to change my registration. More importantly in practical terms, it also meant that I suddenly had to find another main course with which to fulfil the Arts Faculty requirement for the B.A., namely that you had to have two main courses each of three years duration (for the Law Faculty I had needed only one, namely Roman-Dutch Common Law, which fortunately could count as one of the two Arts main courses).

Because of my interest in current affairs, I opted for Political Science as my other main course, which I then had to start (and catch up with) even though practically half the academic year had already gone by. Fortunately, the head of the Political Science department also happened to be the dean of the Arts Faculty, prof. Herman Strauss. He was a wonderful person, very influential on campus, and he facilitated all the administrative arrangements. In the end I was also permitted to take extra subjects during each of my undergraduate years, so that I could make up for the extra year required for Ll.B. and could thus complete the course still in five years. This resulted in me obtaining my B.A. after three years with 16 course credits, instead of the usual 11.

By the time I had finished my undergraduate studies at the end of 1974 I was, however, thoroughly disillusioned with the whole teaching system, which seemed to me a huge waste of time. This was in part because the Law Faculty courses were, at that level, practically all presented as night classes only, in order to make use of senior practicing advocates of the high court as the lecturers (they were obviously excellent, but since they all had their day jobs as full-time advocates they could only lecture at night). Which left us students basically twiddling our thumbs (or playing billiards) during the daytime hours.

So, at the beginning of 1975 I decided that the obvious thing to do, was for me also to get a day job: meaning extra income to supplement my bursaries, and the opportunity to start working off my Public Service obligations (one year of work in a civil service department for every year that I had the bursary). Because I had to work in the Public Service at the discretion and pleasure of the Commission, and because of my legal qualification, I ended up being appointed as a prosecutor in the court of the Bantu Administration department in Bloemfontein (the erstwhile department then in charge of administering everything related to the Black African population of the country).

This mostly involved criminal prosecutions for transgressions of the pass laws (the bane then of the lives of all blacks, because it regulated where they could live or work) plus some civil law work as well, applying customary African law to family situations. South Africa then, and still today, acknowledges different legal systems, such as the Western model with its insistence on monogamy, plus then the Muslim and the indigenous African systems permitting polygamy – which explains why former President Jacob Zuma, for example, could have half a dozen legal wives.

To cut a long story short, I very soon realised that this kind of legal work did not appeal to me at all. Furthermore, I well understood that me working in the Bantu courts – even though it would shorten my years of working back my bursary to the Commission – was not going to meet my other need, namely, to get my compulsory national service behind me as well. For this, young white SA men had but three options: either to serve in a branch of the Military for two years, or join the police or the intelligence service.

Since the Commission only recognized the intelligence service, then called the Bureau for State Security (BfSS), as a pucca civil service department for purposes of my Commission bursary (the Police and SADF were excluded), the overlap I sought in order to be able to kill two birds with one stone, perforce meant that I had to join the BfSS.

Last but not least, the pay as prosecutor was lousy – R330 per month, which at the present exchange rate would be $16 (the Rand then had real value, being stronger than the dollar, thus the equivalent of $360 per month then) with the BfSS pay definitely somewhat better.

There were two additional reasons why I did not want to join the Police Force: firstly, because my dad was a senior officer (and I didn’t want any achievement of mine to be seen as if due to him). Secondly, my fiancé and I were planning on getting married in the foreseeable future. She had also studied with the aid of an academic merit bursary from the Welfare department, and also had to work for the public service in return. At that stage, the only department that would accept married women in full-time career positions was the Police. Luckily, Welfare did regard the Police as a government department for the purpose of her working off her bursary obligations. So, in January 1975 she had set off to the Police College in Pretoria for her compulsory initial police training.

Suffice it to say, with her also already in the Police and considering the then rule that husband and wife could not be employed in the same government department, the Police for me was, in that sense, also a no-no. As was the military, because I could see no value accruing to either myself or my country in me spending two years there scrubbing decks (I had been pre-assigned to the Navy).

Consequently, around mid-year in 1975 I applied for an official transfer from the Bantu Affairs Department to the intelligence service, the BfSS. After the necessary interviews, assessments, and security clearances, this was approved.

To my mind, this was a comprehensive solution: I could simultaneously work off my bursary obligation and national service, gain a better salary, and do work that was far, far more worthwhile and interesting than I had been doing in the Bantu courts, which I abhorred (or in the Navy, scrubbing decks!).

4. THE BUREAU FOR STATE SECURITY – WHERE & WHAT

4.1 Our offices:

Thus arrived my first day of labouring at the BfSS, with me presenting myself at the Concilium Building, on the corner of what was then Andries and Skinner Streets in the Pretoria city centre – the head office of the intelligence service, whose then name the English-language press had mischievously abbreviated to BOSS.

I was soon to realise that the complex consisted of more than just the 11-story Concilium building into which the main entrance had led; Concilium was internally interconnected on each floor with the adjacent Alphen Building, the latter situated on the actual street corner.

For the first year or so I was assigned to analytical Division “B”, which occupied a floor on the street front side of Concilium. In later years, when I was with analytical Division “K” (later to become Division “N23” when the Bureau was re-baptized to the National Intelligence Service), my office was on the 2nd floor of Alphen, just left of the corner suite on the photo below (see arrow).

Eventually, with my last promotion to the position of staff officer to the Chief Director for Analysis (N1) and deputy head of the central editorial division, I found myself back in Concilium, on the top floor. “N” stood for “Navorsing” in Afrikaans, meaning research – thus, the analytical branch of the service, responsible for evaluating the incoming information collected by the Operations and Technological branches, and processing it into intelligence products for distribution to decision-makers.

When, towards the end of my service, my request was granted to be allowed to gain operational experience as a “field worker” (i.e., running agents and collecting information, rather than sitting behind a desk and analysing it) I was transferred from the “N” branch to “O”, meaning Operations. To what would soon become the Chief Directorate Covert Operations, or Chief Directorate “K” (the Afrikaans for covert is “kovert”).

My last division, responsible for clandestine collection (i.e., the real undercover spooks) was housed in a nondescript incognito building in another part of the metropole, under cover of a dummy company. It was located far away from Head Office, which latter we were most emphatically prohibited from setting foot in. But more about that part of my career as the story of my years with the intelligence service unfolds.

4.2 Initial orientation and style of working:

At the time of joining the BfSS in 1975 the institution was but a few years old. The approach to training, then, was essentially one of “on the job” learning at your designated desk, interspersed with initial security and orientation training sessions then held somewhat ad hoc in the 11th floor auditorium cum conference room, when that was not required for meetings or for other presentations.

