Elands River Siege : 4–16 August 1900

ABSTRACT : The Boer investment in August 1900 of the British Elands River staging post halfway between Rustenburg and Zeerust in the Western Transvaal. The men of the Elands River garrison had had to endure almost two weeks of constant attack from the Boers, spending days in roughly hewn pits, suffering from the heat and thirst and the all-pervading reek of the rotting carcasses of dead animals.

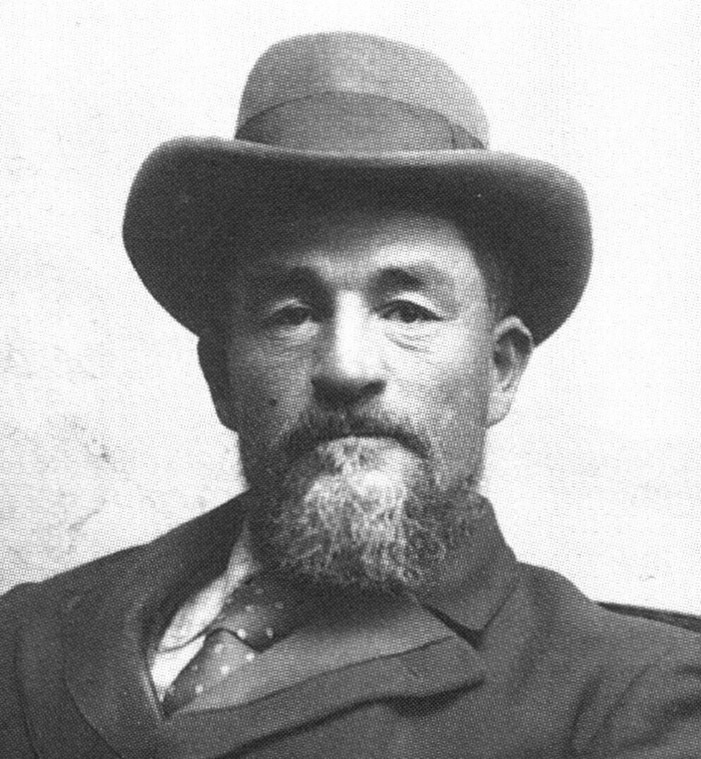

KEYWORDS : Second Boer War, Elands River, Marico District, C.O. Hore, Rhodesia Regiment, British South Africa Police, BSAP, Southern Rhodesia Volunteers, Protectorate Regiment, Robert Baden-Powell, Herbert Plumer, Koos de la Rey, Christiaan de Wet, Frederick Carrington, Frederick Roberts, Kitchener

By August 1900, ten months after the outbreak of hostilities between British forces and those of the Transvaal and Orange Free State Boer republics in South Africa, Her Majesty’s troops were starting to gain the ascendency across the subcontinent in what became known as the Second Boer War.

In the previous December, in what was dubbed the Black Week, the British had suffered nearly 3,000 casualties in a series of defeats at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. The latter was the first of four attempts by General Redvers Buller VC, to relieve the beseiged Ladysmith in northern Natal.

With the arrival in Cape Town of Lord Frederick Roberts VC on 10 January 1900, as supreme commander of British forces in South Africa, and Lord Herbert Kitchener, his Chief of Staff, the tide gradually started to turn in Britain’s favour.

By the end of May 1900, and after the British military disaster at Spioen Kop, Roberts embarked on his “great flank march” to take Bloemfontein, capital of the Orange Free State. Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking were relieved, and Pretoria and Johannesburg taken.

Around Pretoria was harboured Roberts’s army, consisting of a mounted infantry division of eight corps, two infantry divisions, two unattached infantry brigades, four cavalry brigades and four companies of Imperial Yeomanry.

