ABSTRACT: Revealing article by John Fullerton in NOW! magazine, October 1979, about the “quiet coup d’etat against PM John Vorster in 1978, which Fullerton attributes to a group of generals in the South African Defence Force, stemming from an inter-departmental power struggle between the SADF and the intelligence service / security police.

FOCUS KEYWORD: “Quiet Coup d ’Etat” against PM John Vorster

KEYWORDS: South African political history; John Vorster; P.W. Botha; Dr Connie Mulder; Magnus Malan; Pik Botha; Hendrik van den Bergh; Dr Eschel Rhoodie; BfSS; SADF; South African Police

AUTHOR: John Fullerton, NOW! Magazine 05/10/1979

THE "QUIET COUP d'éTAT" AGAINST PM JOHN VORSTER

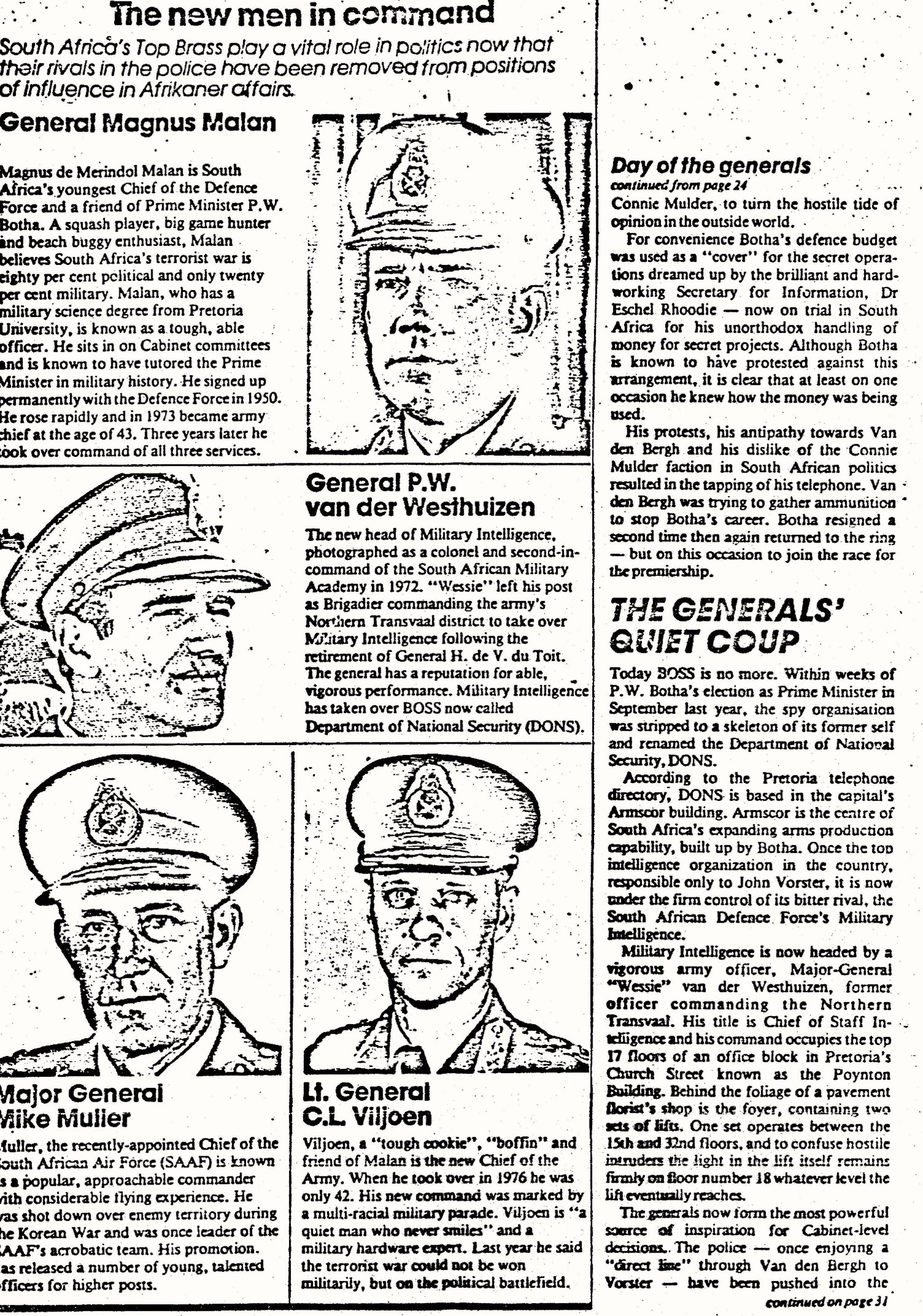

On October 5, 1979, the news magazine NOW! published what it called a documentary article under the title “SOUTH AFRICA: DAY OF THE GENERALS” written by John Fullerton. This nine page long “documentary” was clearly briefed to Fullerton by the SADF (the then SA Defence Force). Among other things, it was lavishly illustrated with studio photos of five senior generals, with fulsome praise for them.