This was a temporary arrangement. The BfSS, especially as the later NIS, would soon have dedicated training facilities located outside Pretoria on what we called the ”plaas” (farm). These facilities would eventually grow into the very well-appointed campus of the National Intelligence Academy. During those early years, though, the training division still had to make do with the makeshift facilities of the conference room, especially when it came to the training of analysts and administrative personnel. This in no way detracted from the quality of the training that the excellent instructors offered, content-wise.

The initial orientation and security training we “head office types” (analysts and admin) underwent during those first six months on probation, served also as further assessment and selection, to confirm and make definitive one’s appointment – although I never heard of any new analyst who had passed the initial screening and security checks conducted before you were first admitted, not being confirmed. You were, for all intents and purposes, accepted as part of the team from the word go, perhaps also because of the dire need for qualified people to man the analytical desks at that initial stage. As an example of how thin we were spread – when I arrived, I was allocated to the “Coloured and Indian” desk, as its second (and only other) member.

Being so under-manned also meant that – within one’s division – there would be cross-allocation of tasks when emergencies cropped up, so that you may get roped in to help your next-door neighbours on the “urban black” desk, for example.

And emergencies there were soon to be a-plenty, when – from the middle of 1975 on – the peace that had reigned in the security sphere (after the SAP-SB had definitively put a stop to the sabotage campaign in the mid-sixties), suddenly evaporated overnight. In any event, the trends we were tracking and trying to understand, such as student unrest in the urban areas, didn’t play out nicely separated into Apartheid racial compartments. If there was student unrest, then it would manifest across our notional desk divisions, spreading among students of all racial groups, so that understanding and commenting upon it required a common assessment by the combined desks working closely together.

It was also typical of General Van den Bergh’s management style that he regarded it as important to communicate with his staff, in order to keep us all abreast of key trends and developments. He was not averse to calling “all hands” meetings, where he would personally brief us. Some among his detractors may say that it was because he liked to hear his own voice so much, but essentially it was to enhance team spirit (especially during crisis times) and to ensure that we understood the bigger picture, so that we could better understand where an how our own desk’s little pieces fit into it.

What I’m going to explain next about compartmentalization and restricting access to information, should therefore be understood against the background of this collegial management style – we juniors were not kept in the dark, even though we fully understood the need to always protect sources and methods.

4.3 Access to information:

The initial orientation sessions of necessity at first focused on security, explaining the system of compartmentalization of access to information based on the “need to know” principle – meaning, that each one only had access to just such information (particularly about operational matters) as he or she needed in order to be able to perform their assigned tasks, and to no more.

This compartmentalization was, in the case of the analytical desks, most relevant to information of an operational nature, such as collection methods and the identity of sources. This was most closely guarded. It stands to reason that, even though analysts would never see the name of a source listed in a field report received from the collections directorates (just the source’s allocated number), one could usually pretty quickly figure out from the context who source number 123 in fact is. It was thus drilled into us that all information related to operational methods and identities needed to be very sensitively handled on a strictly need to know basis.

On the other hand, what was shared were assessments of broader trends and knowledge of current events perhaps falling outside of your immediate desk description, but which could serve as useful, or even essential, background information to better understand trends on your own desk topics. This was so, especially within the divisions. (The BfSS was a small organisation at that time, particularly so in terms of the limited number of analysts in each analytical division; the typical working procedure within such a division was perhaps typically Afrikaans – similar to how our forebears conducted the Anglo-Boer wars with “krygsraad” meetings of all hands, where matters were discussed and points of view thrashed out round the table, with all opinions heard).

This principle of compartmentalization applied both to access to physical spaces and to data. Access to restricted spaces was indicated by colour codes, where-as to information it was tied in with the basic classification system for data, namely into four tiers: “open” or unclassified, “confidential”, “secret” and “top secret”. Doors to physical spaces were thus marked by colour – green would mean a space accessible to those with a confidential clearance, blue would mean a space into which only persons with a “secret” security grading may enter, and red would mean that you needed a “top-secret” security clearance to enter that particular space.

Combined, the two systems meant that you had access to spaces and data of a certain level of classification within your own division, but to another (typically lower) level of classification in relation to the data being stored in the intelligence service as a whole. Very few people were given access to “top secret” information on a service-wide basis; most analysts below the level of deputy head of division would have access only to the level of “secret” within their own division, and perhaps “confidential” at the service-wide level.

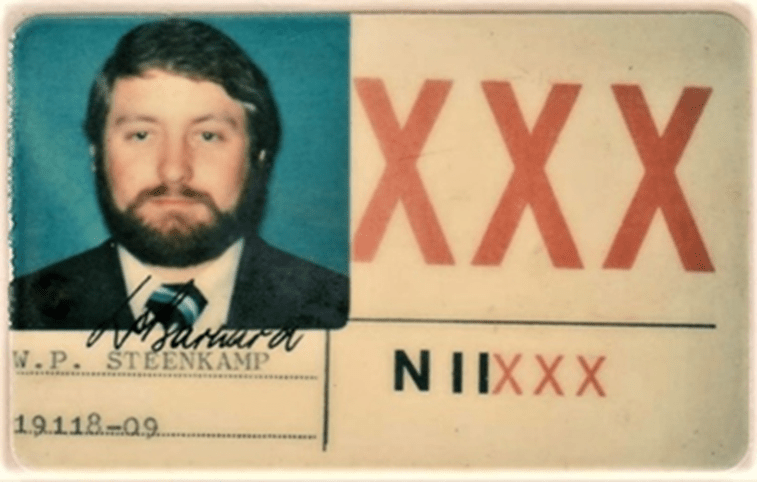

One’s authorized levels of access was indicated (during the existence of the National Intelligence Service into which the BfSS had morphed in the late seventies), on the identity card that each and every one of us had to wear at all times. Back in my own NIS days (i.e., prior to 1994, where-after the services were again re-organised) these ID’s looked like this old NIS card of mine – actually, my last card before I transferred from Analysis to Operations. (Since the new South African intelligence and security services of today have new, different ways of indicating access and identity, I’m not giving away any secrets here by showing what my card of more than four decades ago looked like).

On these old cards were indicated, to the left, the member’s initials and surname, as well as his service number. At the bottom right is indicated the letter designating your branch or Chief Directorate (in my case, “N” for analysis) plus then the number of your division (here, “N one-one”. This was derived from N1 being the designation for the Chief Director himself as head of the branch, with N11 (pronounced as one-one, not eleven) signifying that it was the division that served as the Chief Director’s personal support staff component and central redaction).