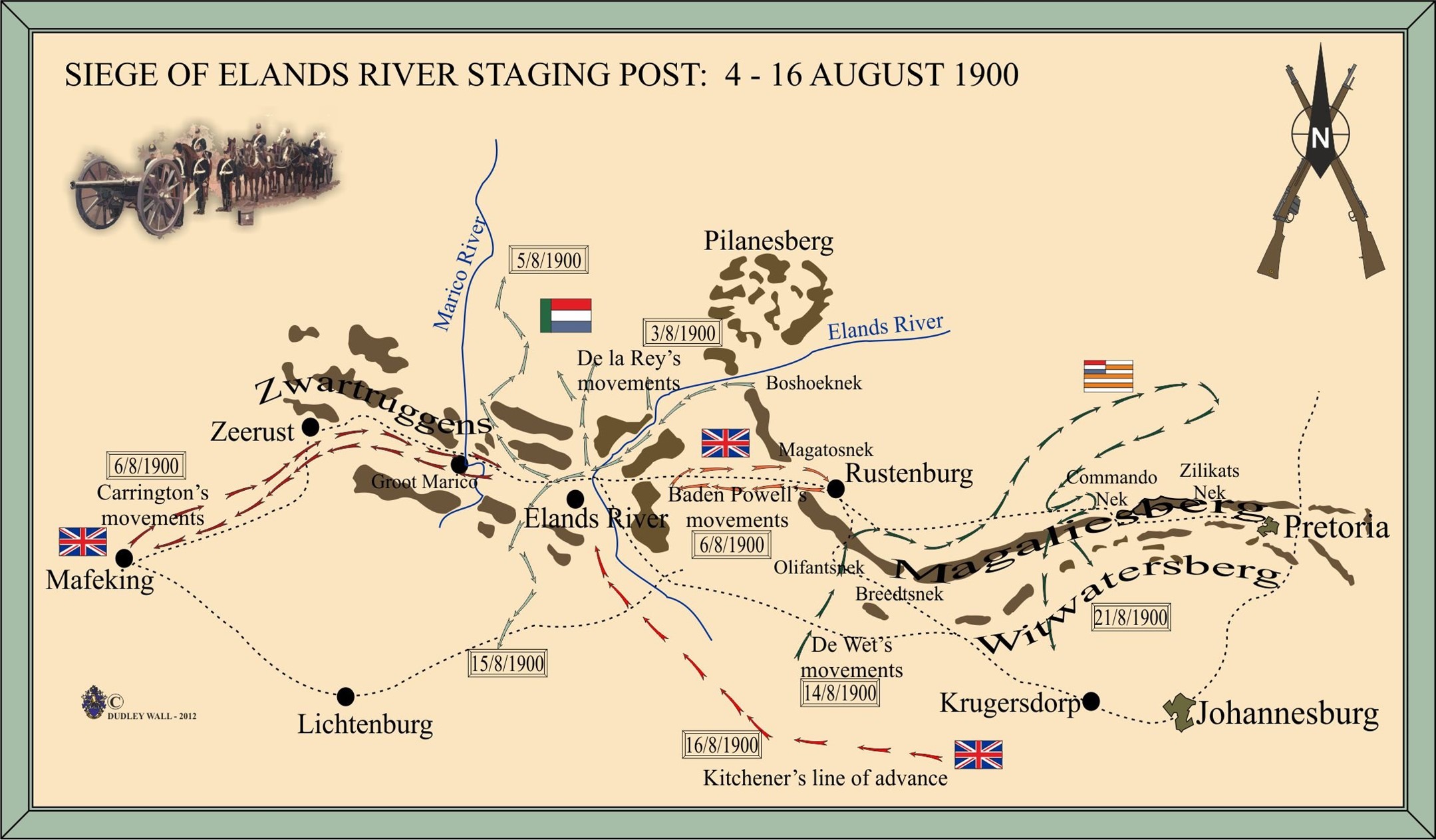

However, in the northwest of the region there were no British troops. One of only a small handful of British officers in the area, the aging Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Carrington was placed on the staff of the South Africa Field Force and given command of the Rhodesian Field Force. But on his arrival from England, Carrington discovered that his field force had been severely depleted of manpower by Colonels Robert Baden-Powell and Herbert Plumer for operations in the Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana) and along the Limpopo River frontier between the Transvaal and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

Following an urgent appeal to the War Office, extra troops were recruited to bring Carrington’s strength up to 4,000. These included the 17th and 18th Imperial Yeomanry, volunteers from Ireland and some of the English counties, and volunteers from Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania, paid for by the British government, and with exotic sobriquets such as ‘Bushmen’ and ‘Rough Riders’. The force was equipped with ten 15-pounder, quick-firing guns and eight Vickers-Maxim machine guns.