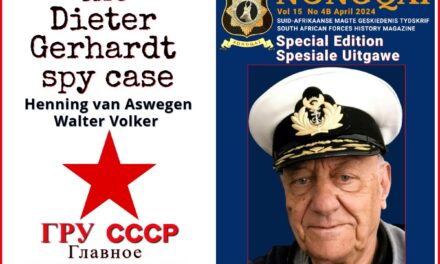

A copy of this article was retained by my father, Frans Steenkamp, then a senior officer of the Special Branch of the SA Police (he was soon to command the SAP-SB as himself a Major-general). My dad left me this copy, among a number of other valuable documents such as the original case docket of the Van Buuren murder trial in which he had been the investigative officer, as well as the Dieter Gerhardt high treason case.

Reading John Fullerton’s article, it is clear that my father kept it because of how revealing it was about the under-handed power play that a certain “cabal” in the military (as other officers were later to refer to them) had initiated to oust prime minister John Vorster in what was called “a quiet coup d’etat”. Even more revealing, is the sense of dominant political power that this element in the Military subsequently believed itself wielding, with the article stating that: “…the South African generals are now in a position of power, unrivalled in the so-called free world.”

John Vorster and his team (such as dr Connie Mulder, dr Eschel Rhoodie, and general “lang Hendrik” van den Bergh) have been vilified and to all intents and purposes obliterated from Afrikaner history. This, despite the undeniable historic reality that the PW Botha regime that had ousted Vorster ended in ignominy. Its securocrat-driven policies of choosing to shoot rather than settle (as Vorster had aimed to do) resulted in total failure. It left the country isolated, on the brink of war and of a destructive confrontation not only with the Third World, but also with the West.

Such was the strategic failure that it left Botha’s successor, FW de Klerk, with no other option than to revert to Vorster’s policies of seeking a negotiated settlement – but then, with precious few cards left in hand, after the “lost decade” under Botha and his preferred group of generals.

Because the article by Fullerton is so revealing, we are placing it in virtually its entirety so that you can judge for yourself.

"DAY OF THE GENERALS"

The tapping of Pieter Botha’s phone in 1977 lit a fuse that led to Muldergate and the defeat of BOSS. John Fullerton traces the conflict which ended in a quiet coup d’etat by the military.

BATTLE OF THE SPIES

One scorching summer day in early 1977 Pieter Willem Botha, South Africa’s Minister of Defence and future Prime Minister, received a report which would change the course of history in southern Africa.

The message was nothing more, nor less, than a personal declaration of war. It simply informed the Minister – then the third most important man in Prime Minister John Vorster’s Cabinet – that his counter-intelligence staff had found that Botha’s own telephone was tapped.

The culprits were not the Soviet KGB, the American CIA or the Cuban Dirección General de Inteligencia. That would have been a fairly routine matter to tackle. It was far worse. The responsible organisation was a rival South African intelligence organisation – the much-publicised but little known Bureau of State Security, BOSS.

The tapping of P.W. Botha’s telephone lit a fuse which would eventually lead to the Muldergate scandal – an explosive mixture of corruption and high-level incompetence which in turn paved the way for a quiet coup d’etat by South Africa’s generals and Botha’s succession as Prime Minister. The hitherto unrealised effect of the incident has been to put South African policy-making under the direct control of the military, with immense consequences in the future fr the people of South Africa. It led to the demise of BOSS, the ruins of which have also been taken over by the military. As a result the South African generals are now in a position of power, unrivalled in the so-called free world.

And all this came about as a result of the unchecked power of the police – symbolised by the tapping of P.W. Botha’s telephone little more than two years ago. In those days BOSS was one of the most powerful, and feared, security organisations in the world. Established in 1969 by Act of Parliament as a high-level co-ordinating agency for the security services, it was in effect an executive extension of the Prime Minister’s personal power.