The three smaller red XXX’s next to N11 on the card, indicates that I had access to all “top secret” data within my division. The three big red XXX’s above, indicated that I had been authorised for access to all “top secret” data held anywhere in the service. (“Secret” would be two blue XX’s and “confidential”, one green one).

In the intelligence service we did not use military-style ranks and we wore civilian clothes (at Head Office, a formal dark suit was obligatory, in case we suddenly had to attend a Cabinet briefing or some such event involving the top ministerial echelons). We thus didn’t wear any visible insignia of rank.

Human beings being what they are, most people do have a natural desire to be able to fit others into some kind of pecking order of perceived seniority, status, or power (probably for self-preservation, so as not to inadvertently cross the wrong person). In the absence of visible military-style rank and insignia, these security clearance ID cards became the closest things to such visible indicators of stature in the old NIS. If you saw someone with three big red XXX’s displayed on his or her card, you knew that that person – no matter his or her age – was someone with high access, from deputy divisional head upwards.

When I wore the above card in the early nineteen-eighties (while then still being only in my late twenties), I was by a great many years the youngest member of the National Intelligence Service to sport those three big red XXX’s. I mention it here and show the photograph of my old ID card, simply in order to demonstrate to you that I did in fact have access to the high level and sensitive type of information that I will be sharing with you as we unpack “Our Story” during those critical years, despite my then tender age.

But, in relation to where I started out in the second half of 1975, that still lay a few years into the future.

4.4 How things were then in the South African intelligence community:

To understand the why and how of the manner in which “Our Story” would unfold, I need to talk here at the outset about more than just how the old BfSS functioned. I need to explain to you, as well, how the security and intelligence community then hung together (or, in fact, in practice very much did not!).

On the one side (let’s call it the theoretical side), there’s the legal framework as then established by parliament’s Act on Security Intelligence and the State Security Council of 1969. But, on the other hand, there’s the very different practical reality that existed on the ground… A reality of stand-offs literally with bayonets fixed, of bugging each other’s premises, of Military Intelligence operatives breaking into the safe of General Van den Bergh (he had inherited their offices – and safe – in the old Alphen building, so they knew their way about).

All of this went hand-in-hand with an increasingly fundamental (and heated) difference between PW Botha and the military on the one hand, and the BfSS, Department of Information and Foreign Affairs on the other, about the strategic direction that South Africa needed to take in the face of the rapidly changing world scene, especially as it was then quite dramatically manifesting in Southern Africa.

This debate on strategic direction would come to supersede in national decision-making importance, the mere ideological issues about race and democracy that were playing out in civil society at the time, under banners such as “verkramp” versus “verlig”. As the security “deep state” rose in importance and influence (in parallel with, and because of the ever escalating threat level), this intra-security struggle for supremacy regarding strategy would increasingly determine the country’s direction, budgeting priorities, and public posture over the next two decades. This debated revolved around whether the best strategic option was to aim to settle, or to prepare to shoot things out.

Suffice it to say that there was intense dislike between PW Botha and Lang Hendrik van den Bergh – that is, between premier Vorster’s defence minister and his security advisor. PW Botha, notoriously thin-skinned, regarded himself (as Cape NP leader and cabinet minister) well above a mere civil servant, and thus resented Van den Bergh’s access to the prime minster. Especially so, because Pieter W Botha (whose nickname was “Piet Skiet” – Piet shoot) was firmly at the head of the “shoot” school of thought, which saw those counselling that a settlement be sought as appeasers.

The proverbial fat landed in the fire when the Military Intelligence operatives that had opened the safe that Van den Bergh had inherited, found inside a file on the self-same PW Botha. The latter was besides himself because of what he perceived as the temerity of this. What he clearly did not understand was that it was normal (and essential) practice the world over that intelligence institutions would have such files.

This was due to the fact that cabinet ministers were clear targets for hostile services. Being human, they could unintentionally get themselves into trouble – just recall the scandal around British minister John Profumo and the KGB-linked call-girl a few years before. Or another prominent South African cabinet minister also with the surname Botha, a few years later (which story I will come to in good time…).

What was a common practice the world over in such cases, is that these sensitive files would not be kept in the Central Registry, but in the personal safe of the head of the service. J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI was a well-known example of having done this. The purpose was in fact to protect the subject of the file, firstly so that its mere existence isn’t picked up by staff simply because of it being kept and indexed in a Central Registry, and secondly to better protect the sensitive content.

I don’t know what was in Botha’s file and have never seen its content mentioned, but in any event, PW Botha took extreme umbrage and insisted to Vorster that Van den Bergh be immediately fired. Vorster, always keen to keep his people united, found himself in the middle (not for the first time, and unfortunately not for the last either, as I shall later point out). He did not fire the tall general but was eventually forced to appoint a judicial commission under judge Potgieter to try and resolve the structure and divisions of labour within the intelligence community, about which so much inter-departmental strife had persisted after the founding of the BfSS.

Even this exhaustive and well-researched report did not, alas, put a stop to the in-fighting, turf wars, silo practices and empire-building within the security and intelligence community – particularly not the fundamental dispute about strategy between those who saw it as imperative that a settlement be sought in time (with Vorster himself having called the alternative to settling “too ghastly to contemplate”) and those in especially the Army (i.e., land forces – who we called the “brown shoes”) who saw a military stand-off as inevitable and wanted every effort and every budget cent to be directed at preparing for such a shoot-out.