Roberts now divided the Western Transvaal operational theatre into districts, with the sole objective of mopping up pockets of Boer resistance. The Marico District, including the towns of Mafeking, Zeerust, Lichtenburg and Rustenburg, was assigned to Colonel Baden-Powell, his force comprising 1,100 Rhodesian Volunteers and British South Africa Police (BSAP).

All the while, British forces continued in their efforts to net the elusive Boer generals Koos de la Rey and Christiaan de Wet, who continued to believe that victory might still be within the grasp of their respective republics. The latter had been pursued across South Africa from the eastern Orange Free State to the Magaliesberg mountains in the north-western Transvaal, where he successfully evaded capture.

With pockets of die-hard ‘bitter einder’ commandos scattered throughout the region, especially in the Magaliesberg, Baden-Powell deployed two mobile columns to effectively search out and neutralise these Boer units. One of these columns, the northern one, was under Colonel Plumer, with a force of 500 mounted men of the Rhodesia Regiment, equipped with four guns of the Royal Canadian Artillery. A small reserve of 100 mounted men of the BSAP was split between the two columns. In addition to this, each of 200 dismounted troops from the Rhodesia and Protectorate Regiments were held at Mafeking and Zeerust.

With the objective of occupying Rustenburg, Plumer’s column move eastwards from Zeerust via Magatosnek in the rugged Magaliesberg mountains. This extensive range of mountains provided a substantial barrier, but several passes, referred to locally as ‘neks,’ allowed access to columns of troops with field guns.

En route, Plumer left a garrison of 100 men of the Southern Rhodesian Volunteers at the drift through the Elands River. Large supplies of provisions and ammunition destined for Rustenburg and brought up by waggon from Mafeking and Zeerust would be secured at this staging post.

Baden-Powell, in the meantime, had moved closer to Pretoria, occupying the Zilikats and Commando Neks to the west of the Transvaal capital. at Rustenburg he left behind a squadron of the Protectorate Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel C.O. Hore, but a few days later, Hore was ordered to retreat down the road towards Zeerust and the staging post at Elands River, as reports were being received of a large force of Boers descending on the town.

Carrington, in response to a requirement to bolster troop strengths in the region, had reached Mafeking on 27 July, but he was told not to proceed any farther east than Elands River, in anticipation of Rustenburg being evacuated in the face of large numbers of Boers under de la Rey, de Wet and Lemmer.

The Elands River camp on Brakfontein Farm in the shadows of the Swartruggens Mountains, once just a communications post between Mafeking and Rustenburg, had by now become a rustic fortified stronghold under the command of Colonel Hore.

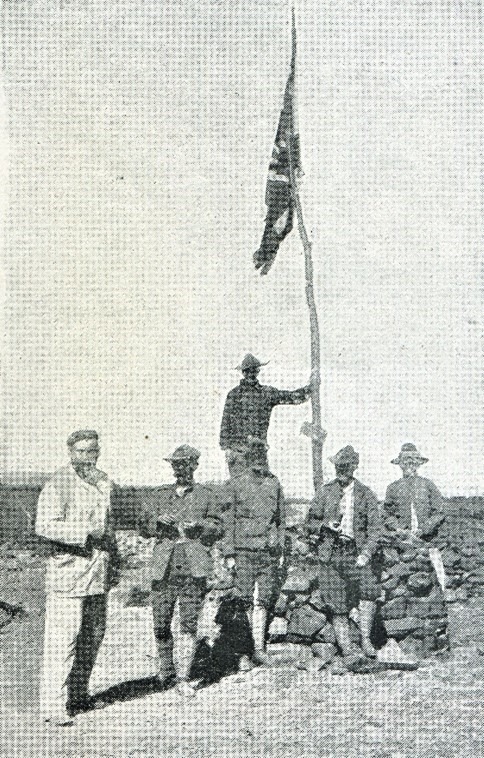

His force, made up entirely of colonials, comprised 105 men of the New South Wales Bushmen, 141 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry, 53 Mounted Infantry from other Australian states, 201 Rhodesian volunteers and BSAP troopers under Captain Sandy Butters, and 50 African drivers. Significantly outnumbered, surrounded by high kopjes and mountains, and with only one 7-pounder gun and two maxims to supplement their small arms, the garrison dug in, hoisted the Union Jack, and prepared themselves to defend the accumulation of stores and ammunition for which they were responsible. English writer Arthur Conan-Doyle would describe their actions over the next fortnight as the “finest resistance of the war.”