The Bureau operated world-wide. It was responsible to Vorster’s own department. It was run by the Prime Minster’s closest friend and adviser, the 6ft 5in policeman, General Hendrik van den Bergh.

When Botha learned that Van den Bergh was responsible for the surveillance of his office, the Defence Minister reacted instantaneously. He lost his temper, stormed into Vorster’s office and resigned. But he came back. He did so because his generals urged him to do so, believing that his special vision of South Africa’s future was too important to lose.

The bug on his telephone line was of great significance. It told Botha he could expect little quarter from his powerful adversaries.

Van den Bergh, the policeman, and P.W. Botha, the politician, detested each other. Van den Bergh came from the hardline or verkrampte Transvaal, Botha from the traditionally liberal or verligte Cape. Botha was considered an outsider by the general. “We will keep the Cape foreigner (Kaapse vreemdeling” out, Van den Bergh boasted more than once.

Together with his later mentor, John Vorster, Van den Bergh had been a member of an ultra-right organisation, Ossewa Brandwag in World War Two. For their sins they were interned together at Koffiefontein camp, along with many other pro-German Afrikaners.

After the war, Van den Bergh joined the South African police as a constable. He spent some years in obscurity, then, with Vorster’s help, began to rise rapidly. When Vorster finally overcame his politically debilitating extremist background and became Minister of Justice, Police and Prisons (nicknamed “The Hangman”), Van den Bergh became a full colonel and took over the police political wing, the Special Branch.

That was when trouble really began . The ambitious Van den Bergh turned the Special Branch into a private empire, a separate organisation responsible to Vorster, who was to become Prime Minster in 1966 following the assassination of Verwoerd.

Van den Bergh built his reputation on the suppression of illegal opposition groups – such as Poqo and Spear of the Nation – the arrest of John Harris who planted a bomb in Johannesburg railway station, and the capture of Afrikaner communist and fugitive, Bram Fischer.

Botha had ample cause to dislike the policeman who had been a thorn in his flesh for years. Increasingly, Van den Bergh’s policemen were challenging the military for political influence at the top table. An example of this came over the penetration of the underground African Resistance Movement by Botha’s Military Intelligence. Van den Bergh was to complain later that the military had failed in their duty to inform his Special Branch of ARM’s existence. Had this happened, he said, ARM could have been crushed years earlier and acts of sabotage prevented.

As head of the newly created BOSS, Van den Bergh, now a general had been appointed Secretary for State Intelligence. In this position he dominated security and intelligence work because his new post put him at the head of the State Security Committee. The committee was designed to coordinate intelligence operations, but in fact it never really functioned. Van den Bergh was vain and a publicist. He liked to use “psychology” in personally interrogating his political prisoners. Like Vorster (who used to pay detainees visits in their cells to try and understand what made them “tick”) Van den Bergh seemed to be fascinated by his victims. But unlike some of his police colleagues, he did not personally use violence to extort confessions.

The closest he seems to have come to that was when he was a police lieutenant in the arid northern Cape. He fed a suspect a delicacy of salted fish known locally as snoek. When the man asked for water Van den Bergh told him he could have all he wanted to drink once he had made a confession.

But Van den Bergh’s rapid rise to notoriety alienated his police colleagues. His exhibitionism obscured any real achievement. And his arrogance and love of the good life would provide his military rivals with sources of information on his activities in later years.

Right from the start BOSS took charge of all covert operations. It si said that one Monday morning Van den Bergh and his side-kick, General Mike Geldenhuys (former head of the Secial Branch and now Commissioner of Police) simply walked into Military Intelligence headquarters and physically occupied the premises, to the consternation and fury of the military.

Several senior Military Intelligence officers were reportedly dismissed by Van den Bergh – and one or two of these were later re-employed on the BOSS pay-roll. It was a case of “divide and rule”.

According to one informed source when Van den Bergh moved into Military Intelligence headquarters he failed to take an elementary precaution. The military had left a parting gift – electronic listening devices in the general’s new territory. From them they soon learned that Van den Bergh discussed members oof the Cabinet in plainly derogatory terms and had quickly begun to build up files on the personal lives of a number of influential and respected South African leaders.

That was when P.W. Botha first resigned in protest, having fulminated vainly to Vorster about Van den Bergh’s excesses, as he was to do about the phone-tapping incident almost eight years later. Botha was back in office within a week. His resignation was typical of the man – temperamental, and inclined to fly into a rage.

But the policeman’s slap in the military’s face would not be forgotten or forgiven.