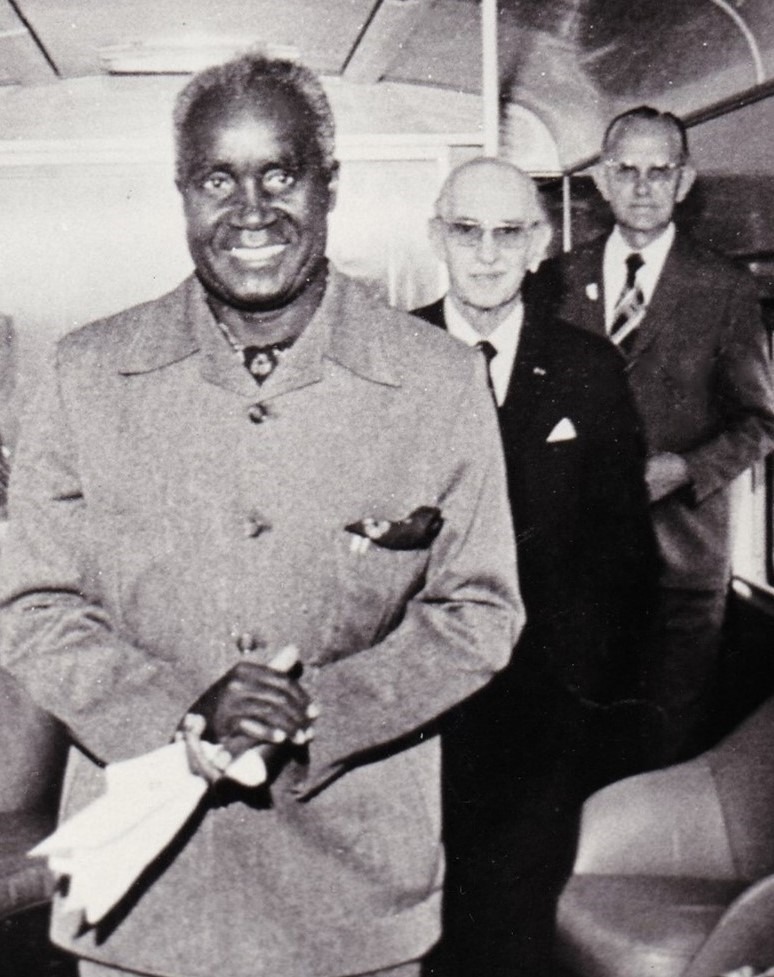

When I arrived at the BfSS in August 1975, the efforts by premier Vorster and General Van den Bergh to facilitate a negotiated settlement in Rhodesia (as part of South Africa’s general détente outreach to black Africa), was at its zenith with the 26 August summit held in a train parked over the Victoria Falls bridge. President Kaunda and Vorster co-hosted the negotiations, attended by Rhodesian premier Ian Smith and internal black leaders.

Within weeks, however, actions taken unilaterally by PW Botha and the Army and which ran directly counter to what the BfSS were vigorously counselling, would decisively change the security and diplomatic environment in the region and effectively deal a death blow to détente. I will discuss this critically important “fork in the road” in detail a bit later, but first I want to share with you some background about my formal training as an intelligence officer.

5. TRAINING TO BE AN INTELLIGENCE OFFICER

The training I received can be divided into three phases. Firstly, there was the initial orientation and security training undergone by all newcomers (back then, in the 11th floor auditorium). That was followed by the different levels of line-function training (in my case, with main focus on intelligence analysis – this was conducted at the training complex on the rapidly developing “farm”. Lastly, the training I received abroad, at the German Bundesnachrichtendienst in Munich.

5.1 Initial security orientation:

As said earlier, the initial training at the then BfSS during those early years of the existence of the intelligence service, was presented in the auditorium on the 11th floor of the Concilium Building. The Training Division would, however, soon thereafter move to the “plaas” (farm) to the east of Pretoria, where over the years an attractive, well-equipped modern campus was developed for what was then already morphing into the excellent National Intelligence Academy.

The entry-level training courses were short and were attended “off your desk” (i.e., intermittently, interspersed with undergoing what was essentially “on the job” training). These initial sessions were aimed at general orientation and security, and were obligatory for all newcomers, no matter whether they were line-function intelligence officers or administrative support staff such as typists. Counter-intelligence was a particular focus, to sensitize each and all to the threat of a hostile service or entity trying to recruit them.

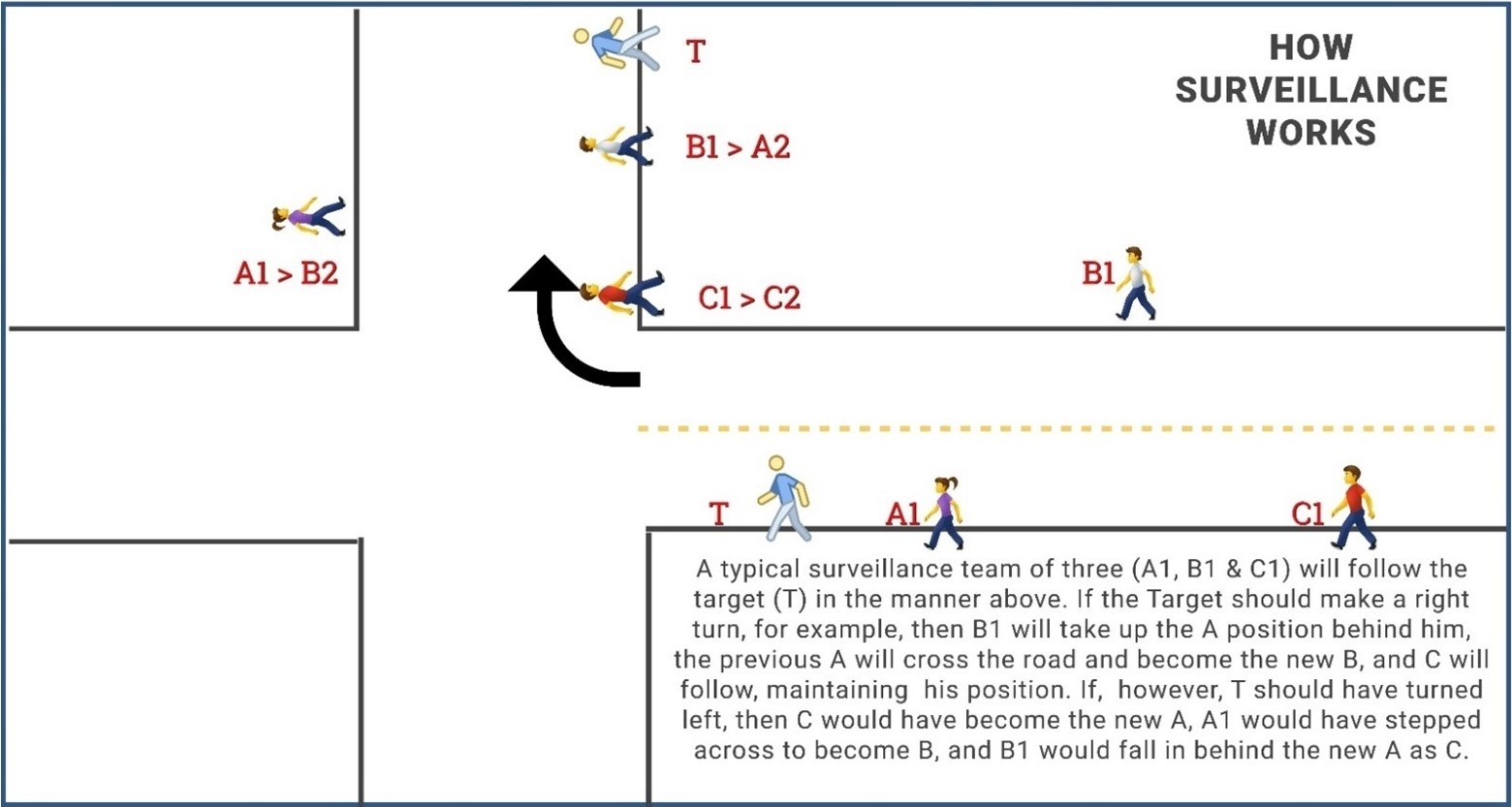

The typical methods and inducements used by hostile services were explained. This was mostly done with the aid of training films developed by the British and Americans, based on case studies of Western/NATO institutions that had fallen prey to such attempts at infiltration and recruitment (mostly by Warsaw Pact spy agencies, particularly the Soviet KGB and their military intelligence, the GRU, and the East German STASI).