On 3 August, Carrington, with a column of 1,100 colonial volunteers and irregulars, had reached the Marico River, where he left 350 men with the 50 waggons needed to uplift the stores and ammunition at Elands River. He believed his progress would be more swift without the lumbering ox-waggons, plus he would replenish his own supplies when he arrived at Hore’s camp. Two days later, and a mere eight miles from Elands River, Carrington parked up the mule transport and continued east with 650 men.

As the column neared their objective, Carrington became concerned that the superior numbers of the Lichtenburg and Marico Boer commandos would not only hinder his passage, but that attempting to cross the last two or three miles over open ground would prove to be disastrous. After deploying two small patrols to find their way to Hore’s camp, only to have them taken prisoner, Carrington withdrew. As he retired, he felt that the only safe position would be Mafeking, resulting in his decision to recover all his troops from Groot Marico and Zeerust.

The post at Elands River was left to its own fate, but Hore and his men were not to know that they had been left on their own to hold the position. This was to prove historically unique, as there were no Imperial armies anywhere nearby, with the consequence that Rhodesians would fight for Rhodesians and Australians for Australians.

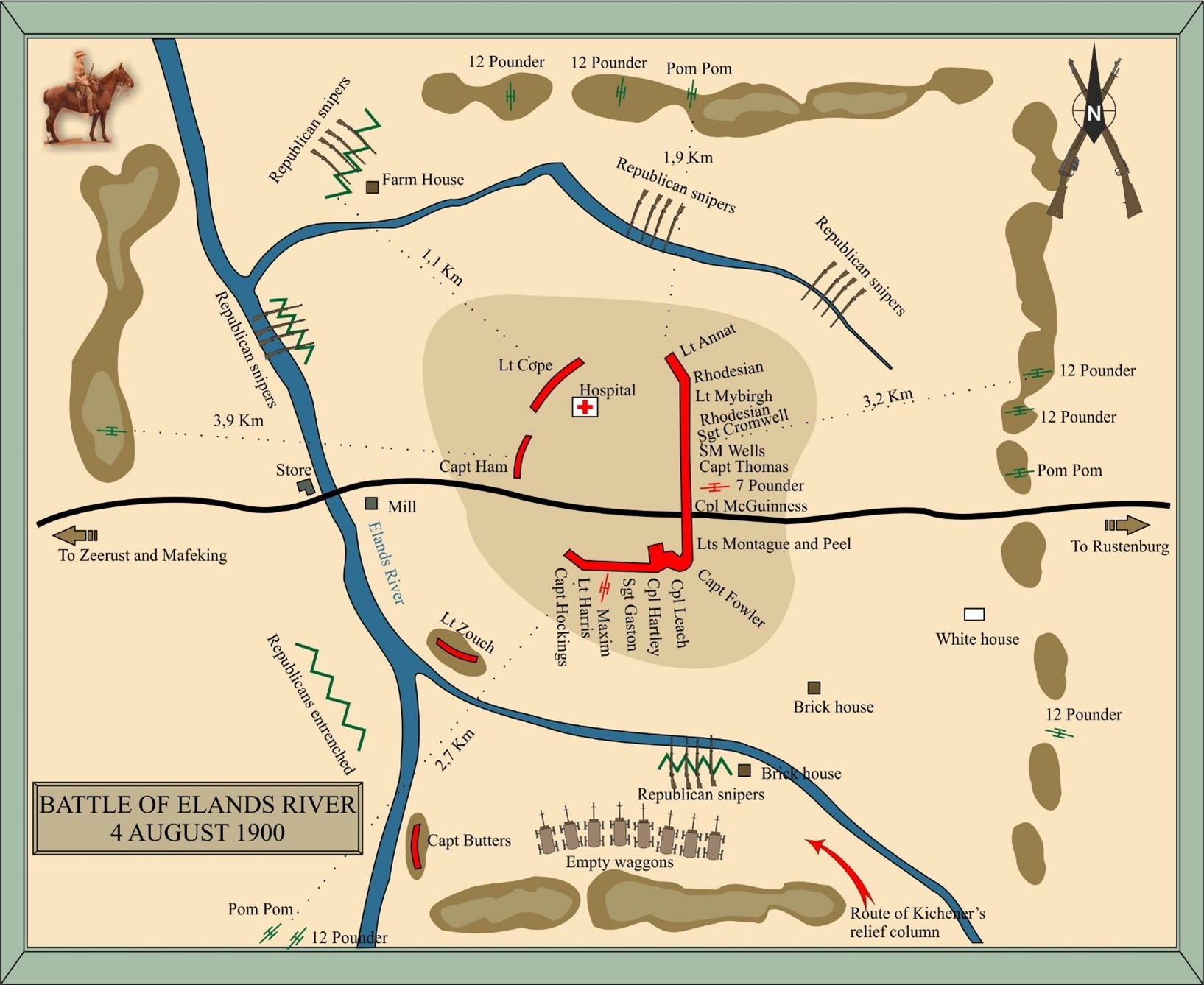

At breakfast on 4 August, the siege commenced as the first Boer artillery shell destroyed the camp telegraph. This was followed by barrage of artillery and rifle fire from the surrounding Boers, a force of 2,000. From kopjes to the west and east, 7- and 12-pounder guns and 1-pounder quick-firing pom-pom guns opened fire on the the post, ranging from 3,000 to 4,000 metres. The Boer guns to the north were much closer, bombarding the hapless colonials, and in the process killing 1,379 of the 1,540 draft animals and horses in the camp. Boer snipers had entrenched themselves in the dry creeks to the north and south, and on either side of the Elands River to the west where it cut the Zeerust to Rustenburg road.

On the first day of the prolonged Boer artillery onslaught, some 1,500 shells landed within the confines of the 12-acre camp, the hospital taking several hits. Five were killed and 32 wounded on that day.