The South African Defence Force – in particular, Military Intelligence – provided assistance to forces in the Nigerian Civil War and Van den Bergh later claimed that the first he ever heard of it was when the CIA told him of South Africa’s involvement. P.W. Botha was hitting back.

In 1975 Botha’s forces moved into Angola in the wake of Portugal’s withdrawal from Africa. South African involvement had initially been hesitant, slow, and involved merely arms supplies to movements opposing the new Marxist authorities in Luanda. Then when the recipients failed to use the weapons effectively, South African military instructors went in. Secrecy shrouded the operation until Defence Minister Botha presented the incursion by South African armoured columns as a fait accompli to the Cabinet.

Van den Bergh was outraged. He considered the whole affair a major blunder a threat to the détente he and the Minister of Information, C.P. “Connie” Mulder, were secretly constructing.

Flor their part, the military objected to Van den Bergh’s influence in restraining Vorster from moving rapidly into Angola in greater strength. The Defence Force spokesmen maintained that if their soldiers had been allowed greater freedom of movement, Luanda would have fallen to South Africa.

Van den Bergh did not stop there. The Defence Force had allegedly prepared a small column of military vehicles for a lightning strike into Mozambique, to link up with Portuguese colonists opposed to the Maputo regime of Samora Machel.

Van den Bergh boasted that his agents succeeded in delaying the invasion by sabotaging the vehicles at Komatipoort on the Mozambique border sufficiently long for Vorster to be informed and Botha brought to heel.

In another incident, the head of BOSS accused Botha of challenging the South African Police’s paramilitary ambitions in Rhodesia. Botha was accused by Van den Bergh of putting several hundred paratroopers on standby for possible commitment to Rhodesia’s guerrilla war.

While BOSS was above all an external intelligence-gathering organisation, Van den Bergh was also using his new command to operate inside South Africa – at Prime Minister Vorster’s instigation. The first target was a group of right-wing Afrikaner dissidents, some f whom had broken away from the sacrosanct National Party. BOSS collected information on individuals by intercepting mail, bugging telephones and infiltrating the ultra-right Herstigte Nasionale Party. The information was then used in smear campaigns and circulated within the ranks of the 12,000 strong Afrikaner Broederbond. Rightist elements were effectively discredited – so much so that some 200 Afrikaners are reported to have been purged from the secret society.

A leading South African academic told NOW! that BOSS was responsible for creating opposition to the articulate and charismatic homeland leader, Gatsha Buthelezi. A statesman-like head of te Zulu nation, he is well known in Western capitals for his vehement opposition to apartheid.

“BOSS was sophisticated in its approach” said one source. “It must have known it couldn’t stop Buthelezi, but at least kit would give him something to think about and show the outside world that he did not have the complete support of his people.”

In the early 1970’s there were press reports of three occasions on which people were apprehended by the police for posing as Special Branch officers when in fact they were from BOSS. Van den Bergh was riding roughshod across the territory oof other government agencies. He was, with Vorster’s support, supremely confident.

There seemed to be no limit to Van den Bergh’s ambition. He now set out to liaise with the Minister of Information and leader of the National Party in the Transvaal, Connie Mulder, to turn the hostile tide of opinion in te outside world.

For convenience Botha’s defence budget was used as a “cover” for the secret operations dreamed up by the brilliant and hard-working Secretary for Information, Dr Eschel Rhoodie – now on trial in South Africa for his unorthodox handling of money for secret projects. Although Botha is known to have protested against this arrangement, it is clear that at least on one occasion he knew the money was being used.

His protests, his antipathy towards Van den Bergh and his dislike of the Connie Mulder faction in South African politics resulted in the tapping of his telephone. Van den Bergh was trying to gather ammunition to stop Botha’s career. Botha resigned a second time then again returned to the ring – but on tis occasion to join the race for the premiership.

THE GENERALS’ QUIET COUP

Today BOSS is no more. Within weeks of P.W. Botha’s election as Prime Minister in September last year, the spy organisation was stripped to a skeleton of its former self and renamed the Department f National Security, DONS…

Once the top intelligence organisation in the country, responsible only to John Vorster, it is now under the firm control of its bitter rival, the South African Defence Force’s Military Intelligence…

The generals now form the most powerful source of inspiration for Cabinet-level decisions. The police – once enjoying a “direct line” through Van den Bergh to Vorster – have been pushed into the shadows. The Defence Force plays a prominent role on most areas of policy – an influence encouraged by the military’s champion, P.W. Botha.