Another aspect of the initial training focused on maintaining the physical security of the BfSS Head Office complex (i.e., Concilium/Alphen buildings). All male staff were obliged to perform night-time security duty at the complex, on a rotating schedule. This entailed manning (as a two-man team) the security operations room, to monitor the surveillance system that covered the property perimeter, and intervening as armed guards, should anything suspicious be noticed. This duty would befall one for a few nights every couple of months. Consequently, we all thus had to undergo weapons training, so as to be able to safely and accurately use the Israeli Uzi sub-machine guns which the security duty team had at its disposal.

The “farm” of course had a proper shooting range, complete with built dummy structures of buildings for practicing “room clearance” (i.e., for when hostiles had managed to enter the building and had to be eliminated within the built environment of offices and hallways). Also, “friendly” and “hostile” man-shaped movable and pop-up targets, to ensure that you learnt the necessary self-control regarding who to shoot at, and who not.

The main challenge that we all faced in this specific weapons training (and also when on actual security duty!), was the notoriously poor reliability and gun safety characteristics of the %$++!! Uzi. It was famously light-triggered and delicate, prone to going off by itself at the slightest bump. We therefore joked that the best way to do such room clearance (if confronted with hostiles holed up inside an office or room), would be to grab the Uzi by its short barrel, swing it a few times over your head and then chuck it spinning into the room – it was a sure thing that the moment it struck the floor or a wall, it would go off by itself, letting loose its entire magazine, thus randomly spraying the entire interior with bullets and hopefully putting paid to the intruders…

That this wasn’t an entirely fanciful notion was demonstrated one morning at Concilium’s main entrance. It was standard practice that, between seven and eight in the morning when the bulk of the day-staff would be entering the building, one of the security team on duty, with Uzi and all, would be present there in the background – just in case some sly intruder tried to seize that opportunity with everybody crowding in, to try and make an entry. The particular guy on duty with the Uzi that morning was a manual labour assistant in the print shop (we had a full, sophisticated printing press in the basement). With all due respect, whereas he was excellent at his job, he wasn’t the sharpest pencil in the pack when it came to things like gun handling.

It happened towards the end of the rush, when only the laggards were still pitching up and the day’s business had already commenced. The guy pushing the secure steel trolley conveying classified documents from one section to another under lock and key, just happened to pass by. At that moment our printer’s assistant somewhat carelessly had put the Uzi down on the top of the counter that ran the length of the entrance hall.

This treatment, not ungentle at all, was enough to immediately affront our dearly beloved Uzi sub-machine gun, which let off a solitary round in response (it had fortunately been set to single shot). Which struck the poor guy pushing the document trolley – luckily, in the buttocks. So that he spent some uncomfortable weeks recuperating but had not suffered any life-threatening injuries. Since he was somewhat of a hypochondriac, this provided our survivor hero with substantial fodder for sharing his lot with all and sundry – almost as if it was a godsend for him, giving him a certain stature, plus sympathy of course. And, for once, something real to complain about.

What was most awkward when doing the night-time duty, was that the Uzi then had to have a huge, bulky spotlight mounted on its bayonet lug. This spotlight was indeed very powerful, but the weight of it and its battery completely unbalanced the thing (at least the battery then served as an extra hand grip).

The bane of our lives at night were the stray cats that roamed that part of town as soon as darkness fell. They would regularly trip the necessarily sensitive perimeter sensors, requiring us to go out on eyeball inspection with the Uzi at the ready. The fact that no-one ever let loose a volley at one of those nefarious nocturnal nuisance-makers where they crouched, as if paralyzed, when caught in the glare of that powerful spotlight, attests to the responsibility, patience, and self-discipline of my colleagues.

5.2 Line Function Intelligence Training:

Once having finished with the general orientation and security training, we embarked on our line-function intelligence training. This training was divided up into progressively more advanced levels, presented successively at intervals of a few months, so that practical experience could in between be gained on an analytical desk. It again started out with a now more detailed introduction to the broad basics of intelligence as craft, and then, as you progressed through higher level courses, focused on your field of specialization – in my case, intelligence analysis, meaning the evaluation of the degree of veracity of the information that had been collected by the operational branches and its processing and interpretation into finished intelligence products to be disseminated to decision-makers.

My Level 1 line-function course was still presented in Concilium’s 11th floor auditorium (i.a. to be able to use its screens and projection facilities). Our training officer was a true gentleman who’s name I still recall clearly to this day – Henry Deacon. Apart from what we as trainees would be learning, the course also permitted our instructors (and thus, the service), to learn much about our individual aptitudes and abilities – an evaluation process that they were constantly engaged in, and which saw them reporting back on us to our bosses.

This initial level of line-function training was designed to be a further, more detailed introduction to the world of intelligence. It was designed to allow us to understand and appreciate the operational environment in which information was collected in that pre-digital age. This I personally found fascinating and stimulating (as I suppose most people would). I thrived because it was practical. It challenged one’s “can do” ability and capacity for lateral thinking (rather than the abstract academic stuff of one’s student days).

I’ll recount here two instances from that training, with two objectives. Firstly, to show you the type of stuff we were challenged with, illustrating therewith the kind of training exercises employed and the underlying brain-centred approach of stimulating analytical thinking and problem-solving ability (which was a somewhat different approach to what I know the security police training, for example, typically consisted of).

My second objective with citing those long-past events is to present proof to you of why I ended up in positions of responsibility at a young age, which allowed me to observe important developments first-hand from particularly advantageous vantage points (thus, I’m quoting these training incidents here for reason, not because I simply wish to blow my own bugle!)

In a nutshell, throughout my intelligence career I consistently came top of class, by quite some margin. Which was duly noted by the powers-that-be and helps explain why I was entrusted with sensitive tasks from early on in my intelligence career age. (This would be a reality that would later repeat itself at Foreign Affairs, where I also ended top of the class by a margin of nearly 11% above #2, and which soon led to me being entrusted with positions such as heading the diplomatic academy and then being nominated as ambassador at age 38 (more about that in Part Three).