On 6 August, Baden-Powell attempted a rescue bid, but when erroneously hearing that Hore had surrendered, and while still 20 miles from Elands River, he turned around and retired to Rustenburg where preparations were well in hand to evacuate the town and fall back to Pretoria.

Lord Roberts made the decision to withdraw not only Baden-Powell, but also the forces of colonels E.O.F. Hamilton and R.G. Kekewich, the latter from the garrison at Olifants Nek.

After destroying 400,000 rounds of ammunition, Baden-Powell joined the other commanders, leaving the area between Mafeking and Commando Nek totally void of any resistance to the Boer forces under de la Rey. All that remained was the beleaguered garrison at Elands River.

The wily Free Stater, General Christiaan de Wet, seized the opportunity to not only join forces with de la Rey, but also to slip under Lord Methuen’s forces who were desperately trying to corner him. This bold move by de Wet, facilitated by Lord Roberts withdrawing all British forces west of Commando Nek, further exacerbated the situation at Elands River.

On 8 August, de la Rey sent a message to Hore, stating that he had driven back Carrington and suggesting the garrison surrenders. In reciprocal gentlemanly fashion, Hore declined, but asked that the Boers desist from shelling the hospital. The request was complied with, but fighting continued while Roberts mobilised his battalions to ensnare de Wet in the Magaliesberg.

Only by the 13th was news received that Hore had been bravely holding out at Elands River, despite round the clock bombardment. Contrary to prevailing talk, Elands River had not been overrun.

The Boers then commenced attacking at night, with the objective of cutting off the garrison’s water supply. The fortified camp safeguarding the war matériel was in fact about half a mile from the Elands River itself, their only source of water. Such forays by the Boers were repulsed by a small party of Southern Rhodesia Volunteers under Captain Butters, operating from a kopje to the southwest of the camp. A small detachment of Australian Bushmen under Lieutenant Zouch was similarly deployed on an adjacent kopje overlooking one of the creeks. Such defences, however, came at a price.