Malicious gossip aimed at Botha occasionally centres on the fact that he failed to complete his university course as a young man (although he now has an honorary degree in military science from Stellenbosch University). In fact, Botha is no intellectual, but he has certainly proved to be an excellent student of World War Two.

His tutor is General Magnus Malan, the young Defence Force chief. Malan used to prepare reading lists for Botha who would go to the library, pick up an armful of volumes on military history, read them and return for the next batch. One lesson he is said to have learnt well is the damage to the Nazi war effort created by deep divisions between the rival intelligence organisations, the Abwehr of Admiral Canaris and Himmler’s Sicherheitsdienst…

South Africa’s generals want, it appears, to know everything about government. A senior commerce official complained to a Western diplomat recently that he had to waste too much time teaching the intricacies of exchange control regulations “to the generals”.

Another example of the political role of the generals occurred over a government survey into the impact of apartheid in an area of Capetown’s District Six, a suburb for the city’s Coloured (mixed-race) community, which has in recent years been turned over to whites. According to one source, the investigation is being carried out by Military Intelligence.

If further confirmation were required it came last August when the man observed arriving late for a Cabinet committee meeting on the subject of black homeland consolidation was none other than General Magnus de Merindol Malan.

It is General Malan who sits at Mr Botha’s side during the negotiations with the Western Big Five over the future of South West Africa/Namibia. And it is Malan who joins Botha in meeting the world’s press.

The reason for the military’s presence is clear. Over the past 15 years the threat to Afrikaner power has changed from one of internal subversion to externally-based “liberation movements”, stemming from the creation of independent black states a few hours drive from Pretoria. Secondly, the psot-war years were marked by English-language domination of the armed forces. Under a Nationalist Government and with the assistance of the Broederbond, which sets out to “Afrikanerise” South Africa, Afrikaners climbed speedily up the promotional ladder and the Defence Force “came in from the cold”.

Finally, South Africa has changed. Material plenty, economic expansion, the high price of gold and increasing Afrikaner intervention in commerce has created a pool of new para-state organisations, such as the oil-from-coal giant Iscor (sic). These “empires within empires” have fragmented traditional controls, disturbed old loyalties and provided a racially reformist military with the opportunity to take over the driving seat.

FALL OF THE CROWN PRINCE

The scandal known as “Muldergate” was a symptom of change at its worst in the Afrikaner volk. It destroyed several reputations, put P.W. Botha in power and gave the military its political might…

Vorster was by that time an ill man. He had always suffered from low blood pressure and had difficulty sleeping. His fear of a split in Afrikaner ranks added to his habit of prevarication in the face of crisis. He allowed his Cabinet colleagues to manoeuvre unchecked. He would never censure people because he would never, if he could help it, go down in the history books as the man who divided the National Party leadership…

His new protégé was the charismatic Foreign Minister and the man the general public favoured as the next Prime Minister.

Pik was an enlightened or verligte politician and a newcomer to power politics, for he had spent several years abroad. He lacked a provincial power base. He had to play a waiting game and discover all he could about the scandal before it became common knowledge…

Pik formed an objective alliance, as Marxists would say, with his namesake – objective because Pik had personal ambitions which would not include anyone else, not even P.W. Botha. The two minsters decided to force the Muldergate issue into the open before the premiership election in September last year and in meeting with Vorster on the eve of the traditionally secret ballot held to choose a new leader, a confrontation took place.

On September 28, 1979, P.W. Botha was elected Prime Minister. In the final round of elimination voting Pik had given P.W. Botha his minority vote; this effectively split the big Transvaal group and shut Mulder out of the race.

Sources close to Mulder bitterly maintain that “Muldergate” was deliberately used to bring P.W. Botha to power as an interim solution until such time as Pik could gather his forces. This is an oversimplification, but for Mulder himself the National Party has been “hijacked” by men who destroyed South Africa’s détente and risked bringing down the Nationalist oligarchy purely out of personal ambition…

WILL BOTHA SURVIVE?

P.W. Botha certainly has the support of his generals, upon whom he is so dependent. Under his leadership the defence budget doubled between 1971 and 1973, went up 43% in 1974, 36% in 1975 and 42 per cent in 1976. By 1977 it took up one-sixth of the total government expenditure…

As he is a man for whom military security is all important, his quick temper, his reliance on the generals could combine with a foreign crisis – in Namibia or Zimbabwe – to create a major confrontation.

The battle of the spies has put the military in charge of South Africa’s destiny for a long time to come. Whether P.W. Botha survives or not, the generals will have to be reckoned with.” []