There were two specific exercises during that initial training where I had caught the particular attention of Henry Deacon. One was a problem-solving test of creative, lateral thinking (we did a lot of such mind-stimulation exercises). It entailed each of us being issued with a bunch of identical cheap kitchen forks and two empty Coke bottles each. We were then challenged to construct, with those forks, a sturdy and reliably self-balancing bridge between the two bottles, which had been placed apart somewhat further than the length of an individual fork – easier said than done!

I must confess that I found this exercise quite a challenge, in part because I soon noticed that Deacon seemed to take a special interest in my experimentation with my set of forks. My level of perturbation would continue to steadily increase as I struggled, because he would look somewhat askance at my stop-start efforts, shaking his head.

Henry obviously knew the textbook solution, and the one I was trying to come up with was clearly far from it.

However, he became more intrigued as I progressed, with me persevering till I had my “bridge” set up and stable. Henry tested the cantilevered “bridge” which I had, by trial and error, created – and then remarked with some wonderment to me that I’ve found a new way of doing it. According to him, mine was actually sturdier than the supposedly unique solution described in the book…

The other test that still sticks in my mind, was of our powers of observation. It entailed flashing images of typical street scenes onto the auditorium’s big screen from a slide projector – but just for a fraction of a second. The projector was fitted with a reversed SLR camera lens shutter, allowing variable shutter speed settings to be used. In other words, adjusting for how long the lens is kept open to allow light to pass through. The way it was being used in reverse on the projector, it controlled for how long the slide image would stay on the screen. With typical shutter settings, this could be as little as 1/1000th of a second. In layman’s terms, for no more than the duration of that distinctive “click” one heard when pressing the shutter button of those old pre-digital cameras…

When Henry started this exercise, he had set the shutter at its fastest. He had warned us to be alert; that we were supposed to mentally take in the scene that would appear on the screen, and that he would then ask us questions about it – not explaining, though, that it was going to be on screen for just a flash. So, when that image (it was a street scene with motor cars) stayed on for less than the blink of an eye, everybody was somewhat befuddled when he asked us for the plate number of the frontmost car in the image. From his past experience with previous training groups, Henry had obviously anticipated this bewildered response and was equally obviously enjoying the dumbfounded reaction he had elicited.

Until I – precocious as ever – called out a plate number.

Now, I am blessed with a very good memory, and – at that stage of my youth – also with quite acute eyesight. So, I tried to recall the scene in my mind, and sort of “read off” the number from the image I had retained in my head. (I must admit that I loved training sessions and would get really involved, always piping up – and I didn’t see any harm in at least trying my luck!).

Henry was quite astounded that somebody was actually venturing an answer. He quickly checked his notes, and again with some wonderment exclaimed: “You know what, you’re actually right!” He sort of began to ask whether perhaps some previous course group had alerted me to this exercise and had given me the answer beforehand, but from my affronted reaction he could clearly see that it was not the case. So, he confirmed that, in his experience as training officer, I was the first person, up to then, to have been able to correctly recite the plate number off that “first flash”.

What this contributed to, was that my aptitude for field work was duly noted on my personnel file, which stood me in good stead when I later applied for a transfer from analysis to operations…

The next levels of more advanced training in the art and science of verification, evaluation, and interpretation of intelligence, I received on the “plaas” – the complex discreetly located in the agricultural area to the east of Pretoria. The modern Intelligence Academy campus had not yet been constructed when I did my line function training there. The lecture rooms of my time were flimsy prefabricated structures similar to what the Department of Education would erect at many South African schools as temporary classrooms.

The “plaas” was located at an elevation of about 1,600 meters above sea level, on a very exposed ridge subject to the freezing winter winds blasting through. So, those “prefabs” were cold. Damn cold. Especially when a cold front passed through, and the early morning temperatures dropped below zero. I remember us sitting there, shivering, our shoed feet wrapped up in our rugby jerseys (wintertime being rugby season, so for the Wednesday afternoon games of the mid-week inter-departmental league, we would bring our kit along to class, to have it to hand for a quick change in the afternoon).

The warmest spot was actually outside, on the north-facing side of the prefabs, where the building provided shelter against the chill of the southerly winds and formed a kind of reflective sun-trap off its light-coloured walls. There, the flock of the Farm’s overly numerous peacocks and peahens would then gather to sun themselves. Anyone familiar with the obnoxious honking sound that these creatures make (horrendously loudly at that), can imagine the effect inside those prefabs with their thin walls, when that bunch started sounding off right outside…

The first phase of the analytical process was to assess incoming information for its validity, and then accord it an alpha-numerical ranking on a six-point scale, so that others handling it later in the process would know how much credence to attach to it. This was done by considering the reliability of the source (if it was a human) and by evaluating the content against the matrix of other available information on the topic its content covered.

The perceived reliability of the source was expressed by means of an alphabetical scale from A – F (with A being proven reliable, and F being “of unknown reliability”).

The information as such was rated for credibility on a numerical scale, from 1 – 6, with 1 being proven by means of confirmation by other sources and information, to 6 which meant that the information could for the moment not be rated, due for example to it being a totally new input on the subject matter, with no basis for comparison with other related information. The table below explains in more detail how this works:

Source reliability

|

Rating |

Description |

|

|

A |

Consistent reliability proven |

No doubt about the source’s authenticity, trustworthiness, or competency. Proven history of complete reliability. |

|

B |

Usually reliable |

Minor doubts. History of having in the past provided mostly valid information. |

|

C |

Fairly reliable |

Some doubts. Provided valid information in the past (but not always). |

|

D |

Mixed, tending usually to not being reliable |

Significant doubts. Only sometimes provided valid information in the past. |

|

E |

Record of usually being unreliable |

Lacks trustworthiness. Past history of peddling invalid information. |

|

F |

Reliability unknown |

Insufficient information to evaluate reliability. May, or may not, be reliable. |

Information credibility

|

Rating |

Description |

|

|

1 |

Confirmed by independent Sources |

Logical, consistent with other relevant information, confirmed by independent sources. |

|

2 |

Probably true |

Logical, consistent with other relevant information, but not confirmed. |

|

3 |

Possibly true |

Seems reasonably logical, agrees with some other relevant information, but not independently confirmed. |

|

4 |

Doubtful whether true |

Not logical but possible, no other information on the subject, not confirmed. |

|

5 |

Improbable |

Not logical, contradicted by other relevant information. |

|

6 |

Not possible to assess |

The validity of the information cannot be determined. |

Once the incoming item of information had been evaluated for its perceived validity, it had to be analysed and contextualized for its significance and meaning; in other words, it had to be interpreted and woven into the holistic intelligence picture. With this done, it had to be incorporated into the service’s intelligence products (i.e., printed briefing documents, somewhat like a special kind of “newspaper” for selected eyes only), produced with the purpose of being presented to national decision-makers to appraise them of threats and opportunities in timely manner.