A native messenger had been despatched by Hore on 10 August to seek immediate assistance. By this time, De la Rey had withdrawn some of his investing forces in order to occupy Rustenburg and Olifants Nek, left vacant by Roberts’s troop recall. Shelling had consequently eased, with the relaxation of the cordon allowing the messenger to break through the Boer lines, reaching Carrington on 13 August. There was at last reaction from Roberts, who instructed Carrington to re-occupy Zeerust and assist with the relief of Elands River. Carrington’s force had been refitted and rested at Mafeking, and had been increased with the arrival of extra troops from the north.

Now fully committed to succour the post, Roberts diverted his resources away from the pursuit of De Wet, ordering Methuen’s division, the nearest force, to move to Elands River at maximum speed. Lord Kitchener had, however, already started before the order was received.

Taking with him two cavalry brigades, Ridley’s Mounted Infantry and Smith-Dorrien’s battalions, Kitchener left at 2.00 a.m. on 15 August, and, after a rapid march of 35 miles, rode into the Elands River camp the following morning with a force of 10,000 men. Spearheading the column, Brigadier R.G. Broadwood’s cavalry had ensured the road was clear on the 14th, followed by Major General A. FitzR. Hart’s force.

While Kitchener was engaged at Elands River, Methuen, the senior officer in the Magaliesberg, continued the pursuit of de Wet. Carrington, with almost 3,000 men, had reached Otto’s Hoop, only half way to Zeerust from Mafeking, and still a considerable distance from Elands River.

De Wet remained impossible to corner. It would ultimately take considerable persuasion by a very tired De la Rey for De Wet to accept British peace proposals, which did not include independence for the republics. His ‘bitter-end’ had come.

The men of the Elands River garrison had had to endure almost two weeks of constant attack from the Boers, spending days in roughly hewn pits, suffering from the heat and thirst and the all-pervading reek of the rotting carcasses of dead animals. Four Rhodesian Regiment troops were killed, the Rhodesian Volunteers lost two, and a further two BSAP troopers perished during the siege. The Australians lost seven, while seven native porters were also killed. There were 58 wounded.

History continues in its attempts to vindicate the decisions and actions of some of Roberts’s senior officers in the first half of August 1900. In July 1899, Baden-Powell had been sent to Rhodesia to raise two regiments, namely the Rhodesian under Colonel Plumer, and the so-called Protectorate under Colonel Hore. Baden-Powell took the Protectorate Regiment with him to Mafeking, where Hore was to gain considerable experience in the handling of siege conditions. Little did he know what else lay in his future.

Plumer would go on to protect the Tuli area of Rhodesia, with the Rhodesia Regiment and elements of the BSAP. He would go on to become one of the greatest British generals of the World War One

Carrington only appeared later, having crossed Rhodesia after landing at Beira, commanding a brigade of Australian Bushmen. He therefore entered the Transvaal from its northwest border. It is argued that the forces at his disposal were significantly diminished by the fact that he was compelled to split the Rhodesian Field Force to reinforce Baden-Powell and Plumer. He however still had a force of 1,000 and a supporting battery of 15-pounder guns, enough for a determined push through to Rustenburg, clearing the Elands River staging post at the same time.

After a minor skirmish and some reconnaissance, Carrington turned back, but not only to the Marico or Zeerust, but all the way to Mafeking. Some of his officers and men noted the incredible speed with which 17 miles were covered that night by the retiring troops. Carrington returned to England at the end of the year.

Baden-Powell, having heard cannon fire in the direction of Elands River as he was making his way towards the post, concluded that either Hore had been overrun, or that Carrington had relieved the siege. He therefore returned to Rustenburg. A lack of supplies at Rustenburg prevented Baden-Powell from committing his force to a further attempt to assess the situation at Elands River.

Boer General Jan Smuts said of the defenders of Elands River, “Never in the course of this war did a besieged force endure worse sufferings, but they stood their ground with magnificent courage. All honour to these heroes who in the hour of trial rose nobly to the occasion.”

Of the defenders of the post, Rhodesian commander Captain Sandy Butters was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, while Corporal Robert Davenport and troopers Thomas Borlaise and William Hunt received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.