Intelligence products can range from the daily kind, such as the CIA’s daily brief for the president of the USA, to annual threat assessments – what we called the N.I.W. (the National Intelligence Assessment, in English) which annually assessed the security situation of the country on a holistic basis, including inputs from all government departments – especially the diplomatic service, the Security Branch of the SA Police, and Military Intelligence. By law, in South Africa’s case, the production of this comprehensive annual assessment of typically around 200 pages in length was an explicit legal obligation. It was coordinated and led by the Bureau for State Security and its successors.

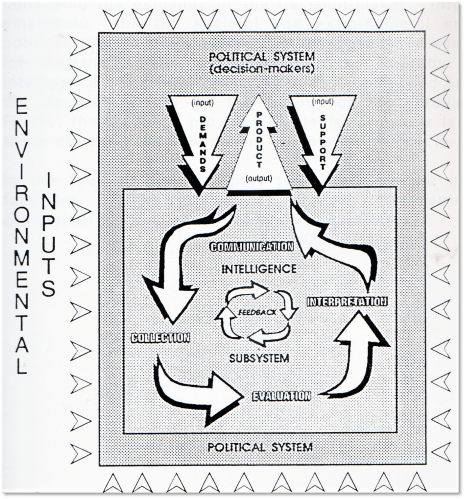

The process of producing verified, interpreted intelligence is known in the profession as the “intelligence cycle”. In my doctoral thesis (titled “The Intelligence Function of the Political System”) I developed a schematic representation of this, which is copied below.

5.3 My Training in Germany with the BND:

The last intelligence training course I attended was presented by the (West) German Bundesnachrichtendienst, in Munich. In part it was a relationship-building exercise as well. These professional ties demonstrated how tightly “Apartheid” South Africa was then still held close by the West in the areas where it mattered, such as intelligence and defence – even if done covertly rather than openly (all of it driven, of course, by the West’s then fear of the Red Bear, there at the beginning of the eighties coming off the Soviet Union’s earlier gains in places like Vietnam).

This BND training was an annual thing, presented for a group of about a dozen NIS analysts at a time. The lectures were given in a well-appointed BND “safe house” in the suburban outskirts of Munich, with the lodging facility being another equally well-appointed safe house that was set up like a luxury guest house or boutique hotel, replete with discreet service staff and an excellent chef.

These annual training / liaison events were always presented for us South Africans during the famous Oktoberfest (which actually takes place in September, not October). The Germans would have us believe that this was due to prioritizing us among their partner services, to make it as special as possible for us. This probably was true, because the interpersonal relationships were indeed very cordial, but we also understood that inviting us at that time, with the city flooded by foreigners, would make us “lepers” stand out the least…

Inside the city we were treated to trips to the Royal Palaces and historical sites such as the Hofbräuhaus beer hall, from where Hitler had tried to stage the putsch that saw him briefly jailed in the twenties. There were also trips to the Alps and the famous castle of Neuschwanstein.

The very first day’s lunch, though, was a “must impress” effort, with all stops pulled out by our kind hosts. It was offered to us in the superb Bayerischer Hof Hotel’s private dining room, which they were proud to point out was the favourite haunt of Bavaria’s then famous and popular minister-president Franz-Josef Strauss, who had been an unapologetic open supporter of South Africa and a frequent visitor to our shores. The meal, unfortunately, was typical German cuisine of pork and potatoes, and (although prepared to perfection) wasn’t really a culinary tour de force as far as my tastes were concerned…

Perhaps the most memorable meal for me, during that trip, was a dinner in a restaurant in the old part of Schwabing, the artists’ and students’ quarter in the northern suburbs of Munich. Not only was it the best pepper stake I’ve ever had (to this day), but I was particularly struck by an invented tale that one of our BND hosts had re-told that evening.

The story (which it was said is often re-told among Germans to illustrate the vagaries of history, as well as to demonstrate that change is the only constant in life) was about a group of proudly patriotic German students who, at the dawn of 20th century, had cornered a wise old sage who was supposedly able to foretell the future. They wanted to hear from him what the future held for Germany, which at that stage – at the beginning of the 1900’s – was very much on the up-and-up after its unification just three decades before.

The old man reflected a bit, seeing with how much positivism and enthusiasm they were anticipating a bright future for their country.

“There will be ups and downs…” he eventually replied a bit warily, hesitating to share what he had seen.

“Please tell!” the youngsters pressed him.

“Well, by the beginning of the next decade, the early 1910’s, Germany will be even more wealthy and powerful than we’re now already, with a strong, growing navy and expanding colonies around the globe. People will be living well, and life will be good.

“However, by the beginning of the next decade – the early twenties, that is – we will no longer have a Kaizer, we will have lost more than two million men and much of our territory to the Poles, the Czechs, and the French in a four-year war that will have engulfed practically the entire world, and we will have an impossibly huge war reparations debt to pay to those who had conquered us.”

The students were naturally very uncomfortable hearing this, and wanted to know if things would then at least start picking up again?

“Unfortunately, no” the sage replied. “By the early part of the thirties, our economy and that of the world will be in dire straits. A great depression will have descended on the planet. You will need a wheelbarrow full of Deutschmarks to buy a loaf of bread, and unemployment will be rampant. Furthermore, a madman Austrian corporal will be politically on the rise in Germany, taking over the country by nineteen thirty-three…”

By this time, many of the students were beginning to very much doubt this supposed sage with his extraordinarily improbable-sounding predictions. “Then surely we won’t recover from that and will just be heading further down” one remarked.

“No, no” the sage replied. “On the contrary – at the beginning of the forties, our beloved Germany will be Europe’s greatest power. We will have defeated the French and the Poles and will have our troops controlling everything from the North Cape in the Arctic down to most of North Africa.”

This perked up the students no end. “So, from then on things will be great again, won’t it? We’ll just go from strength to strength!” the sage’s young inquisitors postulated.

“Alas, no, my young friends” the sage replied sadly. “By the early fifties our great cities will be in total ruin, with our country again reduced in size, much more so than even the last time. We will have lost more than four million of our soldiers in that 2nd war and we will have on our national conscience that we had murdered more than six million Jews…

“We will be under full military occupation, with the country divided into occupation zones by our conquerors, and with East and West Germany separated from each other. We will have suffered massive economic destruction and devastating civilian…” By this time, though, before he could even finish, the last of the students had gotten up and stepped away from the supposedly clairvoyant old sage, in utter disbelief at the “totally ridiculous” future scenarios that he was trying to make them believe would actually transpire…

We know, of course, that every “prediction” in this fictitious story actually did come true. All that I can say today, is that (judging from my own life experience), the only constant that one can count on as a sure thing, is indeed ever-present and unpredictable change.

Which is why one must always beware of assumptions…

That somewhat ironic story had made me think deeply, back then. About the “constants” which we were then assuming to exist (there at the beginning of the eighties), and believed would be ever-lastingly “immutable”. Such as the Cold War lasting on and on, as the defining paradigm of our times. And, ever-lasting white rule in South Africa…

The training we received in Munich was very much marked by the anti-communist Cold War context. The Soviet Union and its spy agencies were public enemy number one, for both us and them. A lot of briefings thus dealt with the internal structure of the KGB, as well as the military threat emanating from the Warsaw Pact.

Just like the NIS, the BND was also a full-spectrum agency, meaning that it monitored and reported on all domains that could impact national security interests. It therefore also had specialised analytical divisions for assessing economic, military and political developments in the East Block – again, just as the NIS had its specialised divisions focused on analysing economic, military and political developments within our primary Southern African geographic sphere of strategic interest. In fact, the BND had primary responsibility for military intelligence at the strategic level in the German system.

Obviously, the Germans aspired to have their country re-united. What I remember vividly, is the official maps that they had stuck on the walls in the lecture rooms – these depicted Germany’s borders as they had been after the First World War, with the former East Prussia accordingly then still indicated as part of Germany…

The lectures weren’t varsity-style classes, however. There was a lot of conversation around these topics, with the Germans sharing their many run-ins with the Russians, giving practical content and a good dose of reality to our interaction. The Germans were perhaps best placed of all the NATO members to share this kind of real-world experience regarding the Soviets, due to their first-hand knowledge going back to the German need to prioritize the Eastern Front during the war.

The BND was actuality born out of the WW2 German Wehrmacht’s military intelligence division focused on the Eastern Front, Fremde Heere Ost (literally meaning “foreign armies east”), with FHO having been a part of the Abwehr, the wartime German military intelligence organisation.

FHO was during the latter part of the War under the command of General Reinhard Gehlen, who had the foresight to keep his men and archives together and then offer them to the Americans (who were the occupying force in Bavaria), as a package deal. The Americans jumped at this and put the now “Gehlen Organisation – Gehlen Org” immediately to work to keep spying on the Soviets, doing so from the former Nazi Party headquarters complex at Pullach in the outskirts of Munich, which the Americans had turned over to Gehlen and his men.

Gehlen then set up a dummy corporation, called the South German Industrial Development Organisation, as cover for his group’s activities. His deal with the Americans was that he would carry on working for them as Gehlen Org, but that his organisation would revert to the German state once that was re-established. When the General Agreement of 1955 recognised the Federal German Republic (i.e., West Germany) as sovereign state, the Gehlen Org became its foreign intelligence agency under the name Bundesnachrichtendienst (literally: federal intelligence service).

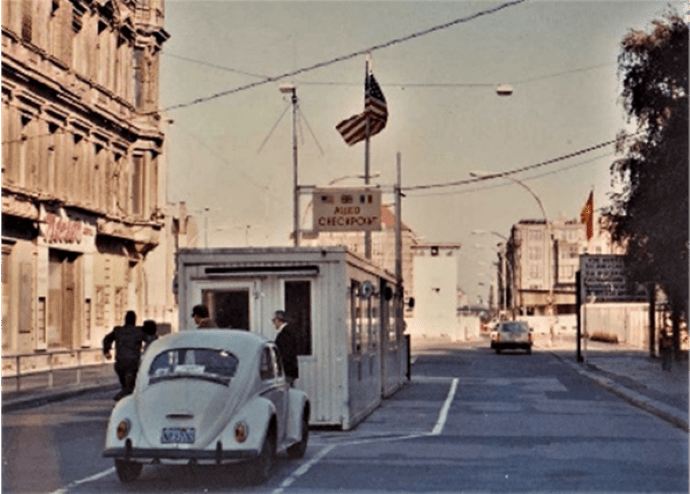

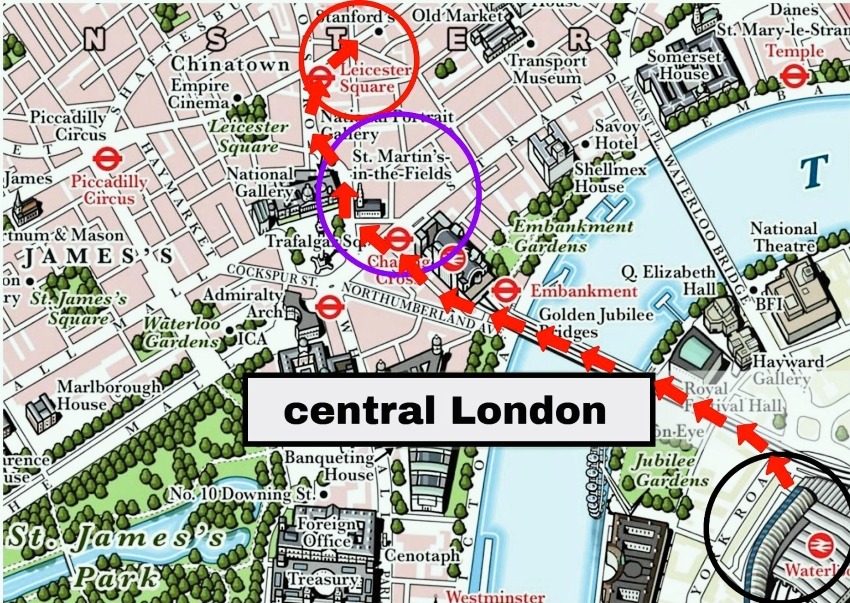

A most revealing and informative part of our visit to Germany was a side trip the BND had organised for our group to West Berlin. We had to fly in on an American plane, keeping to the narrow air corridor that the Soviets had allowed over East German territory (West Berlin was then an isolated enclave deep within communist-controlled land and airspace). Of course, we were taken to the infamous wall, and to Checkpoint Charlie (the crossing point between the American and Russian sectors). Below is a photo that I took there at the checkpoint.